The cruel 'C'

The outlook for those suffering from hepatitis C is pretty bleak. It’s an unwelcome disease with unwelcome symptoms, both physically and psychologically, and sometimes the cure is the most unwelcome of all. At least here in Godzone. Russell Brown looks at the New Zealand situation and some encouraging treatment developments overseas.

1992 was a bad year.

That was the year hepatitis C notifications in New Zealand jumped nearly fourfold over the previous year to 89 cases.

There were a number of reasons for the spike, including that awareness of the new liver disease had recently spread amongst doctors - the hepatitis C virus was only formally identified in 1989, and it was still being notified as ‘non-A, non-B’ in this country - but it was the first real sign of what would come to be called the ‘silent epidemic’.

This year, between 700 and 1,000 new cases of hepatitis C will be notified, adding to a population of at least 50,000 New Zealanders, many of whom have no symptoms and do not even know they have the disease. The numbers could be higher. Unlike Australia, our system only notifies acute infections and not patients with chronic disease who may have been infected for 20 years but have only recently sought help.

Behind the numbers are the human stories – people who have lived impaired lives of constant fatigue and disability or who have succumbed to hepatitis C’s twin end-game: liver cirrhosis and failure or liver cancer. Some live with the knowledge that they have infected loved ones or their own new babies.

And then there is the stigma. Although medical ‘bad blood’ infection is among the leading causes of death in people with haemophilia, and there has been an increase in recent years of sexual transmission between men who have sex with men, the overwhelming cause of infection is injecting drug use. Even if it happened 30 or 40 years ago, it’s not something you want your workmates to know. At times, past drug use has even been cited to deny treatment.

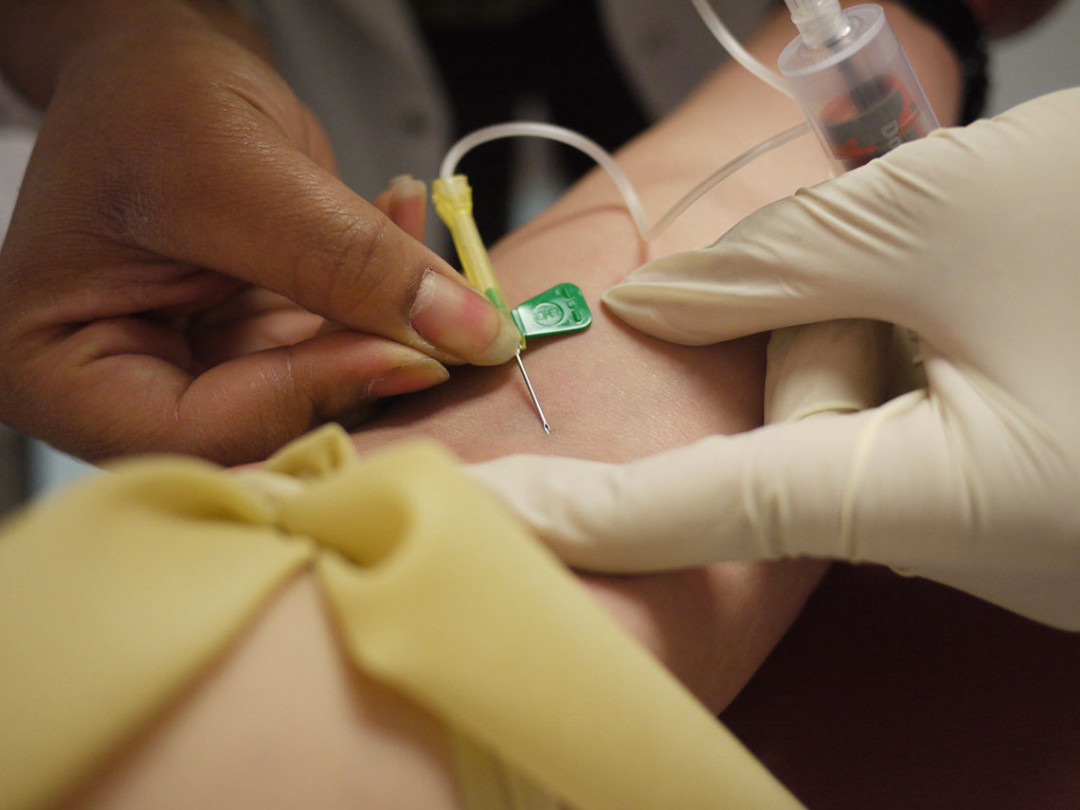

Cruelly, the ‘cure’ is, for many, worse than the chronic disease. The established treatment for hepatitis C, interferon, involves weekly injections supplemented with six daily tablets of ribavirin for 48 weeks. Interferon bolsters the body’s immune system in the hope that it can overcome the virus, but it also depletes the brain’s stock of serotonin, inducing symptoms of clinical depression in most patients.

“Let no-one say otherwise,” author and historian Redmer Yska has written of his own experience with interferon, “it is inhumane treatment.”

And even though results have improved considerably over the past 25 years, nearly half of those who undergo the ordeal of interferon will find, as Yska did, that it has not cleared their virus.

What if there was a way to make all that go away – to even eliminate hepatitis C itself? There is, but in New Zealand, the bargain has yet to be struck.

In 1992, Dr Ed Gane travelled from Auckland to Britain to find out about hepatitis C. At the time, little was known about its long-term effects, and some specialists had even declared that it was not harmful. Gane found otherwise.

“In 1992, I tested 500 samples from people who’d been transplanted and found out that, yes, indeed, the most common cause for liver failure was hepatitis C, and that was really the first time that had been demonstrated,” he says. “So I was very lucky to be in the right place at the right time.”

Gane, now Deputy Director and Hepatologist at the New Zealand Liver Transplant Unit at Auckland City Hospital and Clinical Professor of Medicine at the University of Auckland School of Medicine, is still, as he modestly puts it, “in the right place at the tight time”.

Over the past four years, principally through a partnership with the US drug company Gilead, Gane has overseen trials of a new generation of direct anti-viral drugs that have shown a 98 percent cure rate for hepatitis C. Treatment – one tablet a day for 12 weeks – has no side effects.

Nearly 1,000 people have been cleared of the virus by participating in the trials in Auckland, Christchurch, Hamilton, Tauranga, Wellington and Dunedin, and a smaller group of very sick patients with liver failure has been treated in Auckland and Christchurch under a compassionate programme agreed with Gilead. Those patients can be cleared of the virus before receiving a transplant – meaning the new liver won’t be infected. In some cases, the eradication of the virus may enable the patient’s liver to recover to such a stage that they no longer need the liver transplant.

…at least 50,000 New Zealanders, many of whom have no symptoms and do not even know they have the disease.

Patients I spoke to for this story talked with emotion about regaining their lives. Those who had been under Gane’s care all praised him personally.

Although Gilead’s product, Harvoni, has been approved for use in New Zealand by Medsafe, it is not yet funded by Pharmac, and a 12-week course of treatment will cost around $80,000 or more.

Allison Beck, a peer health worker and educator with the Hepatitis C Resource Centre Otago Southland, says many of her clients are aware of the new drugs and ask about them.

“But generally, my clients don’t have $100,000.”

Beck’s client base is an ageing one, mostly male, aged 50–60, “heading towards liver disease”. Many have vulnerabilities and are unwilling to embark on interferon treatment.

“For them to put themselves at risk psychologically is something they’re quite scared about.”

Gane says many of those with the virus are now holding off interferon in the hope that Pharmac will fund one or more of the new anti-virals. The numbers are “steadily decreasing”, and only 300–400 will be treated this year through Pharmac-funded therapy.

A deadline is looming. Pharmac is negotiating with Gilead and others on price, but with three new drugs trialled already in New Zealand and another two likely next year, trials could be over within two years.

The new anti-virals are available through the public health systems in France and Germany and via health maintenance organisations in the US (who have complained publicly about the $1,000 a tablet price tag, in some cases threatening to ‘warehouse’ patients in anticipation of cheaper drugs). They’re also available in India and Egypt, which both have epidemic infection rates (Egypt’s is around 15 percent of the population), for as little as 1–2 percent of the developed-world price. Both Gane and Beck acknowledge that New Zealand patients are looking at Indian-based online pharmacies but agree it’s hard to know how legitimate the sites are.

“I’m not trying to say don’t do it,” says Gane. “I’m just not sure of how you access it legitimately, how you pay for it and how you can be sure the drug is not a fake.”

The number of new anti-virals is in itself a hopeful sign. Gane notes that, when a second drug from AbbVie was approved in the US last year, the price of the first fell immediately. With Merck’s recent entry to the field, specialist publications are calling it a “race”.

There is little doubt that funding even an expensive anti-viral would represent a long-term saving for the taxpayer. Caring for a liver cancer patient is very costly – a liver transplant even more so.

Gane notes a study in Melbourne in which doctors are treating current injecting drug users, “and they’ve been able to turn off all new infections in Victoria. What that shows is that we don’t just treat the sickest people on the waiting list, we have to treat everyone. And if you do that, including those people who are sill injecting, it’s what we call treatment as prevention – and we will actually eliminate hepatitis C without a vaccine within the next 15–20 years.

“In our clinic, instead of treating, say, 10 people a year, we could easily treat 100 people a year with no increase in numbers of people we need in the clinic. It’s so easy. I truly believe that, once the prices come down, treatment won’t be in the hospital any more, it’ll be in the community.”

Let no-one say otherwise,” author and historian Redmer Yska has written of his own experience with interferon, “it is inhumane treatment.

The benefits will be even greater outside Auckland. Beck notes that her region has no liver transplant unit, and Invercargill has only one specialist nurse able to administer interferon.

There’s also a social problem: the stigma. “There’s a lot of stigma, a lot of discrimination against people with hepatitis C, purely because they’ve acquired it through practices like injecting drug use. What we would love to have is more people, more patients being advocates for people with hepatitis C. We’re trying to work on that.”

Beck agrees her status as a former hepatitis C patient (she was cleared with interferon) helps clients pluck up the courage to go to medical professionals. The bottom line, says Gane, is that the disease is completely curable. “Every death from hepatitis C is a preventable death. We have the means to not only cure individual patients but also to eliminate [the hepatitis C virus] from New Zealand. We just have to somehow get the government to pay for it.”

The cruel 'C': very human stories

‘Jean’ – senior civil servant, infected through IV drug use, cured in an Auckland drug trial with sofosbuvir, ribavirin and ledipasvir.

“One of the most memorable things was when they told me about my viral load – it had gone from over 3 million per millilitre of blood to undetectable in a period of two weeks … I think the psychological impact has been the most profound – it was like having the sword of Damocles lifted. For years, every time I had an ache or pain, I would worry that something was wrong – liver cancer had got me. I didn’t count on a future old age or feel confident making those sorts of plans. It was quite subtle really, but once it was gone, I was able to see how much it had impacted on me.”

Redmer Yska – author, infected through IV drug use in the 1970s, virus returned after interferon treatment, cured last year via a three-month trial with Sovaldi and interferon.

“After 40 years of living with this horrible virus, it is finally out of my system. I feel lighter, my brain feels like it is working better. Most of all, I’m chuffed that, along the way, I played my part in looking after myself. And I did that by not drinking and making things worse.”

‘Jean’ – mental health worker, infected through IV drug use in the 1970s.

“A friend and I have just finished three months on the new Viekira Pak. We are both genotype 1A, the difficult one to treat. I’m clear a month after treatment. I was in the first protease inhibitor trials years ago. We have been waiting years for this after finding the old interferon/ribavirin treatment too brutal to finish the course. I am very grateful to Ed for giving us this treatment – there were only eight compassionate doses available in Auckland. Some side-effects but not nearly as bad as the old interferon regime.”

George Henderson – musician, infected through IV drug use in the 1990s, cured last year via the Auckland -based ‘Vulcan’ trial with sofosbuvir and GS-5816.

“Amazing. Pharma made something that worked, cured a disease that, as far as I’m concerned, had no cure before.”

‘Maisie’ – council officer, infected through IV drug use in the early 1980s, cured in an Auckland drug trial.

“Within two weeks, I knew I was on the drugs not the placebo – the change was very powerful. I had so much energy, I had to check with my nurse that I wasn’t having some kind of manic episode … Things continued to get better, the fog was clearing. My terrible sleep patterns became seven hours of good solid sleep, aches and pains lessened, feelings of anxiety and general malaise disappeared. “Four years on, I feel like one of the luckiest people on the planet. I would likely have died early after years of shit health. I have a pretty damaged liver, but it’s not struggling against a virus and is doing fine. I have a beer or two now and then and sometimes wish that I hadn’t made such bad choices back in the day but, hey, who doesn’t?”

‘Reg’ – probably infected during surgery in Christchurch in the 1980s, cured with interferon and an early anti-viral in 2007.

“I think the worst thing about hep C was the reaction of the mainstream and some friends. I was so surprised at how many of my friends owned up to having it, but talking about it had its risks. I had life insurance back then – the premium tripled and cut off at 50, so I abandoned that. Telling dentists or doctors got an instant negative reaction and made you feel like a leper – often left alone while hushed, scared voices worked out how they would approach it. I just stopped telling as I realised I was limiting my options.”

‘Barry’ – infected 20 years ago through IV drug use.

“I was diagnosed by chance three or four years ago and didn’t think much about it. I declined interferon because of what I’d heard about it. Then last year, I pretty much threw up and shit out all my blood for about a week. I figured I was dying. I had up to four blood transfusions a week, and when I was somewhat stabilised this year, they got me on a compassionate six-month course of Sovaldi. Still a couple of months to go.”

What are the drugs?

Trialled at various sites in New Zealand so far:

Gilead Sciences’ Harvoni – a combination tablet of sofosbuvir (a polymerase inhibitor sold separately as Sovaldi) plus ledipasvir (NS5A inhibitor). Already approved in New Zealand but not funded. AbbVie’s

Viekira Pak – a combination of paratevir (protease inhibitor) and ombatisvir (NS5A inhibitor) and dasabuvir (polymerase inhibitor). Expected to be approved in New Zealand later this year but not funded.

Merck’s combination MK2 – a combination of grazoprevir (protease inhibitor) and elbasvir (NS5A inhibitor). Expected to be approved in New Zealand next year but not funded.

Russell Brown blogs at publicaddress.net

Recent news

Reflections from the 2024 UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs

Executive Director Sarah Helm reflects on this year's global drug conference

What can we learn from Australia’s free naloxone scheme?

As harm reduction advocates in Aotearoa push for better naloxone access, we look for lessons across the ditch.

A new approach to reporting on drug data

We've launched a new tool to help you find the latest drug data and changed how we report throughout the year.