Guest editorial: Towards global drug policy pathways that work

Ahead of the UN General Assembly Special Session (UNGASS) on Drugs in 2016, the Global Commission on Drugs proposes a new drug control regime for the 21st century. The experience of what regulation means in practice is informing policy, as Steve Rolles explains

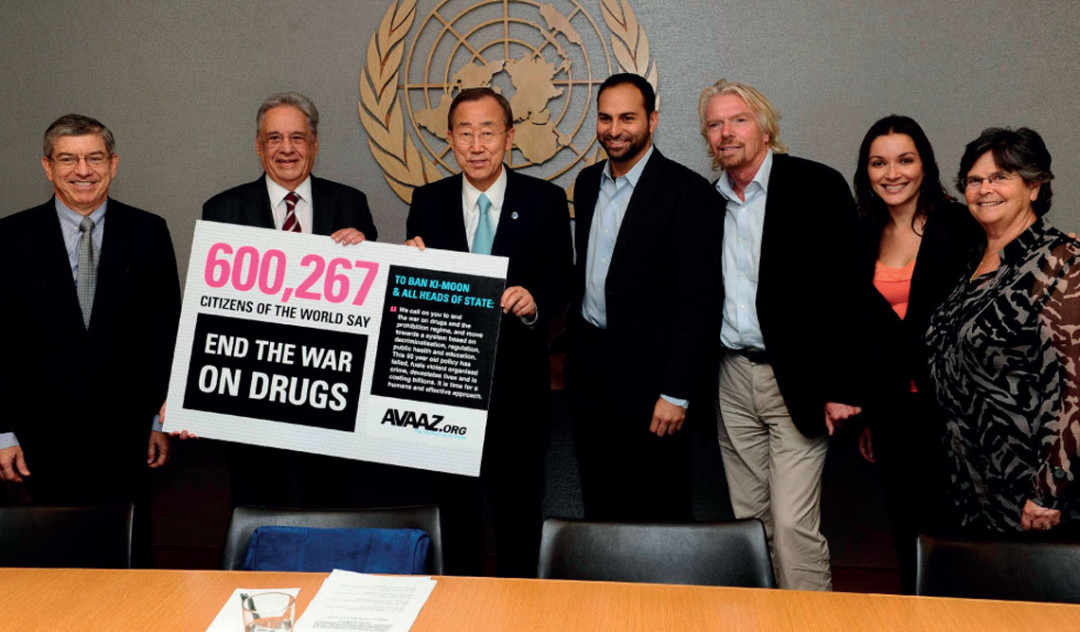

On 9 September, the Global Commission on Drugs released its latest report Taking Control: Pathways to drug policies that work in New York. The Commission is made up of political leaders including seven former presidents, UN luminaries, including former Secretary- General Kofi Annan, and high-profile public figures, including businessman Richard Branson and Paul Volker, former head of US Federal Reserve.

The Commission had a huge impact in 2011 with its first report, War on Drugs. This report represented the most highly powered group thus far to argue for a substantive re-orientation of drug policy from the failings of a punitive enforcement led paradigm to a health and human rights based approach. Most prominent were the calls for decriminalisation of drug users and experimentation with legalisation and regulation of some drugs. The second and third reports focused on the impacts of the war on drugs on the epidemics of HIV and hepatitis C.

The new report returns to and develops the themes of the first, but notably with a new emphasis on the questions of regulation and UN-level reforms (see box). The accelerating pace of drug policy reform since 2011 is acknowledged. This is occurring in spheres of both decriminalisation and harm reduction and with the first cannabis regulation models being implemented in the US and Uruguay. As the regulation debate moves from theory to reality, a substantial section of the report focuses on providing more detail about what regulation means in practice – attempting to address many of the popular concerns and misconceptions.

New Zealand’s groundbreaking 2013 legislation to regulate certain novel psychoactive substances is presented as part of this global drug policy reform process. For anyone in New Zealand doubtful of the law’s significance, the 2013 Act is used as one of the examples of innovative new thinking on regulation models around the world. The approach has clearly informed the recommendations which specifically encourage “diverse experiments in legally regulating markets in currently illicit drugs, beginning with but not limited to cannabis, coca leaf and certain novel psychoactive substances”.

Whilst the Commission’s recommendations are familiar territory for reform NGOs, the greatest political significance of the report perhaps lies in the Commissioners themselves. The 2011 report helped create political space for increasingly high-profile public figures, including – for the first time – sitting heads of state, to openly question the War on Drugs and call for meaningful exploration of alternative approaches. It helped ‘break the taboo’ on high-level drug policy reform debate as it set out to do.

The most significant manifestation of this new openness was the call in September 2012 from the presidents of Colombia, Mexico and Guatemala at the UN for a Special Session of the General Assembly (UNGASS) to review and reform the global drug control framework. The 2016 UNGASS that resulted is another key focus of the new report. Recommendations are clearly designed to inform the UNGASS deliberations, with a key final section on what UN-level reform entails. It suggests not only that the punitive paradigm underlying the UN drug treaties needs to be reconsidered, but ultimately that the drug treaty system itself needs to be revisited and modernised to make it ‘fit for purpose’.

The Global Commission report’s key recommendations

Put people’s health and safety first

Instead of punitive and harmful prohibition, policies should prioritise the safeguarding of people’s health and safety. This means investing in community protection, prevention, harm reduction, and treatment as cornerstones of drug policy.

Ensure access to essential medicines for pain control

The international drug control system is failing to ensure equitable access to essential medicines such as morphine and methadone, leading to unnecessary pain and suffering. The political obstacles that are preventing member states from ensuring an adequate provision of such medicines must be removed.

End the criminalisation and incarceration of people who use drugs

Criminalising people for the possession and use of drugs is wasteful and counterproductive. It increases health harms and stigmatises vulnerable populations and contributes to an exploding prison population. Ending criminalisation is a prerequisite of any genuinely health-centred drug policy.

Refocus enforcement responses to drug trafficking and organised crime

A more targeted enforcement approach is needed to reduce the harms of the illicit drug markets and ensure peace and security. Governments should deprioritise the pursuit of non-violent and minor participants in the market, instead directing enforcement resources towards the most disruptive and violent elements of the drug trade.

Regulate drug markets to put governments in control

The regulation of drugs should be pursued because they are risky, not because they are safe. Different models of regulation can be applied for different drugs according to the risks they pose. In this way, regulation can reduce social and health harms and disempower organised crime.

Global leadership for more effective and human policies

The evolution of an effective, modern international drug control system requires leadership from the UN and national governments, building a new consensus founded on core principles that allows and encourages exploration of alternative approaches to prohibition.

Recent news

Reflections from the 2024 UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs

Executive Director Sarah Helm reflects on this year's global drug conference

What can we learn from Australia’s free naloxone scheme?

As harm reduction advocates in Aotearoa push for better naloxone access, we look for lessons across the ditch.

A new approach to reporting on drug data

We've launched a new tool to help you find the latest drug data and changed how we report throughout the year.