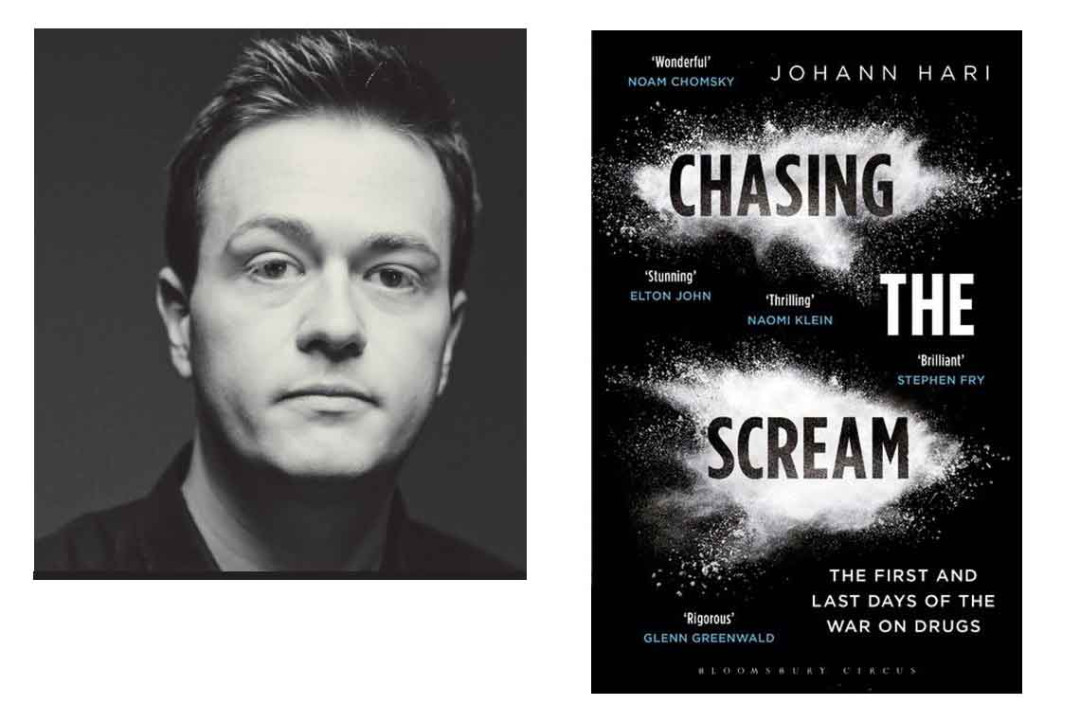

Q&A: Johann Hari

British journalist Johann Hari’s book Chasing the Scream: The First and Last Days of the War on Drugs (2015) is still being widely read around the globe. Q&A asked the award-winning author for a quick update.

Q Remind us what you covered in Chasing the Scream.

A One of my earliest memories is trying to wake up one of my relatives and not being able to. I wanted to understand why we have a War on Drugs and what the alternatives are, so I went on a 30,000 mile journey to over 17 different countries and realised that everything we think we know about drugs, about addiction and about the War on Drugs is wrong.

Q What has been the response since the book was published?

A What has been most moving is hearing how many people – either with an addiction problem or who have someone they love who has an addiction problem – felt that the different frames for talking about addiction has helped them in their lives. Hearing it explained that the addiction is an understandable reaction to human distress and that the solution is to deal with the underlying reasons why they’re distressed, that really helps people. I think it also helps the 90% of people who use current illegal drugs who don’t become addicted to have a story for themselves, right? Because they are, like, everyone kept telling me, “Oh my god, you must not use this drug, you’re going to become addicted,” but they never have become addicted.

The core of addiction is about not wanting to be present in your life because your life is too painful a place to be. We talk all the time in addiction about individual recovery, and there’s real value in that, but we need to talk much more about social recovery. Something’s gone wrong with us, not just as individuals but as a group. During the run-up to the US election last year, I spent time in Ohio – the former Rust Belt. When you talk to people who’ve lost everything that gives life meaning, they are profoundly disoriented. They have super-high addiction rates and super-high suicide rates. The addiction crisis is one manifestation of that. On top of that, you have a terrible drug policy that makes the problem worse by punishing people.

Q Should we still keep an eye on Portugal?

A The Portuguese experiment is really remarkable, which is why I talk so much about it in the book. When you make the argument for reform, people often start asking perfectly reasonable questions like, “How would that work?”, “What does that mean?” And very often, people get diverted into a weirdly abstract argument, like we’re a philosophy seminar. And I always say to people, “No, no. This isn’t an abstract question.”

I’ve been to the places that have the toughest possible policies. I’ve been to Vietnam where they make drug users go into gulags. I’ve been to Arizona where people convicted of drug crime wear t-shirts saying “I was a drug addict” while members of the public mock them. And I’ve been to the places that have the most compassionate drug policies, and we can see how they work.

From these different experiments and methods, the results are very, very clear. Irrespective of what you think of the ethics of them, the Drug War produces more violence and more addiction and does not solve the problems of drug use.

Compassionate policies are not a magic bullet – there are still problems – but everywhere they move beyond the Drug War, they’ve seen a significant reduction in these problems. We have to look at the evidence. Policies based on shame and stigma and transferring drugs to criminals don’t work. Policies based on love and compassion and regulating the drug market have radically better success rates.

Q What is happening in places like Colorado?

A No one should overstate our knowledge of the results, but there are a few things we do know. Since cannabis was legalised in Colorado, support has significantly increased for legal cannabis after people have seen it in practice. Teenage drug use has remained steady and remains lower than the US national average, significant sums of money have been raised in taxation for good purposes and there appears to have not been a significant increase in problems associated with cannabis.

We’ve also learned some negative lessons. I don’t think commercialised packaged edibles are a good idea, especially not ones with little cartoon characters on them. But the good thing about a legal regulated market is we can change the regulations. Let me stress again, the Colorado option is radically better than what we have now. Even so, I would prefer the Spanish system of not-for-profit cooperatives that can’t advertise and don’t promote and don’t go down a highly commercialised route.

Q Looking forward, where are things heading?

A Every democratic politician in the world is constantly making calculations: “If I take this decision, how much praise will I get and how much shit will I get?” At the moment, if you do the right thing on drug policy, you get a little bit of praise and a whole lot of shit. But we can change that balance of calculations.

I’ve seen that balance of calculations change in my lifetime on gay marriage. I didn’t even hear the concept of gay marriage until I was about 19, and look how widely accepted it is now. I went to Colorado, and I saw the first legal cannabis shop open. I thought, this is the first act in the end of the Drug War. And it’s up to us how quickly we tear it down.

RESOURCE: chasingthescream.com

Recent news

Reflections from the 2024 UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs

Executive Director Sarah Helm reflects on this year's global drug conference

What can we learn from Australia’s free naloxone scheme?

As harm reduction advocates in Aotearoa push for better naloxone access, we look for lessons across the ditch.

A new approach to reporting on drug data

We've launched a new tool to help you find the latest drug data and changed how we report throughout the year.