Cheese, chocolate, watches - and heroin-assisted treatment

By the 1990s, Switzerland had the highest injecting drug and HIV infection rates in Europe. Its first attempt to contain the problem was to declare Platzpitz Park in Zurich as somewhere heroin users could inject free from arrest. Up to 3,000 users visited ‘Needle Park’ daily, and it quickly became a cesspit of misery, crime, filth and death.

Staggered by the size and visibility of the problem and seemingly out of options, Swiss authorities sat down with community and civil society workers to find a solution that sought to manage drug problems rather than declare war on them.

The four pillars

Switzerland’s national drug policy, introduced in the 1990s, comprises four pillars: prevention, therapy, harm reduction and prohibition. Though experimental and radical, results spoke for themselves, and the Swiss public voted the approach into law in 2008.

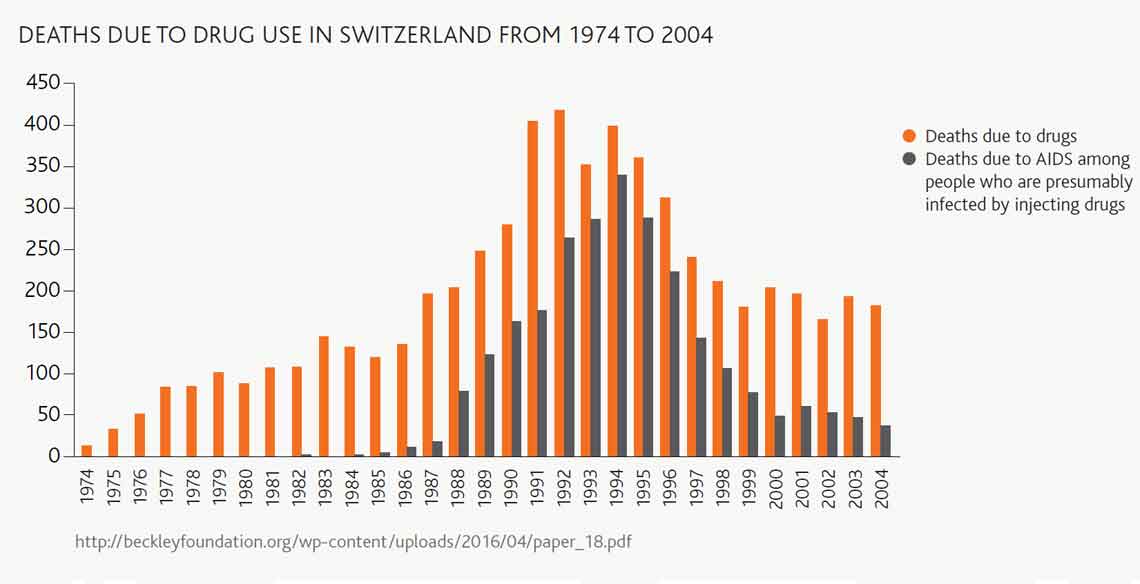

The number of drug users in treatment rose dramatically. By 2004, drug-related deaths had reduced by 50 percent and deaths related to HIV and hepatitis by 90 percent.

Effective approaches under the four pillars included needle exchange programmes, medically supervised injecting rooms and free substance-checking at festivals. Possession of up to 10 grams of heroin was decriminalised in 2013.

The model’s seemingly contradictory components are one of its strengths, allowing for different approaches under a shared vision. Prohibition conforms to international drug treaties, while other pillars allow for emerging harm-reduction initiatives.

Bar graph showing deaths due to drug use in Switzerland - Deaths due to drug use in Switzerland from 1974 to 2004.

Heroin-assisted treatment (HAT)

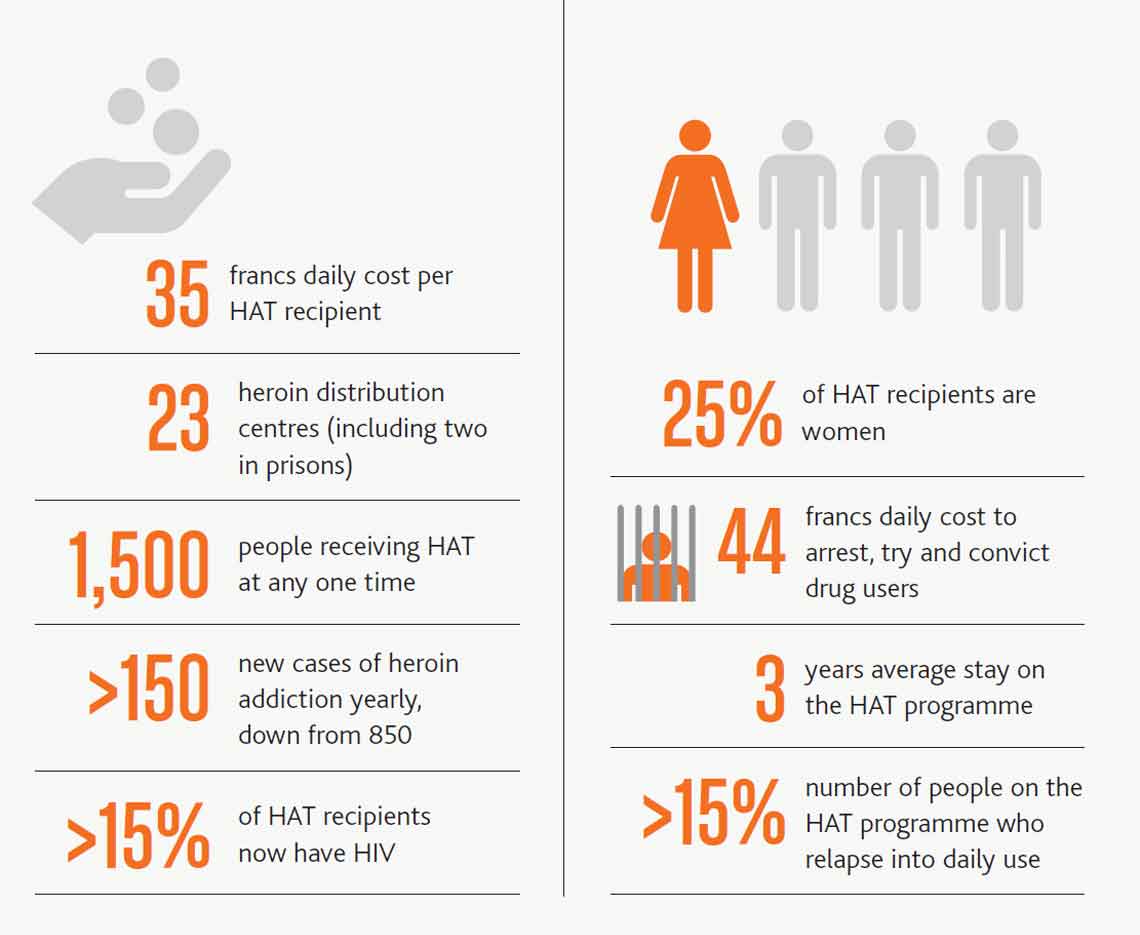

Switzerland introduced HAT in 1995, and now more than 70 percent of Swiss people addicted to opiates are in substitution therapy. Those for whom methadone and other therapies don’t work receive prescribed heroin.

Within a year, it was noted that HAT participants carried out 55 percent fewer vehicle thefts and 80 percent fewer muggings and burglaries. The numbers of drug dependent people dying fell dramatically, and a third of those receiving welfare found jobs.

Why does HAT work?

Rather than patients asking for increasing amounts of free heroin as may be expected, once they have gained some stability and returned to reality, they seek to start reducing their daily doses. People rediscover themselves and other meaningful aspects of life. The average patient spends three years on the programme, and by the end of that time, only 15 percent are still taking heroin daily.

It disrupts the drug-selling pyramid. People with heroin dependency no longer cut what they’ve bought with harmful powders and on-sell it to finance their own drug use. This also helps reduce initiations to heroin use.

The clandestine rituals and ‘us versus them’ culture around heroin use, attractive to some, has disappeared, further reducing new initiations.

Is this relevant to New Zealand?

While the particulars of the HAT programme may not apply to New Zealand, the principles of public health programmes like this are relevant. The seemingly radical idea of making heroin supply more accessible in prescribed circumstances, combined with health and social interventions, has led to big health gains in Switzerland. This includes reduction in overall use. The same principles behind HAT can be used to find solutions to problematic methamphetamine use here.

Graphic image showing statistics around Heroin-assisted treatment

Recent news

Reflections from the 2024 UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs

Executive Director Sarah Helm reflects on this year's global drug conference

What can we learn from Australia’s free naloxone scheme?

As harm reduction advocates in Aotearoa push for better naloxone access, we look for lessons across the ditch.

A new approach to reporting on drug data

We've launched a new tool to help you find the latest drug data and changed how we report throughout the year.