A defence of death

New Zealand’s Big Tobacco boys have come out with a co-ordinated attack against proposed plain packaging law. But why, when their industry is one of the most reviled, are they spending big bucks in a defence of death? David Slack investigates.

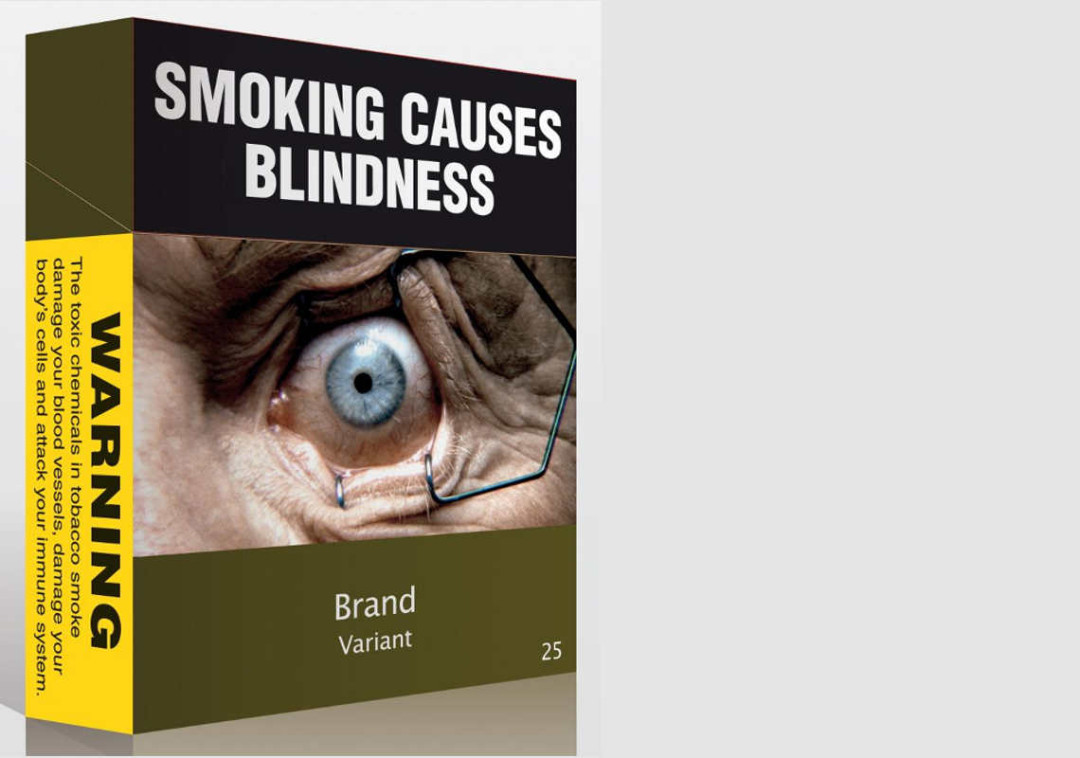

Never let it be said that New Zealand rushes headlong into things. It was 1989 when Ministry of Health officials first floated the idea of putting cigarettes in plain packages – 23 years on, that day might soon be upon us. From December, cigarette companies in Australia will be required to sell their cigarettes in dark brown packs with no logo. Where Australia goes, we go. Where she takes a stand, so might we. The government has said it supports the idea in principle. A round of public consultation has closed; a Bill and a select committee appear likely.

It’s been a long time since the tobacco industry stopped denying the deadly links between smoking and fatal illness. But the right of the individual to do harm to him or herself is precious, and Big Tobacco has been taking its well funded voice to the barricades as it fights a determined, if rearguard, action in defence of the freedom of its customers to buy a lethal product.

The battle for the brands began in New Zealand with a surprisingly frontfooted stance, with Nick Booth – the spokesperson for British American Tobacco (BATNZ) – chatting to Kathryn Ryan on Radio New Zealand and Chris Bishop of Philip Morris International joining Sunday morning’s Q+A show on TVNZ to deplore the notion of a plain-pack regime. With an openness not seen since the American Medical Association endorsed tobacco, their message was unambiguous: smoking might be deadly, but the rights of adults to a deadly act of pleasure ought not to be unreasonably denied. Moreover, honest businesses stood to be deprived of their intellectual property, New Zealand stood to have its international reputation tarnished and your children might soon be buying their tobacco from gang members.

The big gun, however, was to be a marketing campaign that would be variously observed to be “wasting money”, “a battle for the next generation of potential smokers” and “illogical”. Herald columnist Toby Manhire wrote of it: “I wouldn’t say I’m addicted. I could give up any time. But by God, those Agree/Disagree ads are transfixing.”

The campaign, which can be beheld at www.agreedisagree.co.nz, has been nothing if not arresting, with full-page colour print ads, radio ads and TV commercials proposing such forthright appeals to freedom-loving New Zealanders as: “If I create it, I should own it.”

No campaign warning of dire consequences comes without a slippery slope. “Plain packaging, once introduced, is unlikely to be limited to tobacco products,” BATNZ said. “Which products will be next?” You could not fault the campaign for its commitment to substantive argument. “Our branding is property – intellectual property – and the government shouldn’t be able to take that away,” they said. “Plain packaging would infringe New Zealand’s international obligations, damage its strong trading reputation and expose the country to legal challenges,” they warned. “There’s no proof that plain packaging would reduce smoking rates in New Zealand,” they added, with entirely straight faces.

Intellectually, it is quite the acrobatic challenge. The argumentative contortions you must go through rest heavily on the concept of the free-willed person making an adult choice. It can be difficult to watch the manoeuvre without wondering how long it will be before you see a well informed adult fall from the intellectual high wire of his own free will.

Carrick Graham, a public relations consultant who once worked for BATNZ, still has skin in this game by way of client the New Zealand Association of Convenience Stores. He will gladly step you through the numbers: contribution of tobacco sales to turnover – sometimes as high as a third; cost to business of delays having to fetch cigarettes from behind lock and key – significant.

He is happy to step out onto the wire. He views this debate principally through the prism of the undue influence and role of the state. “My biggest beef is that New Zealanders aren’t taking responsibility for their own actions.”

He champions the right of a guy in Tokoroa to enjoy a smoke at the pub at the end of a hard day’s work in the forest. That smoker in Tokoroa knows the risk he’s running, but he also likes the pleasure of it, and the state shouldn’t be telling him he can’t, Graham believes. That guy loves his smoke, he says, and he imagines he, and the rest of the 23 percent of New Zealanders who smoke, would be in full support of the Agree/Disagree campaign.

Don’t try to argue it’s an unfair fight, this smoking addiction business, with a vulnerable teenager pitted against the weight of a multinational marketing machine; Graham’s not buying it. When did you last see any sort of advertising in this country for cigarettes, he asks? “No tobacco company was standing next to you at that party when you decided to have that first smoke.”

But even if we accept that this is a bargain freely made – if soon regretted – by free-thinking New Zealanders, how likely is it that they will support a relatively abstract argument about intellectual property rights? Graham cites those 23 percent. But will they care very much? Actually, he says, even if they don’t, the point of the campaign is principally to raise some noise. Sufficient noise may cause the government to have misgivings. It may cause them to ponder the ramifications of their policy.

PR strategist and political pundit Matthew Hooton concurs. He thinks the campaign is well conceived; it cleverly pushes sensitive buttons such as trans-Tasman rivalry. So yes, it will raise noise.

But he doubts the noise will, in the end, be sufficiently troubling to change policy. It’s not sufficiently aggressive. And it’s open ended. “In my experience, they only work if you’re really aggressive.” He recalls two campaigns – forestry, “where they really got to their voter base”, and vehicle importation, where the noise and the grief were sufficiently profound for the government to yield. “It has to be sufficient for the government to want to pay some policy sacrifice just to make the pain go away.” What you’re seeing at the moment is about as noisy as it will get, he says. That’s the way large organisations do things, he says. They won’t push any harder.

When the Health Minister declares the campaign a waste of money, it would seem a reasonable bet the law will pass. Hooton expects so. Carrick Graham, too, can see the months ahead playing out that way. But he notes the backdrop of international legal challenges. Australia’s policy is being challenged in the World Trade Organisation. Hooton doubts the tobacco industry will prevail in any international tribunal. They may have standing, but they lack suasion. To win in that forum, he believes, you really need to be a sovereign nation. He doubts that “even the US” would be interested in championing the cause.

In the face of such long odds, why persist? “Big Tobacco,” Hooton says, “is always concerned about red tape. It sees regulations spreading like cancer around the world.” It sees tape, it chases it down, almost by reflex.

Is this the smartest use of all that time and money? His advice is clear and forthright. His advice “in purely commercial terms” would be expand in China and India where growth prospects are vast (“Smokers there are predominantly male – so you would target women”) and take the brands that will, he predicts, be slowly and surely crippled in first world economies and remake them for a changed landscape. A brand like Rothmans or Benson & Hedges has undeniable value, he says, so why not adapt rather than resist? He notes the Dunhill brand is as well recognised for its high-value branded apparel. He imagines a brand like Marlboro could manage a transformation into, say, a clothing line in the style of RM Williams.

It’s not easy to see the government capitulating on this issue. Research published in early October by Otago University’s marketing department showed more than two-thirds of respondents to a survey supported plain packaging. Support was expected to grow. Legislation for smoke-free bars and restaurants in 2003 was initially supported by about 35 percent of people; now, more than 80 percent of New Zealanders support it, Professor Janet Hoek said. That hard-working smoker in Tokoroa will probably be tapping open a plain packet a year or two from now.

Carrick Graham, for his part, simply asks: where is the evidence it will work? He avers that the Ministry of Health mounts many actions but can prove the efficacy of no individual measure. Pressed on what he might do if he had their job, he proposes tobacco without the smoke. “The smoke’s where all the harm comes from.” He cites Scandinavia where a modern form of snuff is all the rage. It gets you your nicotine fix without any (depending on which research you read) harmful elements. He wonders sardonically, though, how much his man in Tokoroa would enjoy it.

Big Tobacco’s plain response

The spokesperson for Philip Morris, Christopher Bishop, responds to questions about the anti-plain packaging campaign.

David: Do you think, given the Otago Uni research showing such wide support for plain packaging that you can talk the government out of plain packaging?

Christopher: The authors of the Otago study and opinion poll admit that their results do not “demonstrate that plain packaging would reduce smoking prevalence”. In fact, they failed even to examine this fundamental question: would plain packaging prevent people from taking up smoking or make people quit?

Real-world experience undermines arguments that plain packaging would reduce consumption. For example, the authors used the brand Basic, which is not available in New Zealand, as a proxy for plain packs. Unsurprisingly, they found that “virtually the only attributes associated with Basic were ‘plain’ and ‘budget’.” Despite people’s low opinion of it, Basic still managed to become the fourth most popular cigarette brand among US smokers aged 26 or older despite competing against regular branded packs.

The truth is that there is no evidence that plain packaging would reduce tobacco consumption. The Australian Government, the only government to approve the policy to date, has itself called plain packaging an “experiment”. This study or the results of an opinion poll do nothing to change this fact.

David: Like British American Tobacco, you’ve been quite front-footed on this issue. Why have you chosen this particular one to draw such a pronounced line in the sand?

Christopher: We support evidence-based regulation of all tobacco products. In particular, we support measures that are effective in preventing young people from smoking. Plain packaging fails this standard because it is not based on sound evidence and will not reduce youth smoking. In addition to the above, as a premium brand tobacco company, we oppose plain packaging because it would significantly limit our ability to compete for market share among adult smokers. Instead, plain packaging would turn the legal tobacco industry into a lower-priced commodity business.

David: How’s the debate been going, in your assessment?

Christopher: The international debate over plain packaging is set to continue for some time. Three countries have already lodged complaints in the WTO with Australia over its plain packaging legislation, and a series of international business groups in Australia, the United Kingdom and New Zealand have expressed concern over the impact plain packaging will have on intellectual property rights and trade. To date, Australia is the only country to have enacted plain packaging legislation.

Recent news

Reflections from the 2024 UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs

Executive Director Sarah Helm reflects on this year's global drug conference

What can we learn from Australia’s free naloxone scheme?

As harm reduction advocates in Aotearoa push for better naloxone access, we look for lessons across the ditch.

A new approach to reporting on drug data

We've launched a new tool to help you find the latest drug data and changed how we report throughout the year.