History never repeats

New Zealand’s history of drugs and the laws to control them

Just when did people living in the land of the long white cloud begin using drugs? What turned them on? And off? When were the rules changed? Russell Brown surveys the long history of imbibing in Aotearoa New Zealand

New Zealand has a prominent place in many of the global narratives around psychoactive drugs. We have led the world in seeking new ways to curb the use of some – and in our prodigious national appetite for others. We were the world’s keenest consumers of LSD for years and continue to sit near the top of the table for amphetamines, MDMA and cannabis. We were virtually born into binge drinking as a nation.

And it all started from… nothing.

The early days

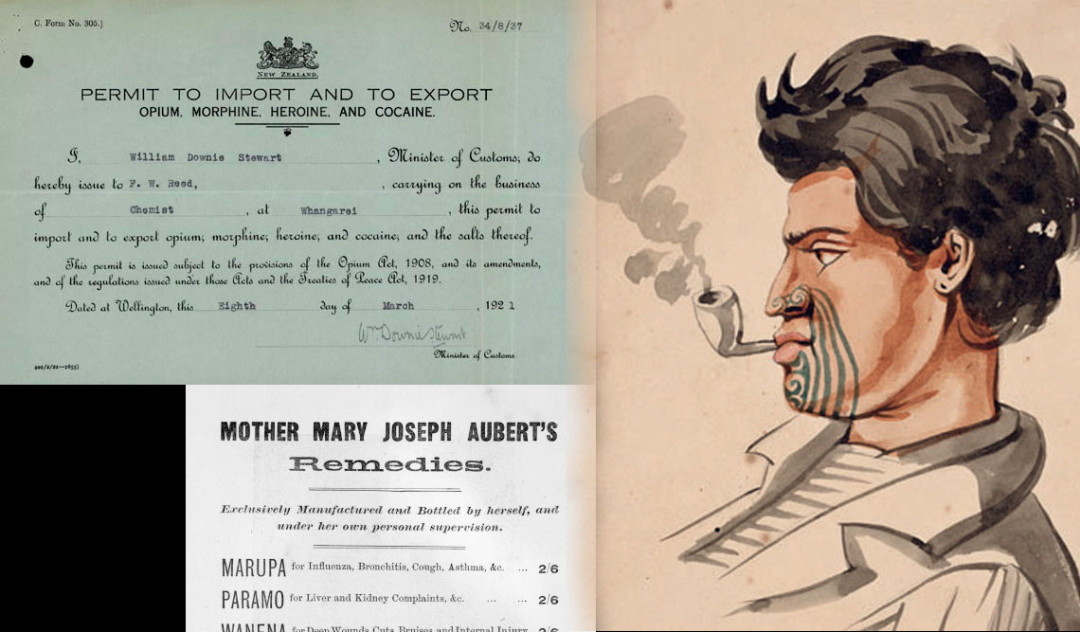

The accepted view is that, before the arrival of Europeans, Māori were one of the few societies that had no intoxicants. This does not necessarily mean they had no use for psychoactive substances.

Kawakawa (a relative of kava), pukatea (containing the analgesic alkaloid pukateine, which has a similar chemical structure to morphine) and radula marginata (a species of liverwort containing the cannabinoid perrottetinene) were all used as rongoā, or traditional Māori medicines. And all can now be purchased from specialist ethnobotanical suppliers and turn up occasionally in reports in the forums of drug experience sites like Bluelight and The Shroomery.

But there’s no evidence these plants were used outside of a medical context by Māori, who were vulnerable when tobacco and alcohol were introduced by European visitors in the late 18th century. While some Māori leaders strongly discouraged the use of both, they soon became currency in trade. A pattern of tobacco use by Māori women took hold in the early 19th century (a time when smoking was frowned upon for European women) and persists to this day.

Heavy alcohol use was characteristic of 19th century settlers, but Māori didn’t catch up until the 1890s. In her Te Ara article ‘Māori smoking, alcohol and drugs – tupeka, waipiro me te tarukino – Māori use of alcohol’, Megan Cook suggests that alcohol “was used to blunt the grief Māori communities experienced as a result of high rates of death and loss of land”.

While a series of alcohol regulations specific to Māori were passed in the 1800s, the colonists themselves had ready access to opium (as laudanum), cannabis and even cocaine. The patent medicine Chlorodyne (which contained morphine, chloroform and cannabis) was popular and even given to children, and it seems likely that the British experience of Chlorodyne addiction and overdose was equally visited on the colonies. Cannabis cigarettes were widely advertised in 19th century newspapers as a cure for asthma and insomnia. In the 1860s, some migrant Chinese miners brought opium smoking to New Zealand.

Seroious attempts at regulation begin

Although some official efforts were made to curb the use of opium, it wasn’t until 1912 and the International Opium Convention (the precursor to the UN Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs) that the trade in opiates and later cannabis was more seriously restricted, ultimately via the Dangerous Drugs Act 1927.

At the same time, a new popular mood was driven by wire stories from the British and American press. In 1911, the Auckland Star billed negotiations over the Opium Convention as a matter of “Checking the Dope Fiend”. A lurid story published in 1919 by the Marlborough Express, on the death of musical actress Billie Carleton reported that, “The dope fiends of London seek only one thing – the feeling of wellbeing, of exhilaration, the elimination of time and space.”

We had our own stories: in 1917, there were reports that “shirkers” were seeking to avoid the call-up for war by taking “dope” so they would fail the medical. And by the 1930s, when the Auckland Star ran a glossary headed ‘Argot of the Dope Fiends’ (“H” for heroin, “Candy” for cocaine and “Happy dust” for “any powdered dope”), New Zealand was very much in line with the international consensus on drugs.

Well, nearly. In ‘Drugs – Restricting drugs, 1866 to 1965’ for Te Ara, Jock Phillips writes:

“Despite these restrictions there was still considerable use of the drugs under prescription for medical purposes. In the late 1940s it was discovered that doctors were prescribing heroin so freely that New Zealand had one of the world’s highest rates of use per person. By 1955 this had been drastically reduced.’

Remarkably, New Zealand also had medical marijuana well into the 20th century. In his book New Zealand Green, Redmer Yska notes that cannabis was prescribed by some doctors for migraine and hypertensive headaches, although “users were mainly in the Auckland district, whereas the Wellington and South Island areas had seldom heard of such prescriptions”.

In 1955, in response to a World Health Organization request, New Zealand agreed to end medical cannabis imports. While a dwindling group of elderly Chinese opium smokers occasionally made the headlines, the use of psychoactive drugs apart from alcohol and tobacco was largely invisible to the wider public from the mid-50s. Which didn’t mean it didn’t happen.

Jailhouse rock

The 50s dancehall and rock ‘n’ roll scene in Auckland and Wellington was fuelled by prescription amphetamines, and while the pubs would continue to close at 6pm until 1967, clubs like The Top 20 in Auckland opened six nights a week in 1962 and rocked until 2am at the weekends. Legendary singer Max Merritt recently explained to the Audioculture website how he and his band managed the hours virtually without breaks – whisky and speed: “Man, by 2am we were bouncing off the walls!”

Marijuana – mostly brought in on merchant ships from the early 1950s, but some of it grown unrecognised in suburban back yards – was more the thing of jazz and literary cliques in Auckland and Wellington. Again, it was largely invisible to the wider public – until Auckland ‘it girl’ Anna Hoffman was charged in 1959 with supplying cannabis to an undercover policeman (“I had no idea it was illegal,” she said many years later in the documentary High Times: The New Zealand Drug Experience). She was sentenced to six months’ jail, and the city was scandalised.

Things were beginning to change, permanently.

The house at 115 Bassett Road, Remuera, was the creation of New Zealand’s liquor laws: an illicit ‘beerhouse’ where people could keep drinking after the pubs closed at six o’clock. It was a criminal offence to run such a place, so criminals did the job, sometimes facilitating the supply of other drugs and sexual services into the bargain. The beerhouses were tacitly tolerated until, in December 1963, the proprietors of the Bassett Road beerhouse, Kevin Speight and George Walker, were found shot full of bullets from machine guns.

If the shootings were the result of competition for the supply of one drug, alcohol – the killers, Ronald Jorgensen and John Gillies, came from a rival beerhouse in Ponsonby – they would also become associated with another, marijuana, when it emerged that Gillies had smoked a “reefer” before setting off to do the job.

The Police publicly took the view that marijuana created homicidal urges. Officer Bob Walton was dispatched in 1964 to learn more from his American contemporaries and, on his return, established New Zealand’s first drug squads and helped draft the extraordinary Narcotics Act 1965, which reversed the onus of proof in drug cases and set a penalty of 14 years’ imprisonment for possession of more than an ounce of pot. (“At the time, the Act was seen as draconian in relation to the problem,” noted the official Police tribute to Walton on his death in 2008.)

If the new Police teams and harsh law were meant to cut off the drug problem before it grew, they failed. In 1967, 10 New Zealand pharmacies and five doctors’ surgeries were burgled in search of drugs. The following year, the Police recorded 118 burglaries or thefts from pharmacies and 37 from surgeries. Between 1966 and 1970, the number of people aged under 25 charged with drug offences jumped from 14 to more than 200.

Growing appetite to get high

What the flurry of enforcement couldn’t do was change demographic reality. The post-war cohort of Baby-Boomers was reshaping society. The more the news media reported in a shocked voice that this or that overseas pop-culture hero was associated with marijuana or LSD, the more they established to the Boomers that drugs were indeed part of popular culture.

LSD appeared locally around 1967, and New Zealand’s per-capita use of the drug was said to be the highest in the world during the two decades that followed. In the same year, in the first issue of Chris Wheeler’s scabrous pamphlet Cock, Dr Erich Geiringer was the first New Zealander to advance the argument that marijuana’s criminal status was in fact more socially harmful than the drug itself.

Ironically, “The Man” became a significant source of drugs for the counterculture. In 1967, 13kg of marijuana was seized in a bust at the headquarters of the US Operation Deep Freeze base at Christchurch Airport. Twenty years later, some of those who protested the visits of American nuclear vessels in Auckland would ruefully acknowledge to each other that they were marching to end their own source of high-quality LSD, which was believed to come in on those same ships.

But just as many drugs were simply walked through airport arrival halls, in the days before sophisticated screening. In 1975, when Marty Johnstone bought a boat called The Brigadoon and had it pick up 450,000 “Buddha sticks” in Thailand, importation hit a grand scale. The Thai cannabis brought in by Johnstone and Terry Clark, in what became known as the “Mr Asia” syndicate, first wrecked the market for the less-potent local pot, then set a new market standard for “New Zealand Green” to reach.

But the greater impact came when Mr Asia turned to a more profitable product: heroin. While punk rock in Britain was largely fuelled by the same drug that had given the mod and northern soul movements their energy – speed – New Zealand’s nascent punk scene went with what was at hand, which, thanks to Johnstone and Clark, was heroin.

The drug took its toll at the time, but its real impact arguably lies in the “silent epidemic” of hepatitis C, which continues to echo decades later. It’s also a grim lesson in the failure of harm reduction.

New Zealand IV drug users could not buy syringes from pharmacies, there would be no safe-use education until the 1990s and needle exchange programmes were decades away. Around 50,000 New Zealanders are thought now to be infected, and three-quarters of them are undiagnosed.

The lack of harm-reduction strategies was not for want of official advice. The Blake-Palmer Committee report in 1973 declared there was “little, if any, chance of halting, let alone reversing, the steady escalation in the misuse of drugs” unless New Zealand was prepared to commit to treatment and education. he report formed the basis of the Misuse of Drugs Act 1975 and in particular the Act’s introduction of three schedules based on the harm attributed to particular drugs, finally separating cannabis from heroin in the eyes of the law.

The extraordinary scale of the Mr Asia organisation meant that it touched the lives of many New Zealanders who went on to become ostensibly respectable citizens – and that it left a significant vacuum when the enterprise was eventually taken down with the arrest of Clark for Johnstone’s murder in 1979.

Backyard chemists and designer mixes

That vacuum quickly saw the reappearance of the same DIY approach to drug manufacture that we saw during the decades of the harshest regulation of alcohol supply. But while it was (unusually, in world terms) never illegal to privately distil or brew liquor in New Zealand, the practice of converting pharmaceutical painkillers into monoacetylmorphine in makeshift home labs was always illicit. That did not stop so-called “homebake heroin” becoming a characteristic (and unique) feature of New Zealand drug culture.

Enforcement also took its toll on the Police, especially after the Police undercover programme was launched in 1974. Bruce Ansley’s 1995 book Stoned on Duty told the story of former undercover policeman Peter Williamson’s descent into addiction and repeated perjury, and the 2008 Gibson Group documentary Undercover: The Thin Blue Lie, recalled many more.

Marijuana, meanwhile, become less a feature of any subculture than part of the national culture itself. Bob Marley’s visit in 1979 manifested the fairly loose interpretation of Rastafarian culture that had been embraced by young Māori and Pasifika New Zealanders, and everyone knew why the pioneering Pacific reggae group Herbs had adopted their name. In 1981, the protagonists in Geoff Murphy’s film Goodbye Pork Pie smoked and enjoyed marijuana furnished by Bruno Lawrence’s philosophising drug dealer. Hardly anyone was scandalised.

In 1990, the University of Auckland’s Alcohol and Public Health Research Unit surveyed 5,000 people in Auckland and the Bay of Plenty and found that 43 percent of people questioned had tried marijuana at some point. A follow-up survey in 1998 found that number had increased to 52 percent.

But even in the second survey, 73 percent of respondents said they thought regularly smoking marijuana posed a “great risk” of harm. And some communities, especially Māori in the regions, had discovered the downside of living and raising children in an environment where cannabis was both a profitable crop and a fact of life. In both of the Alcohol and Public Health Research Unit surveys, there was greater concern about alcohol as a “community problem” than cannabis, but concern about marijuana had grown by 1998 – and was strongest amongst under 25-year-olds. Generation X had become more wary of cannabis than its Baby Boomer parents.

In 1986, a few New Zealanders returning from Sydney brought back news of something called “designer drugs” and possibly even the drugs themselves. In general, the term referred to one drug: MDMA, or ecstasy, which would, in the next few years, become tightly tied to a powerful popular culture movement: modern dance music, via the acid house craze that exploded in Britain in 1988.

When the first house parties came to New Zealand in early 1989, MDMA was already there waiting for them. It was also the favoured drug for a subsequent wave of young New Zealanders who had made their way home from Europe, some through the party scenes of reinvented hippie havens like Goa.

The downers sought out by the users of the 1970s had no place in the new scene, which wanted drugs that let you stay up all night – or even all weekend. A growing subculture developed almost unnoticed by the mainstream media – until Ngaire O’Neill died after taking ecstasy in October 1998.

The 27-year-old Aucklander’s death was not down to taking ecstasy per se but a result of “dry drowning” – she drank herself to death with water. This was a point lost on most of the media and, indeed, on Auckland coroner Mate Frankovich, who declared that she was drinking so much water because the ecstasy had diluted the salt in her blood.

A full-blown moral panic sprang up. The following year was election year, and Prime Minister Jenny Shipley promised to reclassify MDMA, on the basis of a single death, from Class B to Class A, placing it alongside heroin. (Shipley lost the election, but MDMA was eventually moved from Class B1 to B2.)

The media hysteria was boosted further in March 1999 when a young surfer called Jamie Langridge died at a dance party on Pakatoa Island. An autopsy showed Langridge had used not only ecstasy but large quantities of alcohol and speed and had sustained a head injury when he slipped and fell on concrete. But when Police photographed 500 strung-out partygoers as they arrived back from the island the next morning, something else was evident: these people weren’t all kids and ratbags. The party crowd included many professionals and even lawyers.

Methamphetamine in new garb

While all this was going on, something much more troubling was happening. According to the 2005 documentary High Times: The New Zealand Drug Experience, “a prominent Auckland businessman” met with gang representatives in late 1999 to discuss rebooting the market in methamphetamine, which had been present in New Zealand since the 1970s. It was to be presented not as a cut-down powder to be insufflated (snorted) but as a crystal to be smoked: in other words, as P.

This means of administration was well known in other countries but new to the local dance party crowds (again, including many professionals) where its use began. Meth was initially received as a classier, and more benign, version of speed, but its impact on the most vulnerable users was ruinous. By the mid-2000s, middle-class drug users were beginning to shun P as both dangerous and distasteful, but its use had spread to the young, working class and brown.

As if the genuine problems associated with the meth epidemic weren’t enough, the news media inevitably invented a few more. In 2006, TVNZ’s 20/20 programme staked out small-time pot dealers in Auckland’s Grey Lynn Park and speculated, baselessly, that marijuana was being laced with P.

The fact that methamphetamine could be synthesised with extraordinary yields from pseudoephedrine, then a common constituent of pharmacy cold medications, meant it was profitable and plentiful. And, of course, it fit neatly into the national tradition of home drug manufacture.

The cycles of public panic were familiar, but they were becoming tighter and more urgent. There was another flurry around GHB, a drug with significant potential for accidental overdose, which had entered dance party circles as Fantasy or “liquid ecstasy” in the late 90s. In 2001, 22-year-old Shawn Brenner died of an overdose of the GHB precursor GBL, which was being sold in branded packets as One4B. In 2002, Wellington Hospital emergency staff reported handling 20 acute overdose cases of GHB in the past year. Both GHB and GBL were subsequently added to Schedule B of the Misuse of Drugs Act.

Inventing new stimulants

While all this was going on, Aucklander Matt Bowden was at work on changing everything. In 1997, Bowden, then selling advertising for Performance Car magazine, was approached by a client with a business proposition based around a legal stimulant – a substitute for street methamphetamine. An early attempt to market a product via outlets such as the Hemp Store foundered inside six months when it was found to contain ephedrine, a controlled drug.

Bowden decamped to Australia, where he tried again. Working with a neuropharmacologist, he discovered that a substance called BZP had been shown to have amphetamine-like effects in trials in the 1970s. After a failed approach to the Australian Government to endorse BZP as a legal amphetamine replacement, he returned to New Zealand in 2000 and began marketing Nemesis, the first BZP-based party pill.

Bowden has always insisted his principal goal was to provide a less harmful alternative to methamphetamine, to which he had once himself been addicted. And there may well be some truth in the idea that party pills provided a way off P for some users who were unwilling to give up the late-night lifestyle that had become a feature of young life in the cities. But it went much, much further than that.

Pills containing BZP (often in combination with another piperazine or TFMPP) were initially only available via outlets like The Hemp Store, but they gradually entered the mainstream, entirely unregulated. Bowden seemed to have achieved the regulatory solution he sought when a 2005 amendment to the Misuse of Drugs Act created the restricted substances category, or Class D.

This gave authorities the power to set restrictions on age and place of sale – restrictions that were not put in place, thanks largely to a clash with the provisions of the Hazardous Substances and New Organisms Act. It would not be the last time an official inability to execute on new approaches would have consequences.

Although they were increasingly shunned by experienced drug users who disliked the vile hangover they could produce, the use of “party pills” rapidly became mainstream, as suppliers flooded the market with unregulated products. New Zealanders’ long-held tendency to binge came into play – both with respect to the pills themselves and in conjunction with alcohol.

Although there were no party pill deaths, their use kept hospital emergency departments busy enough that it was no surprise when the Expert Advisory Committee on Drugs recommended a ban on BZP and TFMPP, which was enacted the following year.

By this time, the next problem was already brewing: synthetic cannabinoids. These marijuana substitutes (some of them manufactured by Bowden) were set to be the first real test of the Pyschoactive Substances Act, a world-leading attempt to regulate new psychoactive substances rather than simply banning them. The Act’s failure of that first test is too recent to traverse in a history like this, but it centred on flawed official execution, a dramatic media panic and, probably, the unsuitability of most synthetic cannabinoids for regulated sale.

Time for a reboot

While the screws continue to tighten on one of the original coloniser drugs – tobacco – and some moves have been made to haul back the 1980s liberalisation of alcohol, which remains our most harmful psychoactive drug, we’re still a hot mess around the others.

Last year’s report Recent Trends in Illegal Drug Use in New Zealand, 2006– 2011 found all the major illicit drugs still in use and noted the emergence of new drugs such as “synthetic LSD” (relatively risky drugs in the NBOMe class) and trends in the abuse of prescribed drugs, especially oxycodone and Ritalin. Pills allegedly containing ecstasy (but often something else, thanks to a global crackdown on MDMA precursors) remain a staple of summer festivals and dance parties, and marijuana is no less common.

A reboot of the Misuse of Drugs Act 1975 is due next year, on the heels of a ministerial dismissal of the Law Commission’s review of the Act (which is described as “inconsistent with the official drug policy adopted in New Zealand”) and amid substantial confusion as to the way forward. The Act remains arbitrarily separated from the Psychoactive Substances Act, which will at some point be tested again when the first new products are submitted for approval.

So that’s where we are in 2014. As we have done for 200 years, New Zealanders still like to get high. And we still don’t really know what to do about that.

Russell Brown is an Auckland-based writer and blogs at publicaddress.net

Recent news

Reflections from the 2024 UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs

Executive Director Sarah Helm reflects on this year's global drug conference

What can we learn from Australia’s free naloxone scheme?

As harm reduction advocates in Aotearoa push for better naloxone access, we look for lessons across the ditch.

A new approach to reporting on drug data

We've launched a new tool to help you find the latest drug data and changed how we report throughout the year.