How well are pre-charge warnings working?

Pre-charge warnings have quietly become a valuable new tool in the policing tool box and an effective way of getting minor crime out of an overloaded court system. But after four years, the greatest strength of the precharge warning has also become its biggest weakness. Sofia Wenborn reports.

When New Zealand Police were told to give the justice system a break and reduce the number of prosecutions appearing in court, a change in tactics was required. In 2010, the government gave Police two targets. Recorded crime had to reduce by 13 percent, and the number of non-traffic cases appearing in court had to drop by 19 percent. The deadline was 2014/15.

Those are fairly high targets and human behaviour isn’t such that crime just disappears because we want it to. However, the way Police deal with some crimes can make them almost disappear.

Policing Excellence was the initiative that followed. The language around it is that of crime prevention and intelligenceled policing. In practice, it means more discretion – in particular, discretion not to prosecute so many people for minor crimes.

Pre-charge warnings are one of the new tools in the kit. They slot in between the informal slap on the hand and the Police diversion scheme, where an offender is still prosecuted in court but the charge is withdrawn by Police if the offender admits their guilt and complies with some conditions.

The pre-charge warning sees an offender brought into the Police station for processing but before a charge is laid, the arresting officer, together with a supervisor, use their discretion to send the offender off with a written warning. It’s recorded but, importantly, it doesn’t appear on someone’s criminal record.

Police don’t have to prepare the paperwork that goes with laying a criminal charge; nor do they have to put in the hours required to prepare a prosecution for court.

In August this year, 1,710 offences were dealt with by handing out a precharge warning, and since their introduction four years ago, Police say 37,000 hours of Police time have been freed up.

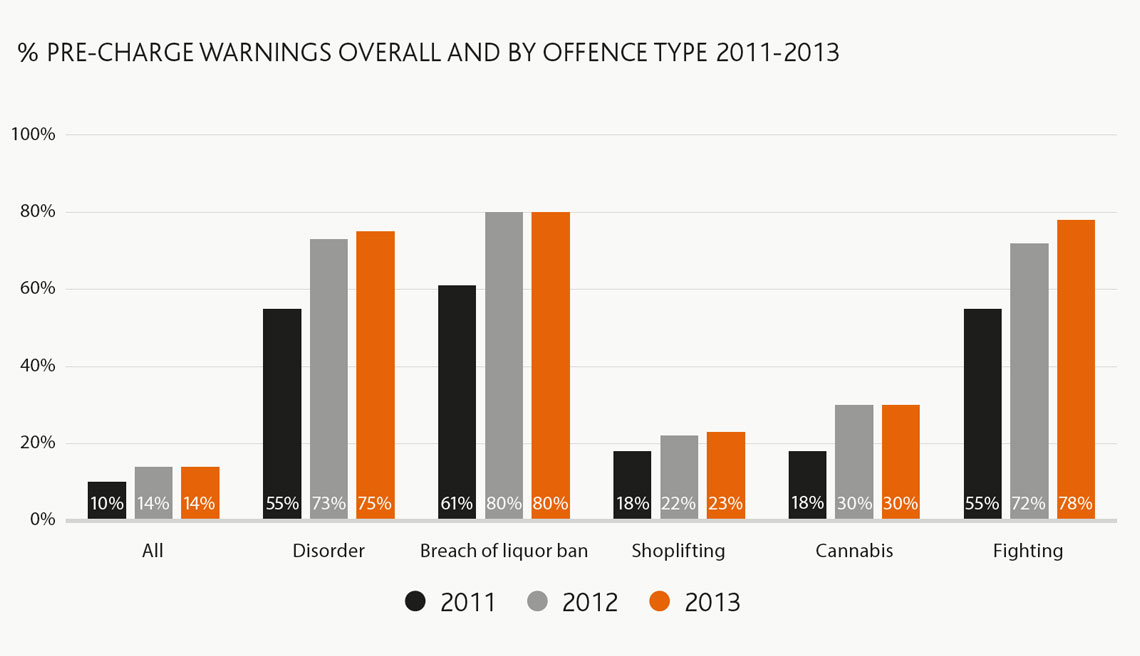

More pre-charge warnings in 2013 than 2011 for all types of offence

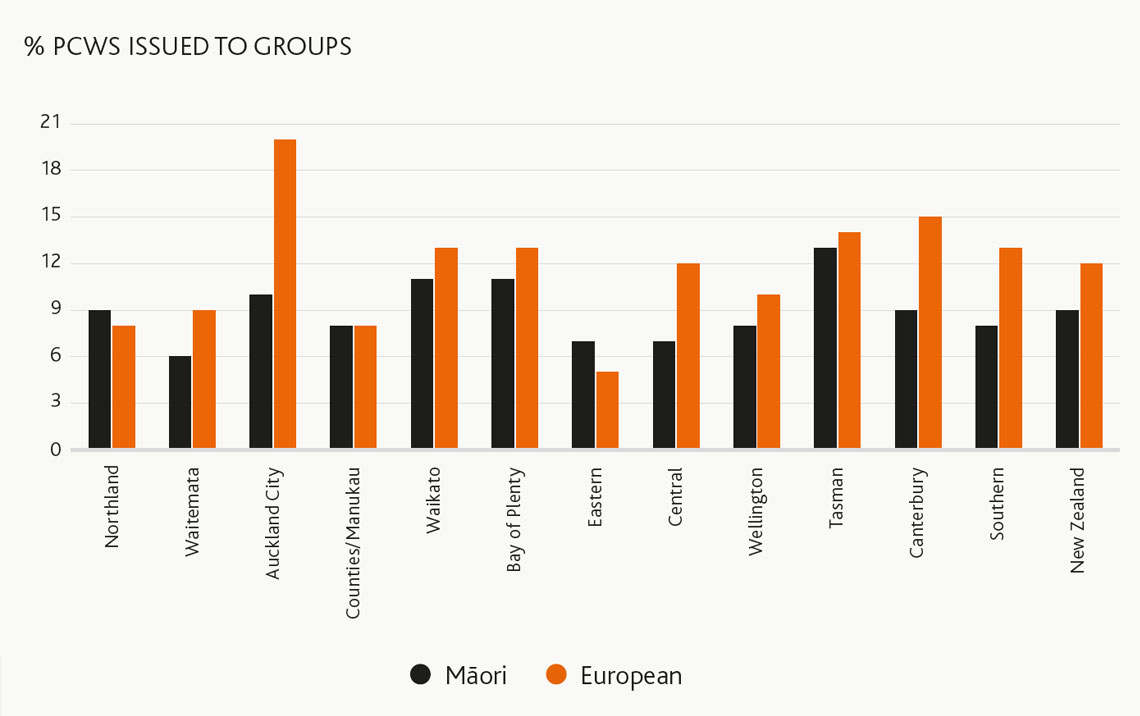

Smaller percentage of pcws issued to Māori by region except in Northland (more) and Counties/Manakau (same)

Deputy Chief Executive Māori, Superintendent Wally Haumaha says, “It’s an option which still enables staff to prevent harm within their communities without creating an extra burden on the system.”

Cynical minds may suggest it’s shuffling deck chairs, and to some extent it is. Rethinking Crime and Punishment’s Kim Workman says pre-charge warnings certainly look good on paper.

“But they’re also a good idea because the longer you keep people from the formal criminal justice system, the less likely they are to become serial criminal offenders.”

Offenders aren’t the only ones glad to escape conviction. Police are happy to escape the paperwork on files that frequently went nowhere or had no merit. An evaluation report carried out six months into the scheme found wideranging support. As one officer said, “Less time spent preparing files for court means more time spent on the road,” which is certain to make taxpayers happy as well.

There are some rules around the pre-charge warning, of course. They’re designed for those minor crimes that are considered ‘victimless’. By far and away the largest number are handed out for alcohol-related offences like breaching a liquor ban or disorderly behaviour.

Crimes that carry a penalty of no more than six months in prison are the only ones eligible. That means minor shoplifting is also on the list and, to a small degree, possession of cannabis. And as time has gone on, Police are choosing to resolve more offences in all categories with a pre-charge warning.

Alcohol remains the easiest offence to deal with like this. As one senior justice expert says, minor charges are generally a tool for Police to deal with difficult situations. When alcohol is causing a problem, Police just want the ability to remove the person from the situation to diffuse tension. The outcome is usually a conviction and a pretty small fine.

Police officers spoken to during the evaluation process said pre-charge warnings gave them the ability simply to take the offender back to the station and let them cool off or sober up. Most were shame faced enough to apologise. What additional use, then, is the court process?

And how do Police rationalise a precharge warning for an illicit substance such as cannabis?

In practice, they do have a harder time. While 75–80 percent of liquor offences are resolved with a warning, only 30 percent of cannabis possession offences are dealt with the same way. If you’re caught with cannabis, you’re probably going to court, but the stats don’t lie. Police are certainly showing signs of becoming more lenient.

“A pre-charge warning still holds an offender to account,” says Haumaha, “and the intent is that it will act as a deterrent from further offending behaviour. The offence committed is still treated seriously and is recorded in official statistics.”

Workman, however, would like to see a little more consistency with regard to cannabis and the pre-charge warning.

“I think the general rule should be that amounts sufficient for personal consumption almost inevitably get a warning. And I fail to see the difference between one person being warned for possession and another being charged.”

Auckland defence lawyer Ron Mansfield says he still sees people going through court charged just with possession of cannabis.

“As to why that couldn’t be a fine and a warning, I don’t know,” he says.

“But as a result of a search, people are generally charged because Police want to justify the search action. If it’s just seeing someone on the road with a joint, the Police might throw it away. I guarantee the number of people found with cannabis and not charged is higher and just dealt with informally.”

Police aren’t quite ready to acknowledge that.

“To my knowledge, this is not a common practice. Police practice is to go through a proper process of a pre-charge warning,” says Haumaha.

That proper process certainly has reduced the burden on the court system.

Mansfield agrees there are fewer minor charges going through the Auckland District Court now, and for that he’s grateful.

“A conviction for low-level offending has quite severe ramifications, and you don’t appreciate that till you get one. You’re creating people who are unemployable and people who can’t advance in life. When you think about the forms you complete over a year, whenever you apply for a job, insurance, bank accounts or when you travel to a certain jurisdiction where you tick the box that you have no previous convictions, they have to disclose that conviction and hope someone will take the time to reassess them as a whole person, not just judge them for that conviction.”

In particular, Mansfield says, it used to concern him most at Counties Manukau District Court. “The number of young people going through that court on very minor charges and getting a conviction and a fine they probably couldn’t pay, then trying to get on with life from there in a struggling community, that makes their struggle even worse.” His concern about specific

communities is justified because, as encouraging as the pre-charge warning system appears, there are alarm bells. And sadly, they are the same alarm bells we’ve become all too used to hearing. Some people are more likely to receive a pre-charge warning than others, and no surprises here – it’s Pākehā. Police were sharp to the possibilities of racial discrepancies before the scheme was introduced, and six months in to the system, their fears were already being realised. Four years later, and the figures still show that Māori are less likely to receive a pre-charge warning.

Police say there are alternative processes in place for dealing with low-level offending by Māori, such as the Iwi Justice Panel.

“This initiative includes panels of vetted and trained community representatives who set conditions to help reduce and repair the damage and harm caused by certain offenders, rather than charge and prosecution,” says Haumaha.

Nevertheless, Police are aware of the discrepancies, and every month, all pre- charge warnings are reviewed.

“Districts are advised of cases where eligible offenders were not issued a pre-charge warning. Districts will then undertake an audit and assess cases to ensure the policy is being followed equitably.”

Workman says it all looks very familiar.

“It’s very similar to a piece of research I did in 1998 for the Police when we looked at the issue of diversion. They were concerned the number of Māori offenders getting diversion was too low, and they wanted to find out why. Our research showed that Police had the belief if someone had committed a previous minor offence they were not entitled to be diverted. Māori tend to be convicted of a greater number of minor offences than non-Māori because Māori tend to be stopped and questioned more often, tend to have the car searched more often, tend to be searched for cannabis more often. So a lot of them weren’t being diverted for very minor offences, but that policy was non-existent really. It was in the minds of Police officers, but there was no policy around to confirm it.”

Now, the pre-charge warning system seems to be perpetuating that cycle.

But if it’s something Police have been aware of and concerned about for so long, why hasn’t there been any headway made?

The problem lies with the very thing that makes pre-charge warnings so effective – discretion.

A Police officer’s discretion is a double-edged sword. Police will use their discretion not to prosecute if the offender is regarded as low risk, but that carries socioeconomic and ethnic undertones.

As a senior justice expert says, “Māori are more likely to have a criminal record, less likely to be respectful of Police so more likely to be lippy. The officer is therefore less inclined to be lenient. It’s not a criticism of Police, it’s just how it works. Police use stereotypes to work out who they need to take action against, and that’s a source of bias and discrimination. Stereotypes are self-fulfilling prophecies; they always have some basis in experience, but they’re also discriminatory.”

So how do you stop behaviour that is in some way inherent to human nature but creates inequality? The answer may lie in a paradox. Discretion needs set guidelines.

Three years, ago this is exactly what the Law Commission explored in its review of the Misuse of Drugs Act. It noted that Police discretion when dealing with cannabis possession led to a more appropriate response, but it also created an opportunity for unfairness and discrimination. To overcome that, the Law Commission suggested a mandatory cautioning scheme with a clear process – three cautions followed by either a referral to drug treatment or prosecution.

A senior justice official says the pre-charge warning system would be improved by this kind of structure. It wouldn’t necessarily need to be written into law, but there would be a prescriptive set of guidelines that Police had to adhere to.

Workman agrees. “Police have avoided developing policies of that kind, and I think it’s time they did. Police are conscious of it, but when people like [Justice Minister] Anne Tolley deny the existence of institutional racism, nobody is forced to address it. We need to have policies around ethnic profiling, we need to have policies around the use of discretion in relation to finding people in possession of cannabis. There needs to be clear guidelines about stopping people.” Police themselves are open to improvements.

“The scheme will continue to be monitored and reviewed to ensure that it is being implemented correctly, and an expansion to a broader range of offending may be considered. It is too early to say what form this expansion will look like and whether or not legislative change will be required,” says Haumaha.

Māori are more likely to have a criminal record, less likely to be respectful of Police so more likely to be lippy. The officer is therefore less inclined to be lenient. Mansfield welcomes that and suggests offences carrying a prison term of up to a year could be considered.

“Low-level dishonesty, property damage, low-level assaults such as common assault, like a fight at a party. It doesn’t mean they couldn’t lay a charge, it would just mean that, in appropriate circumstances, they could warn.”

In the meantime, Huamaha is happy pre-charge warnings are meeting their purpose.

“People who commit low-level offences and are unlikely to reoffend are not being caught up in the criminal justice system. There have been 77,000 pre-charge warnings issued to date, which has resulted in 65,000 people not going through the court process.”

It’s rare that Police and criminal defence lawyers agree, but on this, there is harmony. Because, as Mansfield points out, there but for the grace of God ….

“In reality, that low-level offending is committed by a much wider group within the community. Being drunk and disorderly or carrying a bottle of booze through town, or trying cannabis – not many people get through their youth without doing something like that, but most are fortunate enough not to be arrested. If you are unfortunate enough to be caught experimenting with life a wee bit, you end up with a conviction that’s with you for a long time.”

Recent news

Reflections from the 2024 UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs

Executive Director Sarah Helm reflects on this year's global drug conference

What can we learn from Australia’s free naloxone scheme?

As harm reduction advocates in Aotearoa push for better naloxone access, we look for lessons across the ditch.

A new approach to reporting on drug data

We've launched a new tool to help you find the latest drug data and changed how we report throughout the year.