What’s going on in the smoke filled rooms?

Around the world, tobacco giants are making it known that plain packaging legislation will meet with forceful litigation in international courts and forums. What advice exists for advocates in a field where public health is often perceived as the poor cousin compared to trade? David Slack reports.

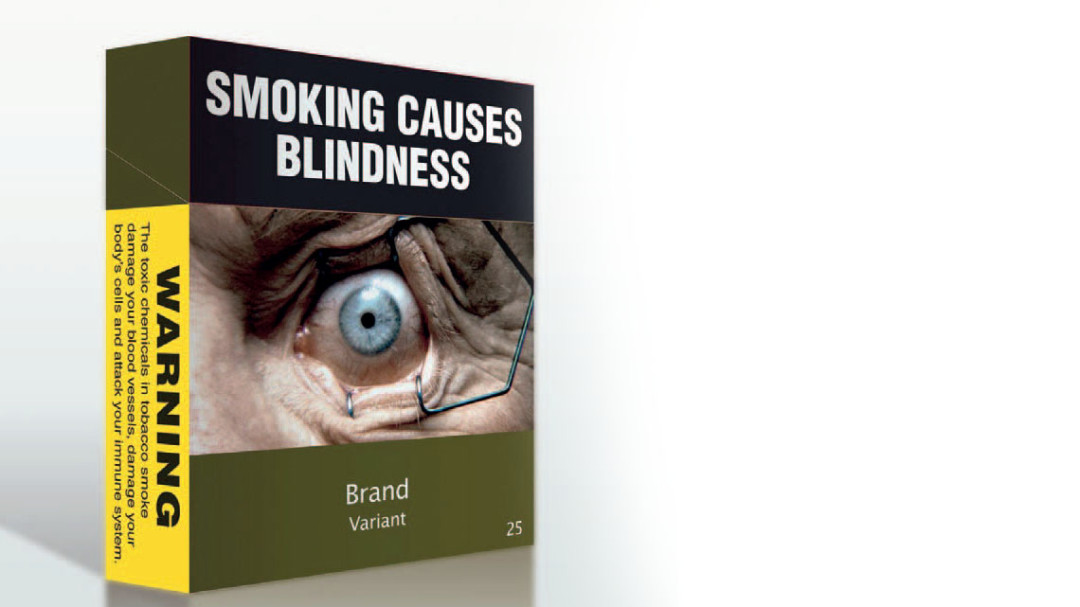

In Australia today, you can buy a packet of cigarettes in any colour you want, so long as that colour is a drab brown. And you can buy that packet with any kind of decoration you like, so long as that decoration is a graphic warning about the dire consequences of smoking.

The world’s tobacco giants have found this an unedifying prospect. Mark our words, they said, we’ll be seeing you in court. True enough, British American Tobacco, Imperial Tobacco Australia Limited, Philip Morris and Japan Tobacco International brought a suit asserting that Australia was helping itself to their intellectual property rights and goodwill. Not so, said the High Court in 2012. It is not a policy that sets out to acquire anything; it is a policy to discourage people from smoking. The policy proceeded.

But it takes more than one bad day in court to deter a multinational corporation. If there’s a courtroom that’ll hear them, they’ll be there. If there’s a trade agreement being negotiated somewhere in the world, they’ll gladly pay a visit. If those negotiation rounds are being held behind closed doors, they’ll be content to kill a few days by the pool. If there’s a forum hearing trade disputes between sovereign states, they’ll be more than happy to help out a nation that sees things their way.

And so Australia, that brave yellow and green canary, stands resolutely in the mine as the legal challenges accumulate.

“The government has breached an international treaty,” said Philip Morris spokesperson Chris Argent. “Plain packaging will damage the value of our brands, and there are international business laws against that.”

Were it not for the fact that the marketing of tobacco brings death on such a monumental scale, the whole business could almost pass for comedy.

It cannot be easy to assert with a straight face that Australia’s plain packaging laws “erode the protection of intellectual property rights” and “impose severe restrictions on the use of validly registered trademarks”. But this is what people are declaring, for money, in the name of the proud nation of Ukraine before the World Trade Organization (WTO).

It is truly a small world when Philip Morris Switzerland finds the need to challenge Uruguay’s tobacco packaging measures under a bilateral investment treaty and Philip Morris Asia acquires an interest in Philip Morris Australia a few months after Australia’s plain packaging measures are announced and then challenges them under a bilateral investment treaty between Australia and Hong Kong.

And now into the mix comes the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) – a bold initiative to open borders to foster trade across the Pacific and perhaps also trample all over the sovereign rights of nations, depending on who you talk to and depending on which leaked section of the agreement you have in your hands.

Is all this litigation a doomed last stand by the tobacco companies, or have they astutely bought themselves the means to continue selling a product that kills five million people a year? Could the TPP give them a renewed licence?

Fifa Rahman, a policy manager at the Malaysian AIDS Council, whose work spans tobacco policy, access to medicines, trade and health, notes the discouraging history of trade disputes. While France did indeed prevail in the European Court of Justice defending its law controlling the advertising of alcohol and tobacco, that stands as something of an exception. In trade disputes, the public health exception has failed, she says, 34 out of 35 times.

That’s not to say sovereign nations have no power, she adds. “I don’t think it’s fair or safe to assume local laws have no power ...local laws are very enforceable.” Rather, the issue for developing nations is the affordability of responding to trade actions.

“Legal fees can go into tens or even hundreds of millions.” These trade disputes – or just the mention of them – are acts of intimidation, she says, by corporations whose business – declining in the first world in the wake of public health initiatives – grows apace in developing countries.

No surprise, perhaps then, that Malaysia proposed a ‘carve-out’ initiative by which tobacco control measures would not constitute any breach of obligations created in the TPP agreement. Fifa Rahman credits this initiative to people power. “We had protestors saying to the government: ‘You don’t care about the Malaysian people’.”

Other nations, New Zealand included, have indicated their support for the concept. But is a carve-out advisable? Is it possible that a conflict between trade and public health laws, in which trade would hold the trump card, is being overstated?

In the forthcoming book Regulating tobacco, alcohol and unhealthy foods: the legal issues, Jonathan Liberman, Director of Australia’s McCabe Centre for Law and Cancer, considers the larger framework in which public health and trade laws operate.

There seems to be a functional harmony between the WTO and World Health Organization.

He notes that the 2012 Ad Hoc Interagency Task Force on Tobacco Control stated, “It should be clarified at global trade forums that World Trade Organization agreements and implementation of the Convention are not incompatible so long as the Convention is implemented in a non-discriminatory fashion and for reasons of public health.’”

Uncertainty grows, he writes, when you move into the area of international investment agreements. Dispute resolution under those agreements can be less transparent, and they are not part of a unified system. Generally, they are not subject to appeal. That can make it look like dangerous territory, but, he argues, “these uncertainties can be, and are, exaggerated and exploited by those who have an interest in persuading governments that they are unable to act”.

He takes issue with advocates putting worst-case scenarios about the ways agreements might be interpreted and applied. “Such advocates at times say things that are strikingly similar to things the tobacco industry routinely says to governments in its efforts to dissuade them from implementing tobacco control measures.”

Although he acknowledges the value of public health advocates concerning themselves with trade and investment agreements, he notes that advocates have “a responsibility to engage in a nuanced and sophisticated way, understanding that the things they say in one forum – where their intention is to portray the constraints of trade and investment agreements as crippling – may prove highly damaging in others”.

How best, then, might a public health advocate deal with threats, perceived and real, to their work? How should they regard an agreement such as the TPP?

Liberman advocates the value of sound legal thinking to reinforce the work public health is doing in an increasingly complex and connected world.

Because health and risk factors for non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are the product of social and economic conditions improving them is a social and economic policy issue.

He would like to see NCD governance capturing some of the risk factors within a single sensible and manageable framework, “allowing for necessary streamlining in governance and the learning of lessons across the risk factors, while concurrently allowing each to be treated on its health, political and legal merits”.

His is an argument for sustained communication and consultation between the concerned parties. An intricate understanding of likely or possible legal challenges, and the substantive issues on which their resolution is likely to turn, can inform, for example, the drafting of legislation in a way that makes it more likely to withstand them.

What is required is sufficient engagement and sufficient recognition of the respective roles all parties play in a complex world. Players on the same public health team could benefit from a better game plan. “Lawyers and public health researchers should not be learning to understand each other’s languages and disciplines for the first time under the pressures of defending large-scale litigation.”

In a similar vein he offers the example of panels and tribunals who adjudicate on trade matters, who may well take the view that a given public health policy has a valid role but may not be sufficiently conversant with that policy to judge its place relative to a trade agreement. “It is unrealistic to expect trade and investment panellists and tribunal members to become overnight public health experts,” he acknowledges, “but it is perfectly reasonable to expect them both to appreciate the limitations of their own expertise, and to show an appropriate degree of deference to public health imperatives, values and approaches and to governments’ regulatory choices.”

Notwithstanding the uncertainties and the guesswork that attend these issues, one truth is undeniable. A lack of clarity is serving the interest of one party more than any other: multinational tobacco corporations. As long as they can declare to wavering governments: “Don’t go implementing this legislation until you’ve seen how much of a hammering Australia will get” and as long as debate can impede any comprehensive strategy for tackling NCDs, delay and doubt are their very best and, arguably, only friends. They are keeping them close.

Recent news

Reflections from the 2024 UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs

Executive Director Sarah Helm reflects on this year's global drug conference

What can we learn from Australia’s free naloxone scheme?

As harm reduction advocates in Aotearoa push for better naloxone access, we look for lessons across the ditch.

A new approach to reporting on drug data

We've launched a new tool to help you find the latest drug data and changed how we report throughout the year.