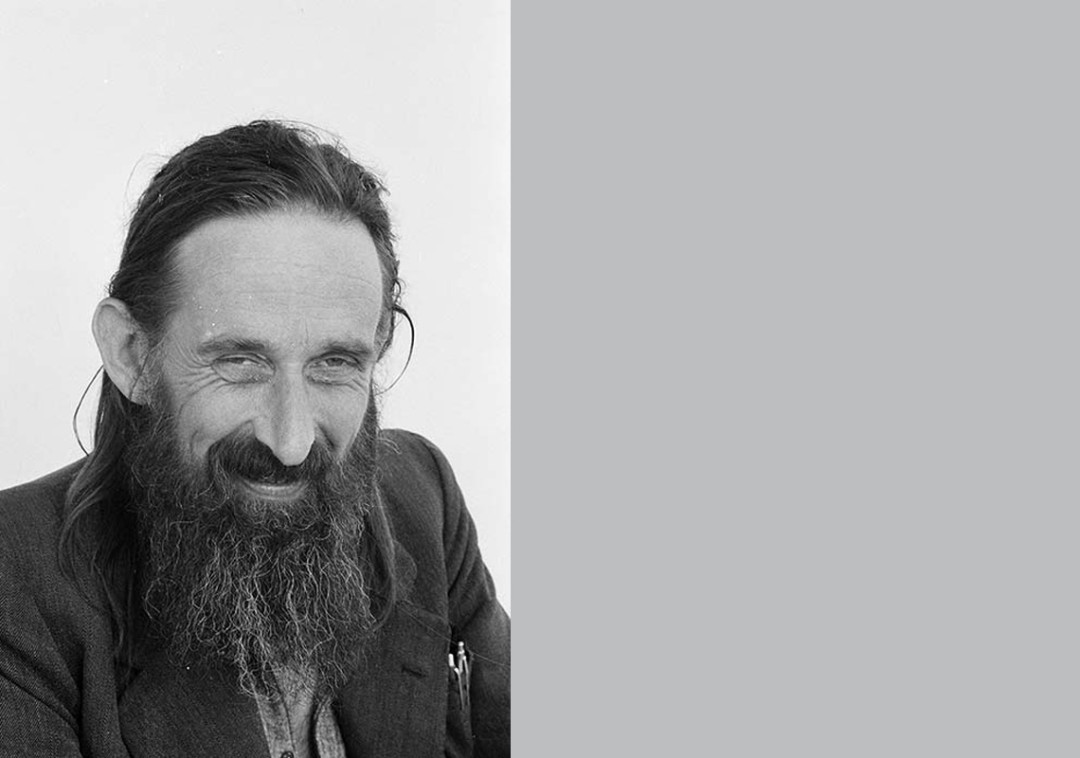

Drug history: James K Baxter: poetry and political influence

Redmer Yska begins a new series looking at drugs and history in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Hemi Baxter’s place at number 7 Boyle Crescent in the late 1960s was just another rickety wooden villa set amidst the rundown – almost slum – housing stock then popular with university students and now probably worth millions. By 1968, the ‘squats’ of Grafton housed many of the free spirits embroiled in contemporary issues: the Vietnam War, apartheid, anti-materialism – and consciousness expansion.

Invercargill Mayor Tim Shadbolt, then a student firebrand, lived in nearby Gibraltar Crescent. He chose number 5 Boyle Crescent to host the first meeting of the Day-Glo Activists Cultural Liberation Front. The street was also notorious as a place where illegal drugs were available at a time when experimental use was on the rise. The first local arrest for LSD occurred at number 9 in July 1967.

Then, on 26 June 1968, a 17-year-old Boyle Crescent resident named Phillip Sharples died in a squalid room after injecting heroin. The tragedy drew only muted headlines, but behind the scenes, health and law enforcement authorities were appalled, and the full gaze of officialdom turned to the tiny Grafton street.

What was most shocking to officials was that a middle class European had been fatally caught up in what they saw as a sinister backstreet drug culture only identified with elderly Chinese. Not until 1964 did local Police stop recording Chinese opium and heroin arrests separately.

The Sharples death also occurred as a government committee sat down in Wellington to examine a growing outbreak of drug use. National drug offences including cannabis, LSD and heroin had jumped from 10 in 1965 to an alarming 50 by 1967. Health

Department Deputy Director Dr Geoffrey Blake-Palmer, a former mental hospital superintendent, chaired the committee. Other members included Oakley Mental Hospital head Dr Patrick Savage and then Assistant Police Commissioner Bob Walton.

The committee was asked to take a “careful and dispassionate” look at drug use, but its early energies were diverted by the Sharples fatality. Records show that a telex marked ‘urgent and confidential’ flew between Auckland’s CIB boss and Assistant Commissioner Walton. It talked of an outbreak of abuse involving “literally hundreds of people in Auckland”.

Police Department records from 1968 show that the authorities had already been watching Boyle Crescent closely. In an internal memo, Detective Inspector Perry from the Auckland Vice Squad called it “an address occupied by and frequented by known drug users”.

As part of subsequent field studies, Dr Blake-Palmer and committee members toured parts of Auckland with detectives. The chairman prioritised a visit to Boyle Crescent and chatted with Baxter. Committee records reveal how much the advanced disrepair of the houses, some even lacking front doors, disturbed officials.

Blake-Palmer wrote: “Although the buildings were structurally sound, the condition of the rooms in which these people were living, two of them reputed to be university students, was appalling. There was a complete absence of even nominal standards of cleanliness. Garbage was stacked in one corner and unwashed clothing lay where it fell.”

At Boyle Crescent, meanwhile, Baxter was providing accommodation and support to the country’s first wave of drug casualties. An active member of AA since the 1950s, the poet believed that, rather than be sent to prison – or, worse, mental hospitals, as was the norm – drug users like Sharples needed care and support.

Baxter’s biographer Frank McKay says the poet tried to ensure that everybody who came to number 7 – from street kids, to full-time drug users to middle class dropouts – was treated with kindness and aroha. Baxter himself wrote of the inclusive nature of the community: “One long-standing user of drugs, a Mäori woman, has come off them. One man, a user of amphetamines, who has been several times in the bin, has improved a great deal. I put my arms round these people and talk to them. They are often like children lost in the dark.”

During 1969, Baxter set up pioneering meetings of Narcotics Anonymous (NA), an organisation based along on AA lines, where people with addiction help each other stay off drugs. Because of the Police attention, the people who needed the meetings mostly stayed away from the sessions. NA was resurrected in 1982 and remains nationally active.

Exhausted from his efforts, Baxter then left Auckland for Jerusalem on the banks of the Wanganui River. But the visit to Boyle Crescent had registered with the committee as it continued its deliberations.

Later that year, Dr Blake-Palmer approached Baxter as someone who could help articulate what the young were thinking. A memorable letter seeking his whereabouts was dispatched to the Medical Officer of Health in Wanganui. “The Committee wishes to write to James K Baxter who passed through Wanganui late last month on his way to plant kumaras in Jerusalem.”

Baxter seized the opportunity to contribute. His handwritten nine-page submission talked of a “rebellious” subculture with its own customs, music, religious preferences and nuances of feeling. “I wish neither to defend or attack it. I wish only to point out that, as in the international sphere, ethnocentric prejudices are useless and lead only to greater tension and misunderstanding.”

He addressed the Police’s emotional fear and contempt for the younger vagrant population of drug users. “Accidental issues – cleanliness of houses and people, unusual dress and speech, regularity of employment, de facto sexual relationships, hair length and so on – play a vital part in the police view of drug users, and the view of a good many doctors. This leads to the blind alley of a battle over lifestyles.”

The work of the Blake-Palmer review, which sat sporadically between 1968 and 1973 and published two reports, culminated in the Misuse of Drugs Act 1975. In 1971, Baxter made a second substantive contribution, meeting with the committee in Wellington on 14 and 15 October.

When the committee finally reported back in 1973, the 250-page document contained a whiff of Baxter philosophy, recommending a new emphasis on treatment over punishment for drug use. The poet never got to read the report: he’d died the previous year, aged 46.

Recent news

Reflections from the 2024 UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs

Executive Director Sarah Helm reflects on this year's global drug conference

What can we learn from Australia’s free naloxone scheme?

As harm reduction advocates in Aotearoa push for better naloxone access, we look for lessons across the ditch.

A new approach to reporting on drug data

We've launched a new tool to help you find the latest drug data and changed how we report throughout the year.