Moving to a healthy drug law by 2020

Get a copy and give feedback

New Zealand prides itself on being a trailblazer in progressive reform: think marriage equality, the anti-nuclear act, the welfare state and women’s suffrage.

In 2017, we again have the chance to lead the way by burying the failed War on Drugs and putting health at the core of our drug laws and policies.

Both in the political and the public spheres, we have many areas of consensus to build on. For example, we all agree that drugs can – and do – cause harm to some individuals and to wider society. A key goal of law change, therefore, should be to reduce the risk of harm.

There is also sweeping agreement that our current drug control efforts are themselves causing harm. In a democratic country, punishment should be proportionate to the injury caused by the crime.

This is not the case at present. What we have is a regime that burdens young people with drug convictions that stay with them for years and sometimes for their lives. This makes it difficult – if not impossible – for them to obtain jobs and participate fully in society.

On top of that, drugs cost us a lot. The New Zealand Drug Harm Index estimated the total social cost of illicit drug-related harms at $1.8 billion in the 2014/15 year. In that year, the Ministry of Health spent $78.3 million on interventions, while the Police, courts and Department of Corrections spent $273.1 million, mostly on enforcement of our laws.

Money is accordingly being used on ineffective attempts at enforcement rather than being spent constructively on a health-focused approach. We would reverse the ratio of spending. The public is ready to support change. A poll commissioned by the NZ Drug Foundation last year found 64 percent of respondents believe possession of a small amount of cannabis for personal use should either be legal (33 percent) or decriminalised (31 percent).

The results confirm a shift in the community’s mood: regardless of party affiliation, there is consistent support for moving away from the current criminal justice approach to drugs.

We also have growing political support for a new approach, including progressive drug policies developed by United Future, the Greens and The Opportunities Party.

We are fortunate that reforming our drug law does not require us to start from scratch. Within the confines of the Misuse of Drugs Act 1975, we are already under way with positive change.

Excellent drug harm-reduction policies we currently have in place include our needle exchange programmes, opioid substitution treatment, Police warnings and diversion for minor offences and the Alcohol and Other Drug Treatment Court, Te Whare Whakapiki Wairua, in Auckland.

There are also iwi and community justice panels operating in some parts of the country. These provide a constructive means of dealing with minor offending. On top of that, a lot of the thinking needed to underpin a new, health-based approach to drug regulation has already been done. The Law Commission spent four years researching and consulting the public about drug laws between 2007 and 2011.

More than 3,800 submissions were made on its review, meaning that a very broad cross-section of New Zealand was canvassed before the Commission released its final 350-page report.

The Commission made 144 detailed proposals for reform, including calling for repeal of the Misuse of Drugs Act and its replacement with a new law administered by the Ministry of Health.

The report recommended adopting a more effective approach to personal drug use by directing people away from the criminal justice system and into education, assessment and treatment.

New Zealand’s National Drug Policy 2015–2020 dovetails with that approach. It aims to prevent and reduce the health, social and economic harms linked to drug use and to promote and protect health and wellbeing.

The policy regards drug use as a health and social issue and emphasises health-based approaches. This makes it a good springboard from which to launch change.

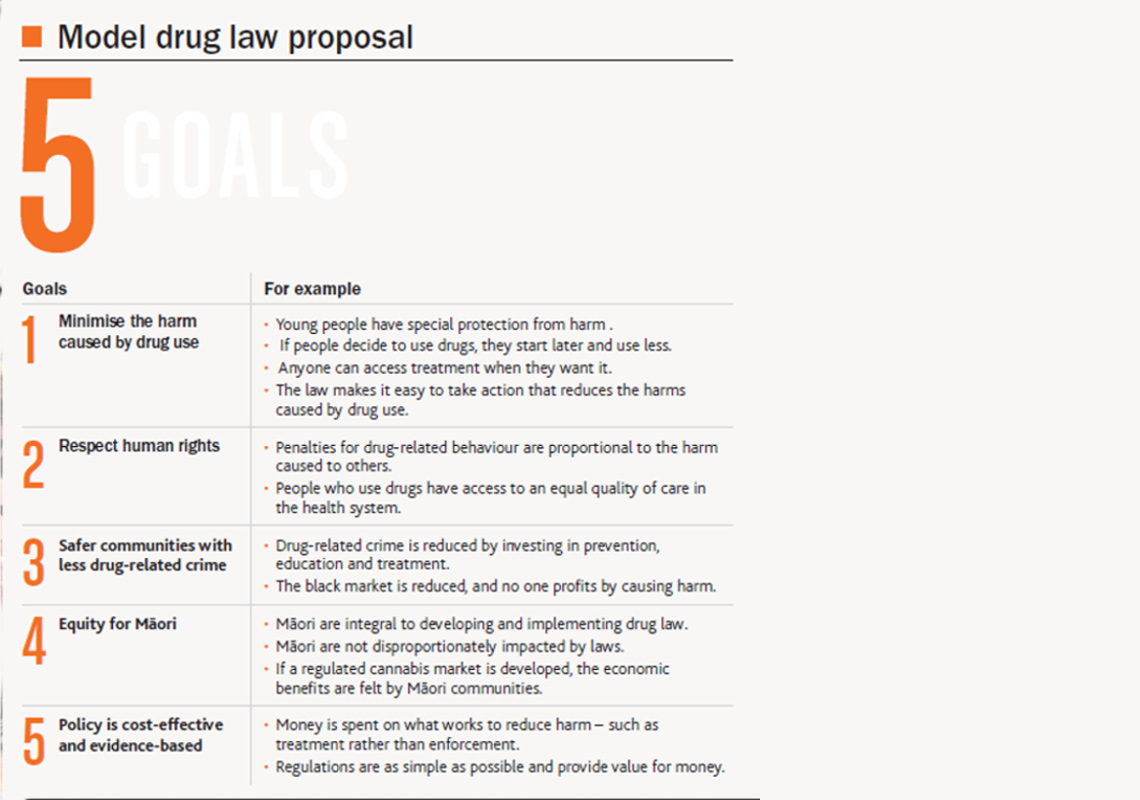

Our five goals - Five goals we should all be aiming for.

Model drug law

In 2017, the time is ripe for us to set a new course and make real our vision of an Aotearoa free from drug harm. So we’ve come up with a model drug law that is about just that. It is built on evidence, research and experience. But it is not our final say – it is a conversation starter. We want to hear from you about how we can improve it.

The model drug law we propose has five key goals (see right), including safer communities as a result of less drug-related crime and minimising the harm individuals, whänau and the community experience from drug use.

These aims have been developed from community workshops we have held around New Zealand over the past year, and they also mesh well with international research on drug reform.

Decriminalise use

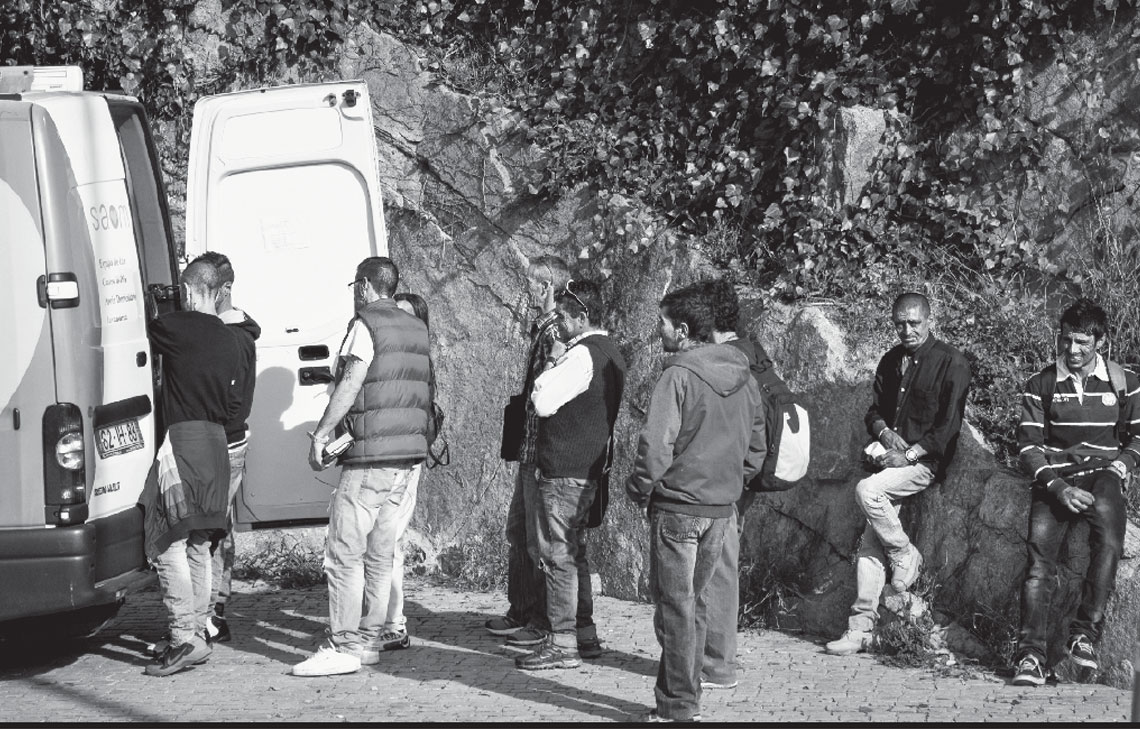

The first part of our model drug law is based on the Law Commission’s 2011 recommendations and the Portuguese model of reform. Portugal decriminalised the use of all previously illicit drugs in 2001 and invested heavily in prevention, treatment and harm reduction.

Drug use is still prohibited in Portugal, but it does not result in criminal penalties in most cases. Portugal’s experience has been that this approach has decreased drug use among young people, led to fewer people in jail and reduced HIV infections and overdoses.

We support repealing the 42-year-old Misuse of Drugs Act and replacing it with a new law administered by the Ministry of Health. Possession, use and social supply would be decriminalised, and possession of drug utensils would no longer be an offence.

As recommended by the Law Commission, Police coming across someone in possession of drugs would issue a caution notice, provide information about how to get help and confiscate the drugs.

After a set number of cautions –depending on the legal classification of the drug – a person would be required to attend a brief intervention session or be prosecuted. Brief interventions would involve a preliminary screening and a discussion about the risks of drug use and whether the person would benefit from social support or treatment.

People who failed to attend the brief intervention session would be prosecuted. As the aim is to keep the focus on improving health outcomes, the small number of people convicted would face low fines or the option of attending treatment programmes.

The model drug law would also require us to review and reclassify current scheduled drugs according to the harm they pose, as there are many inconsistencies in the current classifications.

We also think the current penalties for dealing and manufacturing drugs need review. For example, the current maximum penalty of life imprisonment for dealing in Class A drugs puts such activity on a par with murder, which we consider to be disproportionate.

See our Model Drug Law page for more details.

Mobile health workers in Portugal - Portugal has invested heavily in drug treatment and prevention. Photo credit: Neil Moralee, flickr

Regulate cannabis

Our model also has a separate section covering cannabis. Social and cultural norms about cannabis are changing, as demonstrated by the 2016 poll and by the legalisation of cannabis in eight American states as well as some type of decriminalisation or legalisation in 44 countries.

We know that a majority of people use cannabis without serious health harm. However, a small proportion experience negative impacts such as anxiety, depression, memory loss and mood swings.

Those with sustained use face long-term health risks such as respiratory disease (if smoked) and mental illnesses such as schizophrenia, at least for those who may be predisposed.

Cannabis also carries the risk of dependency in around one in 10 users. Heavy use by young people has been linked to poorer outcomes in education and employment as well as a reduction in IQ points, although the research on this is mixed.

We want to create a system that will make it more difficult for those under 18 to access cannabis than it currently is and will make it easier for anyone struggling with their use to access support. Our regime also aims to discourage mixing alcohol, tobacco and cannabis and to provide excellent prevention, education and treatment. We believe this can be achieved by replacing our current prohibition system for cannabis with a regulatory system.

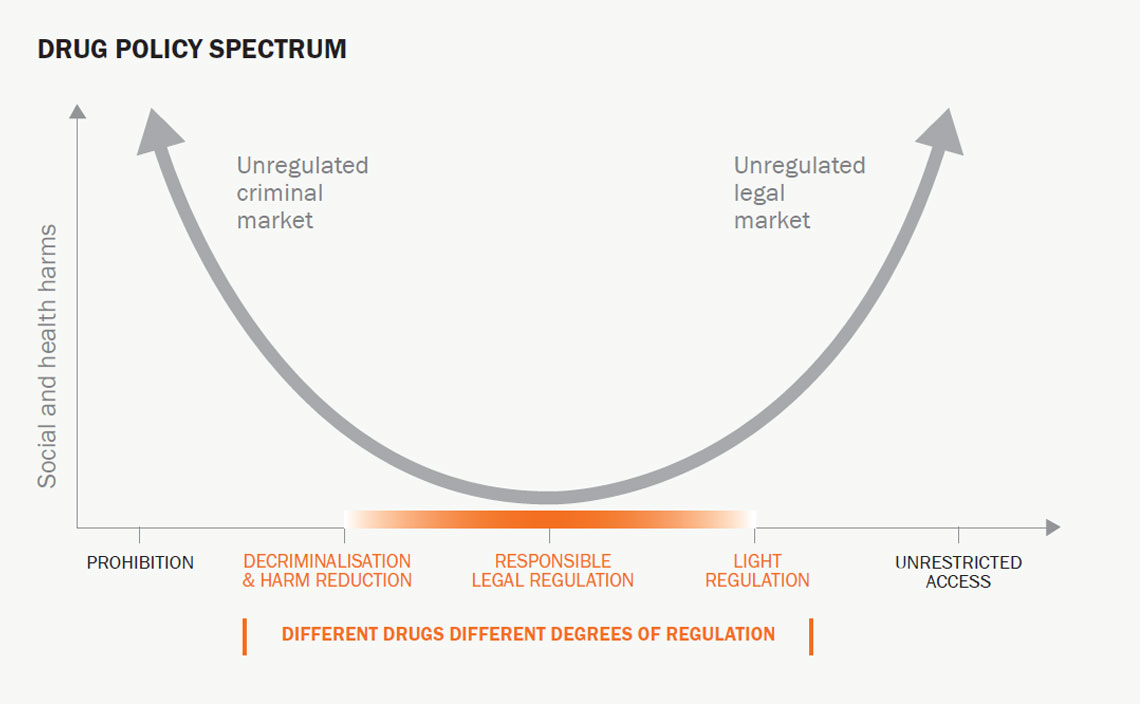

This certainly does not mean open slather or a free commercial market. In an entirely profit-driven market, companies would target heavy users and increase harm from cannabis (as indeed occurs currently). For that reason, we need to regulate any market.

The NZ Drug Foundation’s proposal for a model drug law would start with very strict controls, which could be amended as appropriate over time. We want to avoid making the same mistakes that were made with alcohol and tobacco, where powerful industries with vested interests resist regulatory changes intended to put health before profit. It makes sense to start cautiously and monitor the impacts as we go.

We advocate for a regulated market for cannabis, which keeps health interests central. There is already a regulatory system set out in the Psychoactive Substances Act 2013 that could be modified to accommodate the development of a cannabis market. The purpose of that Act aligns perfectly – it aims to regulate the availability of psychoactive substances to protect health and minimise harm.

We propose that licensed premises would sell only cannabis, cannabis-related paraphernalia and plant seeds. Businesses would be prohibited from selling alcohol and tobacco alongside cannabis to minimise the risk of compounding harms or creating new cannabis markets.

The locations and opening hours of licensed premises would be strictly regulated. There would be no retail outlets near schools, for example. Communities would have a say in whether premises were permitted in their areas.

Workers in cannabis shops would have training in health issues relating to cannabis, such as keeping an eye out for signs of dependency. Only those over 18 would be allowed entry, and all products would be stored securely behind the counter.

From a purely health perspective, setting the age limit at 20 or even higher would be the best option. However, this would create avenues for a black market to flourish, as a large percentage of those who already use cannabis are between the ages of 18 and 20. It makes sense to align the cannabis age with the legal alcohol purchase age and then focus on minimising harm through health interventions.

See our Model Drug Law page for more details.

Drug policy spectrum: Diagram from the Global Commission on Drug Policy. - The alternative to prohibition does not have to be a free commercial market. There is a whole spectrum of different policy options, as shown by this diagram from the Global Commission on Drug Policy.

We do not want to encourage the development of a wide range of cannabis products, as this could encourage new users, especially young people. It would go against public principles to allow THC gummy bears for sale or for people to sell special brownies at farmers’ markets, for example. Therefore, if edible products are to be available, these should be licensed for sale on a case-by-case basis. A licence could only be issued if manufacturers demonstrate a low risk of harm and meet other criteria.

We also want to keep profits in communities and stop Big Cannabis from gaining a stranglehold on the market. We would therefore restrict farm size by keeping each grower below a maximum number of plants. A government body would license all suppliers, but the number of suppliers and amount of product produced would depend on the market. We support supply models that will enable disadvantaged regions to benefit from growing cannabis. This could be done by keeping licensing requirements simple and inexpensive and helping current small-scale suppliers move from the black market into a regulated market – for example, by providing pre-approved packaging and assisting with taxes and forms.

A levy would be taken at the point of sale, with the money collected going back into covering administration costs as well as education, treatment and prevention programmes. Our model also provides for people to grow their own plants. We think three plants per adult, with a maximum of six per household, would be a reasonable number. There is no science to setting a limit on the number of plants allowed. Some jurisdictions – such as Washington State – allow none, while others allow six or more. Our compromise of three plants would allow people to grow enough for their own needs but not so much that a black market would be created.

It is worth noting that, in New Zealand, people are allowed to grow tobacco and brew their own alcohol, but very few people actually do either. We envisage the situation would be the same with cannabis once the novelty of growing plants at home wore off. Restricting advertising is a key way to reduce demand for a product, so we support plain packaging with health warnings, limited shop frontage advertising, no advertising outside licensed venues and no sponsorships or gifts. We don’t envisage seeing The Cannabis Shack netball or rugby team.

We want to avoid the product looking too glamorous and exciting. At the same time, we do not want it to be so standardised that the black market steps in to fill already-existing niche requirements for products. For those reasons, it is important the growers can establish brands by displaying their logos and information identifying the provenance of the cannabis and its effects.

Licensed premises would be required to display public health information prominently, explaining to people how to moderate use and detailing how to access help for drug-use issues.

There would be a limited online market, possibly organised similarly to a Trade Me page. Obviously, there are risks that those under 18 could seek to purchase online, but these can be guarded against by ensuring that the person who accepts the product delivery is the same person named on the credit card used for the purchase.

Another option would be using a RealMe account to prove identity. Even in a legal market, there need to be penalties for not sticking to the rules.

Once again, the Psychoactive Substances Act already provides a good model. This would mean those selling cannabis to people under 18 could be fined up to $5,000, while under 18-year-olds buying cannabis would face fines of up to $500. There would be penalties for manufacturing or selling without a licence and for making misleading licence applications.

The government would control cannabis prices to restrict demand – as it does for alcohol and tobacco. We suggest minimum pricing as well as a regime of levies that would be earmarked to fund treatment services.

We have learned from regulating the tobacco industry that keeping prices high is one of the key ways to reduce use. Cannabis would be taxed according to its potency. Those using higher-potency products are most at risk of harming themselves, so consumption of high potency products would be moderated by higher prices.

The NZ Drug Foundation supports regular reviews of the law to ensure it is working and not having negative health impacts.

As well as improving health and reducing the long-term harm and stigma of convictions, our approach makes economic sense. A Treasury official in 2016 calculated that legalising cannabis would save $400 million a year on drug prohibition enforcement and reap an extra $150 million in tax revenue.

There would be no need for separate laws regulating medical cannabis because the therapeutic use of cannabis would no longer be illegal. Cannabis-based medicines would continue to be available through the pharmaceutical approvals model.

We would like these medicines to be easier to access and fully subsidised.

See our Model Drug Law page for more details.

What’s in it for Māori?

An important element of our model law is Māori equity. Te Tiriti o Waitangi provides guarantees to Māori about their status and treatment.

The disproportionate drug prosecution and conviction rates for Māori – who comprised 41 percent of those given jail terms for drug offences between 2010 and 2014 – is discriminatory. Among cannabis users, 3.4 percent of Māori , compared with 1.9 per cent of others, reported legal problems from their cannabis use in the past 12 months.

We believe the model law will benefit Māori by reducing health harms from drug use and drastically reducing the number of drug convictions. Equity could actively be promoted by ensuring Māori experience any economic benefits of law changes.

In the United States, indigenous American tribes from California to New York legalised cannabis in their tribal areas in 2015, and a number of tribes began tribal cannabis-growing operations. We are actively seeking Māori/iwi feedback on this proposal to explore whether there is similar potential for Māori communities in New Zealand.

Eliminating harms

We are very realistic about our proposals. Smarter drug regulation cannot by itself eliminate drug harm. Reform needs to be accompanied by upscaled harm prevention. We need effective education, strong drug harm prevention standards, better access to treatment and drug early-warning information systems. Portugal’s success with its decriminalisation policies to a large extent rests on the fact it combined new drug laws with a hefty investment in prevention, education and treatment.

We are calling for a doubling of investment in addiction treatment and support services to eliminate waiting lists. The $350 million spent every year on drug-related issues should be targeted away from enforcement and into treatment, support and prevention. In the past year, around 50,000 people wanted help to reduce their alcohol or drug use but did not receive this support. At present, we only spend 3 percent of the total health budget on addiction services, and this needs to increase. We would also like to see increased spending on community-based and whänau-centred services, including those that focus on young people.

Low-threshold approaches such as online and self-help options should be made available, and there should be a government-funded destigmatisation campaign to reduce negative public perceptions of people who use or depend on drugs or who are in recovery from drug use. Likewise, those in prison should have much better access to drug and alcohol treatment, both in jail and after their release.

The NZ Drug Foundation also supports helping young people remain in education by strengthening supportive school cultures to reduce disengagement and exclusion resulting from drug or alcohol use.

See our Model Drug Law page for more details.

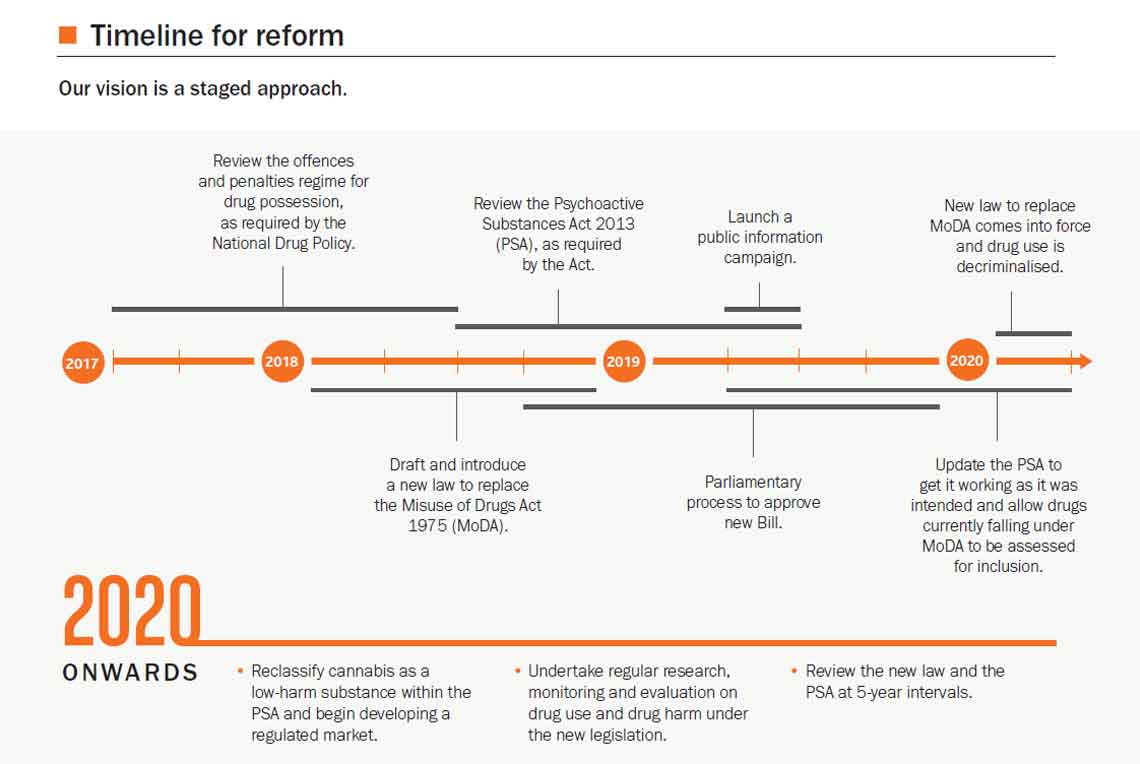

Our timeline for reform - The NZ Drug Foundation's timeline for reform takes us to 2020 and beyond.

Where to from here?

We see a staged approach to bringing in the model law. A review of the offences and penalties for drug use and possession required by the National Drug Policy is due to start in the second half of this year, which makes now an ideal time to start working on introducing a Portuguese-style model of decriminalisation here.

To do this, we propose the government drafts a new drugs Bill in 2018 to be administered by the Ministry of Health. A public information campaign on the Bill could take place in 2019 prior to submissions being called by select committee. We would like to see the new law in force by 1 February 2020.

Meanwhile, the Psychoactive Substances Act is up for review in 2018. This is therefore the right time to reform it, both to make it work as it was intended and with an eye to bringing the regulation of cannabis into the revised Act. After 2020, cannabis could be removed from what is currently the Misuse of Drugs Act 1975 and reclassified as a low-harm substance falling under the Psychoactive Substances Act.

This would enable a regulated market to be developed. Five-yearly reviews of the Psychoactive Substances Act and the new drugs law would be built into the legislation. The War on Drugs has been raging for more than four decades. In that time, it has consumed billions of dollars and failed utterly to cure the harms it seeks to address.

In May, the Police admitted that this country’s meth problem was getting worse and that their battle against it had achieved “no visible impact”. In fact, in 2016, the Police seized more than twice as much meth as in any other year, but this had no impact on the drug’s availability.

We know our proposals are likely to cause controversy and concern. But it is time for a new, evidence-based approach that will actually curtail the harms New Zealand must urgently address.

Tough talk on drugs might sound good, but it is achieving nothing.

Download a copy of the model drug law below, or Contact Us for a paper copy.

Recent news

Reflections from the 2024 UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs

Executive Director Sarah Helm reflects on this year's global drug conference

What can we learn from Australia’s free naloxone scheme?

As harm reduction advocates in Aotearoa push for better naloxone access, we look for lessons across the ditch.

A new approach to reporting on drug data

We've launched a new tool to help you find the latest drug data and changed how we report throughout the year.