There’s something wrong with the sentences

Under the irrelevant and outdated Misuse of Drugs Act, cannabis penalties and convictions in New Zealand remain inconsistent, disproportionate, unjust and largely ineffective, especially for Māori. Catriona MacLennan looks at the facts and at why it’s seriously time to start afresh.

Wiremu* was 15 when the Police first caught him with a tinnie. His age and the small amount of cannabis involved meant he did some community work and the matter was resolved without him getting a conviction.

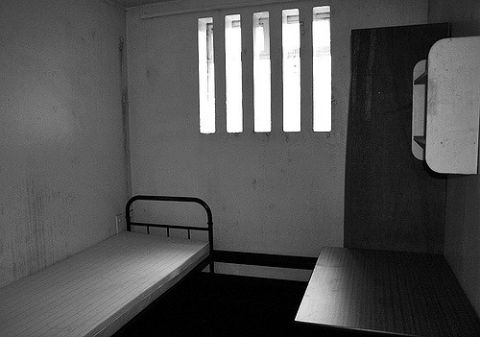

The outcome of his second encounter with drugs charges was vastly different. Wiremu was 18 by that time, and the quantity of cannabis he had in his possession was presumed to be for supply, so he was dealt with in the District Court and sentenced to two years’ jail. That was 16 years ago, and his mother, Anahera,* says the conviction is still blighting his life.

“He did his time, and he came home. I don’t know how many times he’s been turned down for jobs because he’s got drug convictions and people think he’s on drugs. He’s 34 now and he tells me, ‘Mum, it would be better to go back to jail.’ He’s been dragged through the system, and they just won’t let it go. He’s repeatedly gone back to jail because it’s the only place he can get the freedom he’s looking for.” She says only one employer in more than 14 years has been prepared to give her son a chance. Wiremu worked for him for nine months before the boss had a heart attack. The new employer immediately sacked him.

“He gets frustrated with job seeking. He has to go above and beyond to prove he can be a labourer, then he has to go and do drug testing on a regular basis. It’s like he’s caught and doesn’t know how to get out [of his situation]. The worst thing is, he’s not on drugs. He learned his lesson.”

The case that has really galvanised public debate about drug laws and sentences over the past year is that of New Zealander of the Year nominee, community leader and mother of three, Kelly van Gaalen. Police were called to her home to investigate a home invasion and found 650 grams of cannabis in a bucket and 29 grams in a plastic bag.

Van Gaalen was convicted and sentenced to two years’ jail. She served three months in prison before her conviction was quashed by the Court of Appeal and a retrial was ordered. The Court of Appeal said that, if it had been required to consider the appropriateness of the sentence imposed on van Gaalen, it would have quashed the jail term and imposed home detention instead.

When the case returned to the District Court, van Gaalen pleaded guilty to possession for sale, having run out of money and being so distraught by her experience that she wanted finality as speedily as possible. The second time round, she was sentenced to 300 hours of community work and five months’ home detention.

The case ignited a furious public debate on two issues. How could someone making such a big contribution to the community be tossed into jail without being given a chance, and why had van Gaalen received such a harsh penalty when others whose offending appeared more serious had been given lighter sentences?

Comparisons were made with other cannabis cases in which people had avoided jail terms (see sidebar), and the inconsistency in punishments makes it easy to understand the public outcry. All of the examples in the sidebar clearly involved commercial cannabis operations, but in the van Gaalen case, the Police admitted they were unable to find any of the hallmarks of a cannabis operation such as texts and a stash of cash.

Barrister Michael Bott says there is “without doubt” a difference in sentencing outcomes in different parts of New Zealand and that this can be attributed in part to the views of resident judges in different locations.

Bott recently acted for a 21-year-old who was seeking a discharge without conviction for possession of equipment used in the production or cultivation of controlled drugs. The lawyer had a “real battle” to obtain a discharge as that particular judge regards cannabis as a gateway drug.

“A conviction would have affected [the defendant’s] whole life.”

Bott says harsh approaches to drug offending can break up families, and jail sentences ultimately increase the risk of reoffending. He acted for a couple sentenced to jail in 2010. Their children had to be passed around to other family members, and one child dropped out of school, meaning that the parents’ convictions had a lifelong impact on that child.

Whangarei barrister Kelly Ellis says New Zealand’s drug problem has become far worse since this country followed the United States and launched its own war on drugs.

“Dealers are not discouraged by these laws. They are thoroughly encouraged, because they keep prices up. They are what we need to maintain the drug economy. Denunciation doesn’t work. Prohibition has never worked. We need to have a common-sense approach to this.”

She says most people could obtain methamphetamine if they wanted to but do not do so because they are educated about its effects. She says criminalising drugs glamorises them.

“If we treated drugs as a health issue, we would not be branding children as drug criminals. Decriminalisation would just completely depower it. It kills the black market dead. It would be the most incredible thing that could happen to New Zealand. It would reduce burglaries and violence, and Police would have the resources to deal with more serious issues like domestic violence.”

New Zealand’s current cannabis regime impacts particularly – and disproportionately – severely on Māori. Māori are more likely to be arrested and convicted of cannabis offences than non-Māori, with 34 percent of those prosecuted in relation to cannabis being Māori.

University of Auckland Senior Law Lecturer Khylee Quince of Te Roroa/ Ngāpuhi and Ngāti Porou says Māori are more likely to be stopped, searched, arrested and convicted and are less likely to benefit from Police discretion. She describes this as discrimination that breaches civil and human rights laws as well as the Treaty of Waitangi. It also reinforces the social exclusion and marginalisation of Māori into “submerged citizenship”, reducing their ability to participate fully in society.

“The big issue is either it’s an offence on the books that’s prosecuted and applied equally to all citizens or it’s not. Being in the state of quasi-decriminalisation means there is room for discretion.”

Quince, who is a Drug Foundation board member, says it is at the point of discretion that racism and the negatives associated with low socioeconomic status impact.

“I know numerous young Māori and Pasifika people who want to migrate to Australia to work in the mines, but they’re prohibited because of historical drugs convictions. That’s the convergence of race and class issues.”

Quince’s views are echoed by University of Auckland Associate Professor of Sociology Tracey McIntosh of Ngāti Tūhoe, who says differences in policing and enforcement mean the impact of cannabis laws is felt disproportionately by Māori.

“The criminalisation of Class C drugs (which are legally determined to have a moderate risk of harm) criminalises young users and can mean they are more likely when accessing the drug to come in contact with distribution networks including gang-associated networks and criminal networks that can put the young person at greater levels of risk.

“Harm-reduction strategies are compromised by current legislation. I have met young people who have grown up in conditions of scarcity and deprivation where one of the only things in abundance is marijuana because homes are part of drug distribution networks. Legalisation would reduce the black market and the criminal networks associated with the present illicit trade and the considerable profits it generates.”

Dr McIntosh says the younger the age at which people enter the prison system the longer the negative impacts last.

“The inability to secure employment due to a conviction that has resulted in a custodial sentence is likely to lead to cumulative disadvantage and possible long-term state benefit dependence. Moreover, given that cannabis sentences are often significantly less than two years, the individual may not be eligible for any programme while they are incarcerated, meaning that an opportunity for meaningful intervention and engagement is lost.”

Rotorua lawyer Annette Sykes of Ngāti Pikiao says the current criminalisation of cannabis places young people who engage in low-level offending on a conveyor belt towards more serious crime. She points to high imprisonment rates for Māori women and says there is a failure to recognise the correlation between their drug use and poverty, single parenting and other issues.

Our law has as its foundation a presumption that people are innocent until proved guilty. In criminal cases, it is the state’s role to prove that guilt beyond reasonable doubt. But our drug laws turn those basic notions on their head.

The Misuse of Drugs Act provides that, if someone is found in possession of 28 grams or more of cannabis, it is presumed that the cannabis is for supply. The onus then switches to the defendant to try and counter that presumption.

University of Otago Professor of Law Andrew Geddis describes the reverse presumption as an unjustifiable limit on a person’s right to be presumed innocent until proved guilty.

“Requiring someone to show that they are not a criminal just because they have “too much” of a drug is an affront to basic principles of our criminal justice system. At the least, the threshold for any such presumption ought to be much, much higher than at present. But even better would be to follow the UK lead, where if the defence can raise a reasonable doubt about the purpose of possession, then it is for the Crown to prove that the defendant intended to supply others.”

Bott says the rebuttable presumption was introduced to secure more convictions.

“The difficulty is that you have people with chronic pain who use significant amounts of cannabis. As a matter of first principle, everything should be beyond reasonable doubt. I can’t see as a matter of principle that we should have a reverse onus.”

Former Attorney-General Michael Cullen and current Attorney-General Christopher Finlayson have both reported to Parliament that the Misuse of Drugs Act reverse onus is inconsistent and unjustifiable under the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act.

The Supreme Court in the 2007 case of Hansen v R considered the reverse onus in detail, handing down a 123-page judgment. A full court of five judges sat on the case and concluded that it created an unjustified limit on the presumption of innocence. A majority of the judges decided that the reverse onus was not rationally connected to the drug trafficking harm it was designed to cure or was not a proportionate response to the problem.

Chief Justice Sian Elias said making it easier to secure convictions was not a principled basis for imposing a reverse onus of proof.

“It is difficult to see that evidential difficulties for the prosecution in the present case could not have been sufficiently addressed by a presumption of fact, which leaves the onus of proof on the prosecution. It is not at all clear that there is any principled basis upon which the risk of non-persuasion and therefore the risk of wrongful conviction is properly transferred to someone accused of drug dealing.”

…there’s not a single, solitary chance that as long as I’m the Minister of Justice, we’ll be relaxing drug laws in New Zealand.

Ex Minister Simon PowerIt was the reverse onus that caught van Gaalen and led to her receiving such a heavy sentence after her first trial. The amount of cannabis found was more than 28 grams, and it was accordingly presumed that it was not for personal use.

Evidence supporting van Gaalen’s version of events emerged during the Crown case, including admissions by the Police that there was no evidence either of text messages normally associated with cannabis dealing or of instruments such as scales used to weigh cannabis. However, the trial judge made repeated mistakes in explaining the law to the jury. He did not properly explain the reverse onus of proof, and he said van Gaalen could not rely on cross-examination showing a lack of direct evidence of her having sold cannabis.

In 2011, the Law Commission released a report, Controlling and Regulating Drugs – A Review of the Misuse of Drugs Act 1975. It noted the Misuse of Drugs Act was 35 years old and had been developed in the 1970s when the hippie counterculture was at its height and the illegal drugs of choice were cannabis, cocaine, opiates and psychedelics like LSD. The Commission said far more was known now about how drug harms could be reduced, but the Act continued to treat drug use mainly as a matter of criminal policy rather than as a health issue.

The Commission recommended repealing the Misuse of Drugs Act and replacing it with a new law administered by the Ministry of Health. It proposed that it should no longer be an offence to possess utensils for the purpose of using drugs. A mandatory cautioning scheme should be created for personal possession and use offences.

This would involve Police issuing a caution notice when a personal possession and use offence was detected. The drugs would be confiscated, educational material would be provided and details of support services and treatment providers would be given. Caution notices would only be issued when users acknowledged responsibility for their offences. Users would receive a specified number of caution notices, depending on the class of drug.

The paper recommended a statutory presumption against imprisonment in cases of social dealing, provided the offending was not motivated by profit. The presumption should apply to all dealing offences and all drug classes but should not apply when the dealing was to persons under 18.

In relation to the reverse onus of proof, the Commission suggested the offence of possession for supply should be replaced with an aggravated possession offence. This should be defined by reference to the quantity of drugs possessed, which should be set on a drug-by-drug basis. An expert advisory committee should advise the government on the quantities of drugs that would comprise aggravated and simple possession.

The National Drug Policy 2015 to 2020 sets out the government’s approach to alcohol and other drug issues, with the goal of minimising harm and promoting and protecting health and wellbeing. It is supposed to be the guiding document for policies and practices responding to drug issues, with the government using it to prioritise resources and assess the effectiveness of actions taken by agencies and frontline services. However, its health and harm-minimisation approaches run directly counter to the Misuse of Drugs Act’s focus on crime and punishment.

The policy requires the government in 2017/18 to “develop options for further minimising harm in relation to the offence and penalty regime for personal possession within the Misuse of Drugs Act 1975”.

The Law Commission’s report was published five and a half years ago, but its core recommendations have not been implemented. The government has acted on the suggestions relating to psychoactive substances, and the Ministry of Health is currently reviewing the law relating to drug utensils. A July 2016 discussion document suggests there could in future either be an “enhanced status quo”, which would continue the prohibition on utensils but reduce criminal penalties, or the ban could be replaced by regulations aimed at informing and reducing harm.

However, New Zealand’s three-yearly electoral cycle and the desire by politicians to outbid each other to appear tough on law and order weigh heavily against major moves to adopt a more constructive approach to cannabis.

Then Justice Minister Simon Power could not move speedily enough to pour cold water on the Law Commission’s suggestions and rule out any relaxation of drug laws, saying “there’s not a single, solitary chance that as long as I’m the Minister of Justice, we’ll be relaxing drug laws in New Zealand”.

Current Justice Minister Amy Adams declined to provide any response at all to a detailed list of questions submitted to her for this story.

JustSpeak spokesperson Julia Whaipooti of Ngāti Porou supports the Law Commission’s recommendations and says cannabis should be treated as a health issue rather than a criminal justice matter. She says the current regime has long-term impacts on people’s lives and is ineffective at preventing harm.

In particular, the stigma of cannabis convictions impacts on young people’s ability to obtain jobs for the rest of their lives.

“It actually does nothing to deter harm and create safety for the community. The purposes of going through the criminal justice system are not served by convicting people for minor drug use.”

JustSpeak points out that, between 1994 and 2011, the rate of prosecution for young people caught with drugs almost doubled. In 1994, the figure was 5.5 percent, while in 2011, it was 10.5 percent. Of the 1,019 drug possession or use offences in 2011 for 10 to 16-year-olds, 989 (97 percent) related to cannabis. JustSpeak says the data points towards the exercise of Police discretion changing.

Those outcomes for young people run counter to the general trend of reduced arrests and convictions for minor drug offending. Between 2011 and 2015, the number of people convicted of possession or use of illicit drugs or drug utensils fell from 4,997 to 3,140.

The figures for young people are particularly disturbing because the impact of drug convictions stays with them for the rest of their lives. The Clean Slate law applies only if people have not had convictions in the past seven years, have not been sentenced to jail and are within New Zealand, so young people planning to travel to Australia for a fresh start still have to declare their drug convictions.

Quince is calling for a full review of the Misuse of Drugs Act.

“Martin Crowe was not prosecuted [for using cannabis]. The elephant in the room is that certain people are never going to be stopped, prosecuted, convicted or punished. The harm to Māori communities is huge. I don’t know whether we want to decriminalise. We want to review, but there has to be a holistic approach. The hundreds of millions of dollars spent on trying to control cannabis needs to be spent on education and harm reduction.”

Sykes says cannabis-related offending should be treated as a health issue, and there should be a change of focus away from criminal justice and towards providing psychological and psychiatric services, whānau support and education.

Criminalising drug taking to stop the problem of addiction is like making sex illegal for under 20-year-olds in order to prevent teenagers getting STDs.

Andrew GeddisGeddis emphatically states that the Misuse of Drugs Act is no longer fit for purpose and the whole focus of drug law is misconceived.

“The use (and abuse) of drugs is first and foremost a public health issue with which the criminal law ought to have very little to do. Criminalising drug taking to stop the problem of addiction is like making sex illegal for under 20-year-olds in order to prevent teenagers getting STDs.”

Geddis says the social harm done by stigmatising drug users as “criminals” and burdening them with convictions that radically limit their future options is far greater than any benefit gained from reducing harmful drug taking.

“We also need to be aware that lots and lots of New Zealanders (myself included) have possessed and used drugs without suffering any harm from doing so. The state has no more justification labelling such people “criminals” than it does criminalising mountain climbing on the basis that this is a risky pastime that kills some of those who engage in it. If there are dangers associated with taking drugs, then minimise those dangers (by letting people know what they are taking) and concentrate on providing help and care for those who become addicted to them.”

Bott supports implementation of the Law Commission’s recommendations and is another who believes cannabis should be regarded as a health issue.

“The trouble is there is not the political will at the moment to do that. You are seen as soft on law and order. It’s a question of the approach: not being soft on crime but doing something that works rather than criminalising young people for the rest of their lives at an early age … I’ve had cases again and again where people lose jobs because of drug convictions even if they are just for cannabis. If we decriminalise, that takes the stigma away and you can look at what actually works. I see so many young people who use cannabis socially and get convictions and then become almost unemployable.”

Community Law Centres see many people suffering discrimination years or decades after receiving drug convictions. Te Tai Tokerau Community Law Centre manager Dr Carol Peters says people with drug convictions face major difficulties in obtaining jobs. She would like to see alternatives to criminalisation more widely available, particularly Iwi or Community Justice Panels, which address the causes of behaviour and provide an element of restorative justice.

A Community Justice Panel was set up in Christchurch in 2010, and three Iwi Justice Panels have subsequently been established in other locations. The panels are a joint initiative between Police and local communities, which aims to hold people to account and produce positive outcomes. Community Law Canterbury Manager Paul O’Neill has been heavily involved with the Christchurch panel and says the results have been impressive, particularly in terms of reducing recidivism. More than 600 cases have been dealt with in Christchurch, with three community representatives sitting on each panel. The panels can be tailored to provide the expertise required in each case, for example, mental health or drug knowledge.

A shift away from locking people up is something Gilbert Taurua says will overturn what can be the lifelong impacts of drug convictions. Taurua, who started at the Drug Foundation earlier in 2016 as Senior Adviser, Māori Liaison and Advocacy, looks at the high rates of Māori incarceration for minor drug offences and queries what they mean for people’s future employment prospects. He says jail sentences for Māori do not appear to reduce the prevalence of drugs.

Taurua, of Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Kawa/Te Atihaunui Pāpārangi and Ngāti Pāmoana, is leading an advocacy campaign called “Tautāwhihia. Kaua e whiu” (Support. Don’t Punish).

Instead of using the strong arm of the law, Taurua says we need to look at international developments for models.

“I think we need to learn about what is happening overseas to inform what we need to do in New Zealand. It’s like the momentum is growing, and we know change needs to happen, but what that change looks like, particularly from a Māori community perspective, is going to be part of our challenge.”

He points to Portugal where people caught with a small quantity of an illegal drug for personal use are referred to a local Commission for Dissuasion of Drug Addiction. The commissions consist of a lawyer, a doctor and a social worker. Sanctions can be applied, but the main aim is to explore the need for treatment and to promote healthy recovery.

Whatever route things take, change can’t come soon enough for those who have witnessed the debilitating aftermath of a conviction. Wiremu’s mother, Anahera, who has seen the impact of a drug conviction last more than a decade after the sentence was completed, says radical change is needed.

“They’re living in a dream world if they think their laws are working at ground level. Anyone at the Beehive should come up here and see what’s happening. They need to do something because we’ve got strong, healthy men rotting in our jails. Where’s the justice in it?”

* Names have been changed to protect identifies.

Photo credit: flickr.com/stillburning

Recent news

Reflections from the 2024 UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs

Executive Director Sarah Helm reflects on this year's global drug conference

What can we learn from Australia’s free naloxone scheme?

As harm reduction advocates in Aotearoa push for better naloxone access, we look for lessons across the ditch.

A new approach to reporting on drug data

We've launched a new tool to help you find the latest drug data and changed how we report throughout the year.