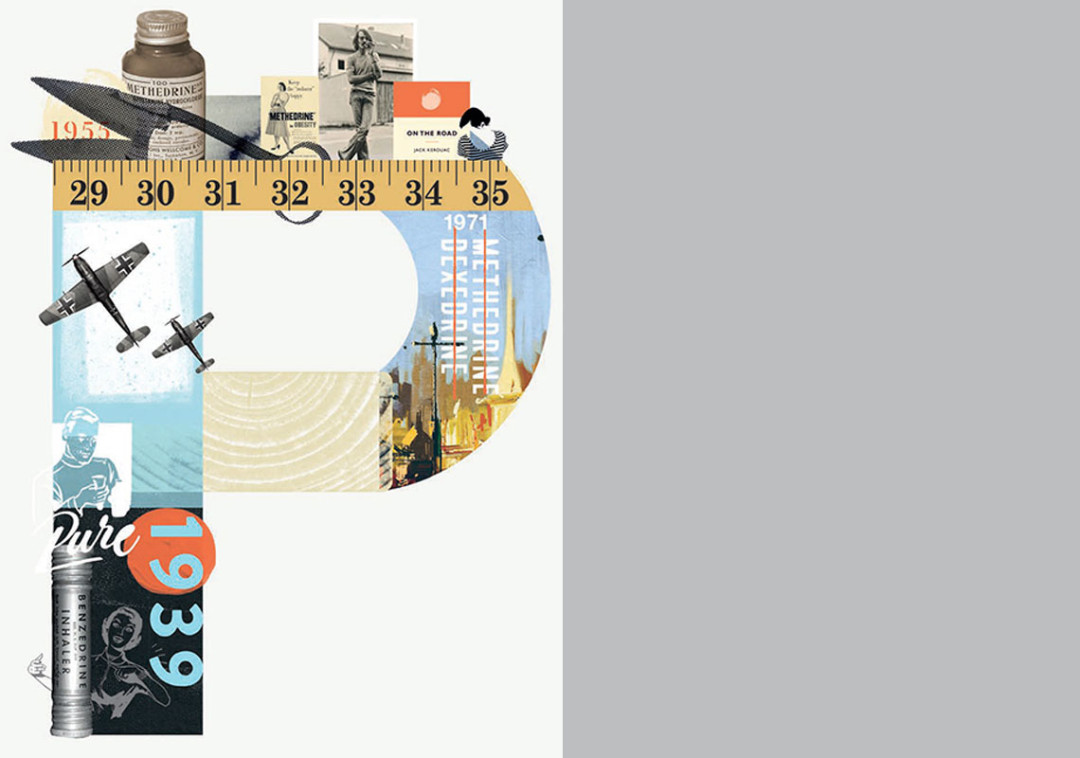

P: New Zealand’s P history

Redmer Yska traces the development of amphetamine manufacture and its history of use in New Zealand.

The current amphetamine epidemic, with its kitchen sink product and chaotic victims, is often painted as an ugly new phenomenon – but New Zealand’s love affair with the drug dates back more than half a century.

Problems with abuse of legal amphetamine first came to light after World War Two when a form of the drug became available over the counter in local chemist shops. By the early 1970s, a full-blown ‘meth’ outbreak saw the flailing authorities ban the drug outright, ordering national stocks destroyed.

How could it happen here? Amphetamine had already been synthesised by 1919, but American drug companies got cracking in the 1930s with the discovery of its decongestant properties. This was the remarkable “brain drug” that enlarged nasal passages and stimulated the central nervous system.

It was first marketed in the USA as the Benzedrine Inhaler, a tube containing a strip soaked in 325 mg of viscous amphetamine base and little else. In 1939, Benzedrine was classified locally as a first schedule poison, available from pharmacies like Burberry and Blinkhorn in Lower Hutt, sold over the counter for about $25.

The stimulant’s ability to promote endurance and weight loss and even, apparently, cure depression deepened its popularity. But it was always lethal. In 1939, New Zealand author Robyn Hyde killed herself in London from a Benzedrine overdose. At the time, the coroner noted the drug “which had the effect of clearing the mind” was “often taken by students who were going to sit examinations”.

World War Two saw amphetamine becoming the drug of choice for combatants on both sides. German troops were issued with a form of the drug known as Pervitin, allowing them to stay awake (and conduct blitzkrieg) for 50 hours in a row. American pilots meanwhile began to swallow ‘pep pills’ newly marketed as ‘methamphetamine’ by global drug manufacturer Burroughs Wellcome.

After the war, the pharmaceutical industry ratcheted up its promotion of amphetamine, at times making bizarre claims. In 1946, the weekly newspaper Truth quoted a drug company boss stating the drug used by the Army during the war to “pep up” fliers on long bombing missions was an “antidote for would-be suicides”, and it was freshly branded as the slimming drug of post-war suburbia.

In 1949, New Zealand drug companies, like their counterparts in Britain and America, began aggressively marketing pure amphetamine as an appetite suppressant. The negative consequences of prolonged use were, however, becoming clear. Reports emerged among long-term users of “sinister voices emanating from toilet bowls” and “spies following one’s every move”.

The local branch of Burroughs Wellcome began promoting Dexedrine, a ‘safe’ slimming aid that reduced a patient’s appetite by half. Headlines like “Dexedrine Can be Dangerous”, however, appeared in local newspapers, as chemists reported local stocks of the tablets were quickly exhausted. In 1950, Health Minister Hugh Watts was sharply questioned in Parliament after chemists raised concerns about the rush of demand for the stimulant.

A Wellington chemist and member of the Pharmacy Board said Dexedrine had been the subject of representations to the Health Department. “Certain types obviously are susceptible to it and an overdose obviously can be harmful. It is not in the public interest that the drug should be sold too freely or taken too freely.”

A relaxed Minister Watt confirmed that a medical prescription was not required to obtain the drug, but if circumstances arose that made it necessary or desirable, the drug would be declared a prescription poison by an amendment to the Poisons Regulations.

Through the 1950s, local amphetamine use continued unchecked and virtually unregulated, as new varieties such as the Burroughs Wellcome global brand Methedrine came on the market. This is the same product now illegally manufactured as ‘P’ or Pure.

In 1955, the ‘pep pills’ issue came to a head with the death of a New Zealand shearer who’d taken Benzedrine to boost his strength for an attempt at the world shearing record. In 1956, the annual conference of hospital matrons at Invercargill urged the Health Department to impose “some sort of control on the sale of slimming pills and that they be made available only on medical prescription”.

Amphetamine, now famously nicknamed ‘speed’, meanwhile became the drug of choice for disaffected post-war youth after use of Benzedrine inhalers appeared in books like Jack Kerouac’s On The Road. Kiwi ‘beats’ seeking black bombers (Dexedrine) and ampoules of liquid methamphetamine began appearing in doctors’ waiting rooms.

In 1960, an amendment to the Poisons Act placed the first formal restrictions on amphetamine, a class of drugs increasing seen as having no place in medicine. A conference of the Australian and New Zealand Association for the Advancement of Science held in Canberra heard of the drugs causing “addiction, madness and murder”.

By the mid 1960s, a moral panic about drug abuse took hold in New Zealand, following a mounting number of prosecutions for imported cannabis and LSD. An epidemic of injecting pharmaceutical Methedrine among young people in America and Great Britain was also mirrored here, but it received mostly scant publicity.

A turning point came in 1969 as a visiting British medical professor described doctors prescribing amphetamine-type drugs for patients who wished to lose weight as guilty of malpractice. Health Department officials, finally conceding there was “recent evidence of misuse of Methedrine”, insisted a crackdown was coming.

However, another year passed before Burroughs Wellcome, which had aggressively marketed amphetamine for decades, finally withdrew both Dexedrine and Methedrine. A senior Christchurch policeman called Methedrine our “most abused prescription poisons drug”.

It took two more years for the Health Department to draw up regulations to ban amphetamines, finally restricting their supply to hospital pharmacies. Destruction of the country’s remaining supplies began in the Auckland warehouses of Burroughs Wellcome. As part of the new controls, local chemists were given three months to clear stocks.

The extent of local prescribing and use may never be known. The Ministry of Health refused to release related archival records for this article, citing privacy considerations. But a clue to the scope of our legal amphetamine story lies on page 178 of the 1973 report of the Drug Dependency and Drug Abuse Committee. The figure for those using prescribed stimulant drugs on any particular day in 1971 was put at “4800 persons”.

Recent news

Reflections from the 2024 UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs

Executive Director Sarah Helm reflects on this year's global drug conference

What can we learn from Australia’s free naloxone scheme?

As harm reduction advocates in Aotearoa push for better naloxone access, we look for lessons across the ditch.

A new approach to reporting on drug data

We've launched a new tool to help you find the latest drug data and changed how we report throughout the year.