Opinion: A brave, new drug policy

The National Drug Policy 2015-2020 is finally out. How does it stack up? Drug Foundation Principal Policy Advisor Andrew Zielinski looks at the pros and cons and whether the policy will take us where we need to go.

The curiously long wait for a new national drug policy had some of us concerned about the government not prioritising drug harm reduction. But the National Drug Policy 2015–2020 is now out and despite the delay, there are aspects to applaud. Minister Peter Dunne’s concepts of compassion, proportionality and innovation herald a promising new direction.

The old policy’s harm-minimisation goal, based on the familiar strategies of supply control, demand reduction and problem limitation, remains a sound approach. However, a range of useful objectives and priority areas have been added to the policy’s framework. These give it more logic and flow and make it more self-contained. It’s unfortunate, though, that the ‘Reducing alcohol and other drug-related illness and injury’ objective doesn’t extend to reducing social harms. Interestingly, tobacco has completely dropped out of the policy, focussing it on alcohol and psychoactive drugs.

We’re particularly happy to see focus on a new objective: ‘A shift in attitudes towards alcohol and other drugs’. Reducing social stigma towards people with alcohol and other drug problems is vital to address the issue of the 50,000 people a year who want help to reduce their alcohol and other drug use but don’t get it.

Another important improvement is the addition of indicators to assess progress with objectives. While we would have liked to see more illegal drug-related indicators, like a criminal justice indicator or two, the indicator on opioid poisonings is very welcome.

We also welcome the priority areas added to the policy, particularly ‘Improving information flow’, ‘Getting the legal balance right’ and ‘Shifting thinking and behaviour’. We’ve long been highlighting the need for better information to inform drug policy and it’s frustrating that ‘Evidence online’, as promised in the old policy, has not yet eventuated.

This brings us to our main concern with the policy – a lack of focus on more comprehensive drug law reform.

The addition of specific actions for completion by 2017/18, associated with priority areas, is also positive. We particularly welcome an action supporting schools to keep students in education, but we consider there should have been an action on opioid overdose prevention work including naloxone use, which will save lives.

Finally, it’s especially promising to note the addition of the ‘Getting the legal balance right’ priority and associated action to “develop options for further minimising harm in relation to the offence and penalty regime for personal possession within the Misuse of Drugs Act 1975”. However, this brings us to our main concern with the policy – a lack of focus on more comprehensive drug law reform.

The case for drug law reform

The Misuse of Drugs Act (MoDA) is 40 years old and should be comprehensively redesigned to reflect drug harm reduction best practice. MoDA was developed in the 1970s when New Zealand’s cultural context and drug scene were very different.

Back then, the average New Zealander not part of the ‘hippie’ counterculture had little or no exposure to illegal drugs. Today, nearly half of New Zealanders have tried something illegal. The prevailing international approach was that drug use was a criminal justice matter best controlled through legislated deterrence and punishment. President Nixon started the ‘War on Drugs’ in 1971.

New Zealand’s drug market is also radically different from the 1970s when cannabis, heroin and psychedelics like LSD prevailed. While cannabis continues to be our most popular illicit drug, new ‘designer drugs’ like ecstasy (MDMA) have arrived, and methamphetamine now features on the scene.

The most fundamental change, though, has been the growth of new psychoactive substances not necessarily covered under MoDA. Many different and potentially harmful new substances are available – most recently, synthetic cannabinoids and drugs like ‘synthetic LSD’ in the risky NBOMe class. We had around 200–300 new psychoactive substances on the market prior to the Psychoactive Substances Act 2013. These substances are cheap to make and hard to detect, with little available safety information for consumers. And they will keep coming.

The internet has also dramatically altered the drug market, with ‘dark-net’ sites like Silk Road (replaced by new sites like Agora and Evolution) enabling people to buy drugs anonymously using digital currency.

So, our drug scene has changed markedly. But while MoDA has been amended 18 times in the past eight years, it’s failed to keep pace with changes and now exists as a patchwork of poorly considered amendments and outmoded assumptions.

Internationally, recognising that strict prohibition has failed to reduce illicit drug demand or harms, there have been various innovative reforms. Fifteen countries have decriminalised the personal possession of all drugs. Portugal decriminalised all drug use in 2000 and developed strong new policies on prevention, treatment and harm reduction. This approach is working, with drug use, offenders in prison, court cases, HIV infections and overdoses all decreasing.

In the US, cannabis is decriminalised or legal in some form in 27 states and the District of Columbia. Four US states have legalised recreational cannabis. South Australia decriminalised minor cannabis offences almost 30 years ago in 1987, with the Australian Capital Territory and Northern Territory following suit in the 1990s.

Our Psychoactive Substances Act is potentially a globally innovative way to control newly emerging drugs by regulation, only allowing safe products.

Unfortunately, amendments to that Act have meant continued prohibition, and problems with black market supply are emerging. Meanwhile, MoDA retains a strict prohibition approach for all our established drugs, with harms persisting.

Statistics NZ figures record that in 2014 there were 871 people aged 17 and over prosecuted for illicit drug use/possession as their most serious offence, with 661 of those convicted and 26 of those imprisoned – yet we still have some of the highest drug use rates in the world, with one in 13 adults over 15 years smoking cannabis at least once a month.

So, what type of reform do we need?

Our approach needs to shift from being predominantly criminal justice based towards a health and social focus. We must acknowledge that MoDA’s punitive approach, heavily weighted towards supply control, is ineffective and harmful.

As the UK Home Office recognises:

“The disparity in drug use trends and criminal justice statistics between countries with similar approaches, and the lack of any clear correlation between the ‘toughness’ of an approach and levels of drug use demonstrates the complexity of the issue.”

We must align our law more with harm reduction principles. This means addressing the health and social problems underlying demand for drugs and minimising the problems arising from inevitable drug use.

A wealth of evidence since the 1970s tells us this is what works. A first step would be not criminalising people for personal use/possession offences but using such ‘infringements’ to caution, give information, make health assessments and offer treatment (akin to the Law Commission’s recommended mandatory cautioning scheme).

But if we’re really serious about drug harm reduction, we need to start thinking about smarter control of more of our currently illicit drugs. This means making drugs available under strict regulation in much the same way we’ve been trying to deal with new psychoactive substances.

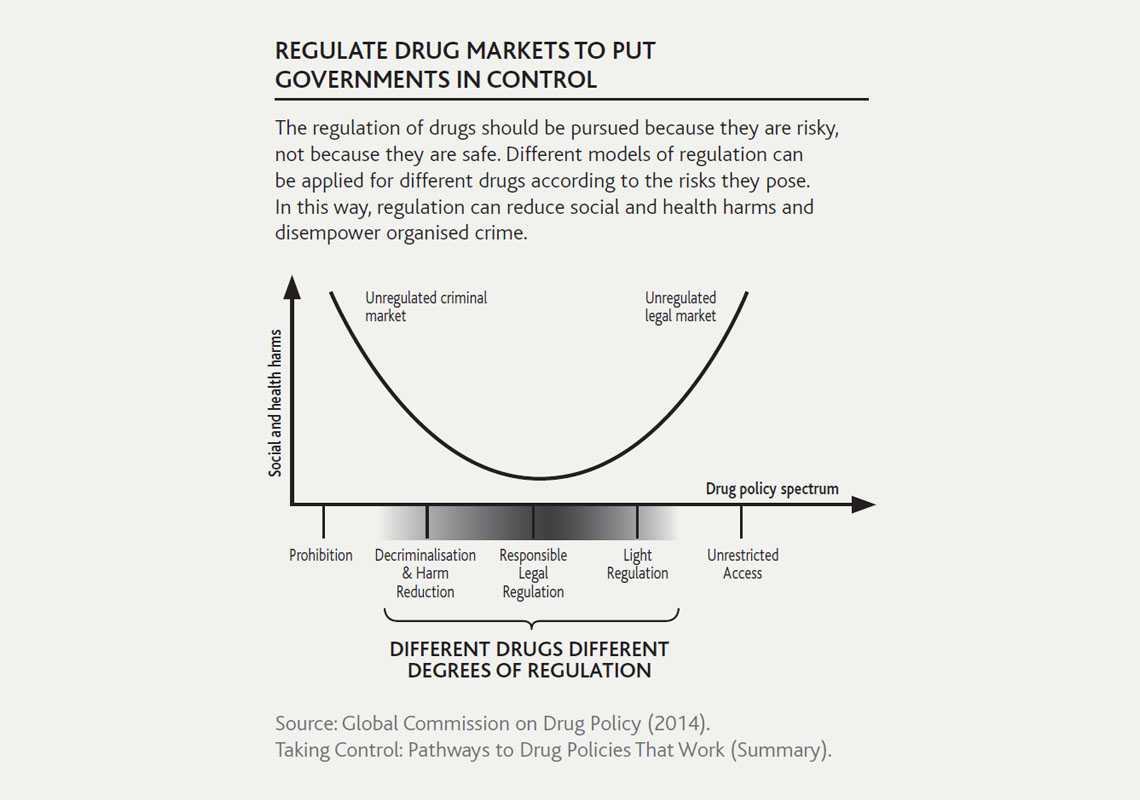

It doesn’t mean liberal availability and promotion as is the case with alcohol. MoDA’s prohibition model works against the harm minimisation principles of our national drug policy by leaving non-pharmaceutical drug production and sale in the unregulated hands of criminal elements. To best enable harm reduction, control of the whole drug market should, carefully, begin to be taken back by government and wider society. This concept is well expressed by the Global Commission on Drug Policy’s diagram below:

Greater social and health harms occur at both ends of drug policy spectrum from Prohibition (Unregulated criminal market) to Unrestricted access (Unregulated legal market). Less harms with Responsible legal regulation. - REGULATE DRUG MARKETS TO PUT GOVERNMENTS IN CONTROL. Social and health harms over drug policy spectrum

Right now New Zealand is, understandably, socially and politically uncomfortable with making currently illicit drugs legally available, even by strict regulation. However, that we enacted the Psychoactive Substances Act shows some level of willingness. Regulating to give control of the drug market back to the government is not radical policy. Actually, it’s the prohibition approach that’s radical, because it removes the levers governments normally use to regulate markets.

Many of the drug harms we currently see are there because profit-motivated criminal drug suppliers are not concerned with public health harm minimisation principles or bound by product safety regulations. If we’re looking boldly towards future drug harm reduction, we need to consider smarter drug regulation.

Photo credit: flickr.com/photos/cjsmithphotography

Recent news

Reflections from the 2024 UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs

Executive Director Sarah Helm reflects on this year's global drug conference

What can we learn from Australia’s free naloxone scheme?

As harm reduction advocates in Aotearoa push for better naloxone access, we look for lessons across the ditch.

A new approach to reporting on drug data

We've launched a new tool to help you find the latest drug data and changed how we report throughout the year.