Where there is life, there is hope

Harm reduction is about saving lives and treating people with respect. While we led the world with the first government sanctioned needle exchange 20 years ago, what is the current state of harm reduction services, and how can they be scaled up for greater impact?

The exchange

It’s brisk business at Wellington’s needle exchange. About every five minutes this Monday afternoon, the bell rings as someone enters from rain-soaked upper Willis Street into a brightly lit, functional interior. The walls of a small waiting area are lined with health pamphlets about preventing HIV, preventing hepatitis C and safe sex.

Two large square holes are set into the bare counter with bright yellow bins beneath – one for loose used syringes and needles and one for the same equipment housed in specially created plastic containers.

Debby, friendly and matter of fact, chats with the people who come in about the awful weather as they drop used equipment into the bins. She then issues them with fresh kits, encased in an anonymous plastic bag. They’re in and out in seconds.

In 1987, New Zealand became what is thought to be the first country in the world to introduce a national needle exchange programme (NEP) in response to the HIV/AIDS pandemic. Dr Michael Baker, now Professor of Public Health at the University of Otago, was a medical advisor in then Minister of Health Michael Bassett’s office. He became an advocate and chief architect for the NEP.

There was uncertainty about how to respond to the emerging HIV/AIDS epidemic, which was starting to cause explosive outbreaks in injecting drug user populations in the UK and USA,” Dr Baker said. “The traditional response was to be tough on drugs, but there was a pervading air of reform about the Lange government, and they were willing to consider a different approach.

“Even at that time, there were individual pharmacists who sold needles and syringes so users could inject more safely, so there were precedents for the programme.

“It was not plain sailing. The government’s AIDS Advisory Committee was very wary. They were worried about unintended consequences such as an increase in the supply of needles and syringes fuelling the HIV epidemic. There was also concern because a national NEP had not been tried elsewhere. But everyone was well briefed on what we wanted to do, including opposition MPs.

“In the end, the legislation went through smoothly. I think there was by then a fairly pragmatic approach in New Zealand towards preventing HIV/AIDS.”

There are now 21 needle exchange outlets, which have adopted a peer service model, meaning former injecting drug users are encouraged to join the staff. There are about 180 pharmacies involved and dozens of sexual health centres, Prostitutes Collective offices and base hospital and community clinics. In 2004, the scheme was enhanced by the 1-4-1 programme providing new 3ml barrels with any needle free to customers who brought in used syringes and needles. Today, the programme provides in excess of two million sterile needles and syringes each year to people who inject drugs (PWID).

The success of the programme is highlighted by the fact that among people who inject drugs and who use needle exchanges, the HIV rate is just 0.3 percent. (In the American capital, Washington DC, where there is no formal needle exchange programme, the rate is 50 percent.) A 2002 international review indicated that, for every dollar spent on the programme, it saved taxpayers more than $20 in downstream health costs.

At Wellington’s needle exchange – officially The Drugs, Health and Development Project (DHDP) – Debby explains why the NEP is so successful. “Our job is to issue equipment that will keep clients safe while they inject. It’s not to get them to detox, go on methadone or anything else.

“I don’t ask questions, judge or advise,” she says.

Sometimes clients ask for contacts of a doctor, dentist or counsellor. Once a month, a nurse specialising in hepatitis C – the scourge of the drug injecting community – visits. In Wellington, a GP used to hold a Wednesday afternoon clinic, but funding ran out.

Rachel, another staff member, tells me the DHDP would make a great hub for health and social services.

“We have a rapport with our clients. They trust us, and through us, they could engage with the support they need.”

Rachel runs through a wish-list: Work and Income, budget advisors, housing, an onsite nurse and/or doctor, career advisors.

“The money spent would be more than justified when you think what will need to be spent down the track, especially on health.”

But such services look likely to only remain on a list of wishes for now.

DHDP General Manager Carl Greenwood says one of the biggest problems he encounters is the shame pervading the drug-using community. “The stigma of being a person who injects drugs means they try to be invisible, and that prevents us getting health information to them, which stops them engaging with services they really need.”

Rachel says a national awareness campaign highlighting drug injection as a health issue, while de-emphasising it as a criminal activity, would help reduce that stigma. The Ministry of Health’s Director of Mental Health John Crawshaw says the idea has possibilities. “We are willing to discuss the evidence for this issue and actions to address it,” he says.

While the programme has been spectacularly successful in keeping HIV out of the PWID community, hep C, as the programme’s General Manager Charles Henderson explains, is an entirely different story.

“Hep C was already established in the injecting community by 1987. It’s much harder to eradicate a virus from a population than it is to prevent it becoming established in the first place. Seroprevalence studies of HIV, hep B and hep C in needle exchange attendees in 2009 indicated one in two had been exposed to hep C, but that was down from 70 percent in 2004.”

Carl Greenwood hopes Wellington’s DHDP will become a focal point for the prevention of liver-destroying hepatitis C. “So we’re not just a centre for education, but also for rapid testing – with results in minutes not days – counselling and on-referrals. We have our clients’ trust; it makes sense to use that.”

But the Ministry of Health, which funds the needle exchange programme at $4.3 million a year, will only say non-committedly that it is “keen to continue to work with providers about how the programme can be improved”.

Charles Henderson says the programme could achieve much more.

“Whether New Zealand needs facilities like Vancouver’s Insite (see sidebar below) is a moot point,” he says. “We do not have as much street use of drugs, and the types of drugs involved are different.

“But we do need similar services: nurse-led health clinics, better links to mental health services, nutrition and housing. We could have vaccination programmes and an outreach co-ordinator in every centre to support hard-to-reach people who inject drugs: those in rural areas, youth, new initiates, same sex-oriented individuals, steroid users and Māori.”

Charles Henderson sees the growing toll of doing nothing about this.

“Liver clinic extrapolations show 50,000 New Zealanders have been exposed to the hep C virus – the large majority via injecting drug use. Research indicates that people who inject drugs are very ‘health services intensive’. We cannot afford to do nothing and hope the problem will go away.”

Opioid treatment

A Wellingtonian who decides they have had enough of life dependent on illicit opioid drugs can make their way to the Opioid Treatment Service (OTS) on the northern fringe of the city’s CBD. Here, they can put their lives into the hands of the specialist team there, one of 18 around the country. It’s where I met Peter, who’s been on the opioid substitute methadone for four years.

“When I got here, I reckon I had about six months left in me,” the 56-year-old father of three grown sons says.

Peter injected opioids from the age of 17, with a 15-year gap when he was raising his family. He is here to prepare for a move to general practice care in the community. He’s been coming to the service each month for 48 months to pick up a methadone prescription and going four days in seven to a local pharmacist to get his dose.

A new client to the OTS undergoes rigorous assessments for physical and mental health. Then their first real test begins – the wait for treatment.

“The waiting is terrible,” says Peter. “You make this really big decision you don’t want to do this anymore and you want to be well. So you come here, you have to have all these tests, and your head is getting ready to make the big change, but then you have to wait. So you keep using.”

Team leader at Wellington’s service Clarissa Broderick says there are about 20 people currently waiting about six months for treatment. “While that’s down from about 100 people waiting up to two years back about 2005, we do still lose them, they move, they go to jail.”

One of the other major reasons for waiting lists is the lack of general practitioners willing to prescribe opioid substitutes, usually methadone, to patients out in the community.

These patients have already been with a specialist opioid treatment service for a while, have stabilised on the right dose for them, got other aspects of their lives back on track and are now ready to transfer to GP care.

“That normalises their condition as chronic and treatable, no different from type 2 diabetes,” says Clarissa Broderick. “Also, a GP can treat their health as a whole.”

But at many services, stabilised clients are log jammed at the exit. This can happen in areas like the Kapiti Coast, where there aren’t enough GPs, but also because many doctors are reluctant to take on methadone patients.

Alistair Dunn, a GP and addiction medicine specialist in Northland, surveyed

fellow doctors about joining up to the OTS. Of those not already prescribing an opioid substitute, 75 percent didn’t want to. They were worried about their lack of knowledge and experience, about work overload, time constraints, pressure from patients to increase doses, about the effect of their presence in the waiting room and the perceived complex and challenging nature of the patients

But Dr Dunn’s colleague Andrew Miller, who has prescribed methadone for about 15 years, says he’s never experienced stress or risk with his patients.

“They are motivated for me to prescribe because they don’t want contact with ex-associates still under specialist care, and they’re keen to have methadone seen as a normal medication. I’ve formed very satisfying relationships with my patients, and I’ve seen many come right off methadone,” Miller says.

Blair Bishop, liaison between Wellington’s Opioid Treatment Service and local GPs, says the region could do with double its current 60 prescribing doctors. He says many find the paperwork around controlled drugs tedious and time consuming.

“There is no monetary compensation. If Care Plus, for instance, was available to a patient, then that would largely cover the face-to-face costs of the GP practice and help cover the cost of the visit for the patient. But ironically, since Care Plus is available only to patients with at least two conditions, our healthiest clients do not qualify. They are sometimes the most reluctant to move to GP care because of the cost of seeing the doctor and the monthly prescription.”

Andrew Miller says cost for his patients has been removed by subsidies from Northland District Health Board.

One way of managing the waiting lists is interim prescribing of methadone, enabling a specialist service to prescribe a small dose of methadone for people who have not yet begun formal opioid substitution treatment. But many services have not taken it up, regarding it as “sub-optimal” treatment and its use likely to hide the problem of excess demand.

National Addiction Centre research in 2008 found an estimated 10,000 people in New Zealand had a daily opioid dependence and about 4,600 were receiving treatment. It looked at why more did not seek help.

One of the other major bones of contention for client-patients is that of ‘takeaways’: doses of opioid replacement given to clients by pharmacists to tide them over a few days. Normally, clients swallow the dose in front of a regular pharmacist, and that means possibly daily trips to the pharmacist – before work, if people are holding down jobs. Clients complain it ties them to a certain pharmacist and a certain area. They want more flexibility with takeaway doses but, as Raine Berry of the National Association of Opioid Treatment Providers (NAOTP) explains, it is not a simple issue.

“Opioid Treatment Services have to balance the needs for client autonomy and the mitigation of potential harms caused by the inappropriate use of takeaway doses. There is a market for ‘diverted’ methadone, so prescribers have to be constantly aware of the safety of the community. But the lack of flexibility can be frustrating for clients who want to engage in spontaneous or unplanned activities such as going to the beach for the day or spending the night somewhere other than at home. There is no easy way to manage this, unfortunately.”

A second barrier to a number of would-be OTS clients is the attitude towards them of staff. Although national guidelines for opioid treatment providers state that staff with “higher punitive and abstinence orientation (are) associated with lower retention of clients in programmes”, the country’s 18 services do vary in their approach to the people they are treating.

NAC researcher Dr Daryle Deering says that’s because they depend very much on the philosophy of the clinical leaders at each centre.

“Some are more paternalistic and take an approach counter to the literature on effective treatment,” she says. “For example, they insist other drug use – other than nicotine or perhaps cannabis – has to stop before a client starts receiving opioid substitution treatment, and that is reinforced later by regular urine tests. If other drugs consistently show up in those tests, rather than taking a clinical individualised approach, a contractual protocolised approach is taken, leading to a loss of privileges should the client not meet service ‘rules’.

The danger of such an approach is that those people with the most complex issues are excluded from treatment. In some cases, those services who do not demand strict compliance with rules will be able to take people faster than those whose criteria for entry includes stopping other drugs.”

A third major barrier is the stigma associated with being a person who injects drugs – perhaps reflected by the fact that GPs are allowed to refuse to treat a patient requiring an opioid substitute, but no other.

“Even we feel the disapproval of other health workers,” says Clarissa Broderick. “And the stereotypes of an opioid treatment client makes my blood boil.

Methadone helps them get their children back from care, hold down jobs, find homes. They have vastly improved physical health and re-engage with life and their community. The programme reduces criminal activity and the risk of transmitting blood-borne viruses to other New Zealanders. What is so awful about all that?”

Dr Daryle Deering says what is needed are positive recovery stories, aimed at people who inject drugs and the wider community, highlighting that opioid treatment is effective.

And it certainly is. A 2004 study investigated the costs and benefits of methadone treatment amongst a Christchurch client sample and found treatment saved $25,000 per life year.

Those on the frontline of providing opioid treatment would like some more of those savings returned to them. In addition to treating opioid dependence, they are expected to support and improve their clients’ psychosocial wellbeing and that of their families. They say they could do that a lot better if they had adjunct services to provide a more holistic approach: employment advisors with concrete options for job training, housing advisors, parenting skills workshops, budgeting advice and counselling.

Wellington methadone client Peter believes housing is a top priority. “To get away from people hassling you for your methadone, somewhere that’s yours and secure and warm, that’s essential to recovery. I’ve seen people here transform from really jittery to really calm in weeks, just because they’ve got stable and safe accommodation.”

But such services cost money, and Clarissa Broderick, for one, says her team is just trying to work smarter with the resources they have because they know no more money is coming.

That is despite the World Health Organization declaring in 2004 that “every dollar invested in opioid dependence treatment programmes yields a return of between $4 and $7 in reduced drug-related crime, criminal justice costs and theft alone. When savings related to healthcare are included, total savings can exceed costs by a ratio of 12:1.”

NAOTP Chair Eileen Varley says the welfare sector can also benefit through reduced family stressors and may help divert children from CYFS involvement in their lives, as well as individuals having the potential to move from benefits to employment.

“These savings have both financial and social benefits, and it leads to the question of whether the justice and social welfare sectors could contribute to a service that has such direct benefit for them.”

Charles Henderson questions why the government continues to pursue illicit drug use as a largely criminal justice issue when research and overseas experience points to fewer taxpayer dollars being spent if it is treated largely as a health issue.

“It would be a pragmatic response to illicit drug use and its related harms, just as setting up the world’s first national needle exchange programme was a pragmatic response to the HIV/AIDS epidemic.”

Clarissa Broderick agrees, saying the irony of imprisoning someone who is waiting to access opioid substitution treatment is that methadone is inexpensive. “Packing someone who injects drugs off to jail makes no economic sense.”

So maybe the easiest method of reducing stigma and shortening those queues to access help lies with the GPs. Whangarei GP Geoff Cunningham, who has prescribed methadone for 15 years, says he would encourage his fellow doctors to climb on board.

“Our patients have been selected very carefully to transfer from specialist to GP care. They are stable and well managed, and I’ve had nothing but good experiences with them. They are colourful, delightful characters, and it is easy to build rapport with them. In some ways, it is the most rewarding aspect of my practice. These guys are successfully rebuilding their lives and health, and you get to be a big part of it. Who wouldn’t enjoy an opportunity like that?”

Penny Mackay is a Wellington-based radio and print journalist.

----

An insight into Insite

Possibly the finest example of harm reduction in the world, Insite in Vancouver, opened its doors in 2003 to intravenous drug users as a place where they could inject safely and connect to services like addiction counselling and treatment and to social services such as housing.

Insite was the result of at least 10 years of unceasing agitation by its prime movers, who never missed a chance to talk publicly about the absolute need to prevent overdose deaths and the spread of blood-borne viruses and HIV/AIDS. They handed out pamphlets to motorists, appeared in the media, presented at conferences and worked with anyone they thought could help: journalists, educators, researchers, drug users’ families.

They were energised by the soaring rate of overdose deaths in Vancouver’s East Side community, which, in 1997, reached 400. HIV was also endemic, with about one in four having the virus.

“It was such a sad and painful time for us,” says Liz Evans, a nurse and one of Insite’s creators. “We lived in the community, and we knew and were really fond of the people who were dying. Then one day, and I remember this really well, Bud (poet, singer and champion of the homeless Bud Osborn) came back from yet another funeral, and he was so angry and he said to me and Mark (Liz Evans’s colleague and partner Mark Townsend) and our colleague Kirsten, “We’ve got to do something about this”.

“And we said, ‘Okay, we gotta do something’ We didn’t really know what – just something”. In 1993, Liz Evans had founded the non-profit Portland Hotel Society to run one of Vancouver’s ‘single room occupancy’ hotels: budget accommodation for otherwise homeless people.

“We realised many also had serious illnesses and complex social problems, and we found, in that first year, about 88 percent of people we were housing were injecting drugs.”

Support services were also desperately needed for the 6,000 drug injectors in the East Side. “There really wasn’t anyone around who was watching what was going on.”

So the fight for something better began. “There certainly wasn’t much appetite back then for a big change from traditional drug treatment and enforcement. But after about a decade, the health authorities were on board, there was enough political leadership to make the funding thing happen, the Police were onside, and it was kind of miraculous really.”

Today, Insite operates through an exemption from Canada’s Controlled Drugs and Substances Act. Clients inject pre-obtained illicit drugs under the supervision of healthcare staff who supply clean equipment and know what to do if an overdose occurs. (There hasn’t been a single death at Insite, despite more than 1,400 overdoses.) Wounds and infections are treated, immunisations given.

One floor above Insite is Onsite, where clients wanting to withdraw from drug use can be accommodated and looked after. Once clean, they get all-around support to plan their post-addiction lives.

Surveys indicate public support for Insite is about 70 percent, and the facility’s funder, Vancouver Coastal Health, says it does “outstanding” work, has made a positive impact on thousands of clients, saved lives and provided vital health services to a vulnerable population.

Insite has been the subject of about 50 reports and peer-reviewed papers in prestigious scientific journals. They indicate that people who inject drugs who visit the facility are more likely to enter treatment and counselling, that it reduces the spread of HIV and hep C, reduces injection-related infections and improves public order. Its annual budget of $3m is also worthwhile economically. For every $1 it spends, Insite’s benefits are calculated to be worth up to $4.02.*

Despite the positive findings and widespread public support, in 2006, the federal government eliminated harm reduction as a pillar of Canada’s anti-drug policy (the other three being prevention, treatment and enforcement) and began to threaten Insite with suspension of its precious drug law exemption. The battle went all the way to the Supreme Court, which, in 2011, ruled unanimously in favour of Insite’s continued operation.

But in June, the federal government introduced tough new regulations over Insite’s annual application for its exemption, the Health Minister saying, “sanctioned use of drugs obtained from illicit sources has potential for great harm in the community”. Insite’s lawyers are now looking at the implications.

Liz Evans says much of the opposition to Insite is based on ideology, fear and ignorance. “It flies in the face of voluminous evidence that it saves lives and limits the spread of disease. It’s frustrating because, when something has been so robustly researched, it seems like these things should not be in question any more. I don’t want people to use harmful drugs either, but they are a reality. Research shows Insite does not motivate drug taking, but it does save lives, misery and money.”

---

The Wait

Opioid Treatment Services (OTS) are regionally operated around New Zealand. In some areas, people are waiting up to six months to get onto a service. For people in other cities, it is a matter of days.

Wellington

20 people — waiting list for up to six months

OTS Team Leader Clarissa Broderick: We have been two full-time case managers down for about six months. It is hard to recruit the right people and then hold on to them when they face heavy workloads of sometimes complex and challenging cases. Premature burnout is not rare. We expect applicants to have specialist qualifications and a particular skill set. I’m uncompromising on that because we value the standard of care we provide.

Auckland

0 people — no waiting list

Tries to take clients from first presentation to first dose within days. Auckland OTS Manager Toni Bowley: We are a large service with a large staff and can operate economies of scale. This means we can have admissions based on clinical capacity rather than being restricted to a funded number of opioid substitution therapy places. The criteria for entry to our service are also lower than for some other services. This does not come without its problems, as staff caseloads swell and can become a challenge to manage.

Christchurch

0 people — no waiting list

Clinical Director Speciality and Addiction Services, Canterbury DHB Specialist Mental Health Services Dr Alfred Dell’Ario: We haven’t had much difficulty recruiting or retaining staff so don’t have any specific difficulties around waiting times. The service is closely aligned with primary care, allowing the majority of clients to be treated in the community. We have 164 GPs willing to prescribe, and 77 of them are engaged with clients currently.

Whanganui

2 people — waiting list for up to six months

Mental Health Clinical Director Frank Rawlinson: We have a capped number of places that are based on general population. This means no one can enter the programme until someone else is stabilised enough to move on. We could do with more GPs out in the community willing to prescribe opioid substitute.

West Coast

2 people — waiting list for up to two months

Programme Co-ordinator Paul Eathorne: We have a problem recruiting people to the West Coast and keeping them here, especially prescribing GPs. We are funded for 51 people but currently have 75 on the books, and just five are out on GP authority.

Dunedin

0 people — no waiting list but that is about to change

Medical Director CADS Dr Gavin Cape: We are simply not funded for everyone who needs our service. Two or three years ago, we had a waiting list and addressed that using interim methadone prescribing.

Gisborne

0 people — no waiting list

Medical Officer for Opioid Treatment Programme Dr Patrick McHugh: Our managers have smaller caseloads than the larger busier centres so they can perhaps spend more time with each client addressing their psychosocial needs. That means we can move them through the service quite quickly. We don’t seem to have a problem recruiting staff, and I know all the local GPs so don’t really have a problem recruiting them either.

Nelson-Marlborough

0 people — no waiting list

Addiction Services Manager Eileen Varley: NMDHB Addiction Service has developed a twice-weekly drop-in clinic for stable clients to be seen by clinicians. It enables clinicians to focus their time on other clients with higher needs or circumstances requiring greater time input. The clinic means a more effective use of clinician time, which helps ensure waiting lists can be managed proactively.

Rural Otago

0 people — no waiting list

This service is at capacity but with no waiting list at present. There are more people being transferred in, especially from Christchurch. Medical Director CADS Dr Gavin Cape: The OTS service in Otago has underestimated the number of people in Otago with serious drug problems and CADS has an OTS case load far greater than it is funded for, which has stretched our service provision to the limit. I believe CADS is attempting to respond to the community need but lacks full resource support to continue to do so.

Recent news

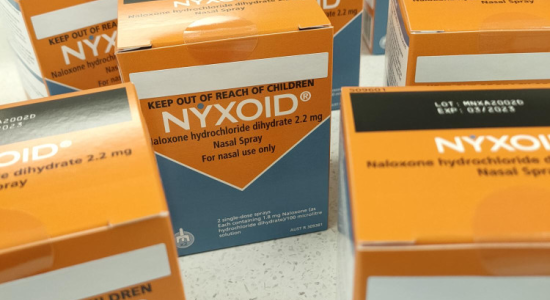

Expert Pharmac committee recommends funding for overdose reversal nasal spray

Public funding for a lifesaving opioid overdose reversal nasal spray is one step closer, with an expert committee saying that funding the medicine for use by non-paramedic first responders and people at high risk of an opioid overdose is a

Reflections from the 2024 UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs

Executive Director Sarah Helm reflects on this year's global drug conference

What can we learn from Australia’s free naloxone scheme?

As harm reduction advocates in Aotearoa push for better naloxone access, we look for lessons across the ditch.