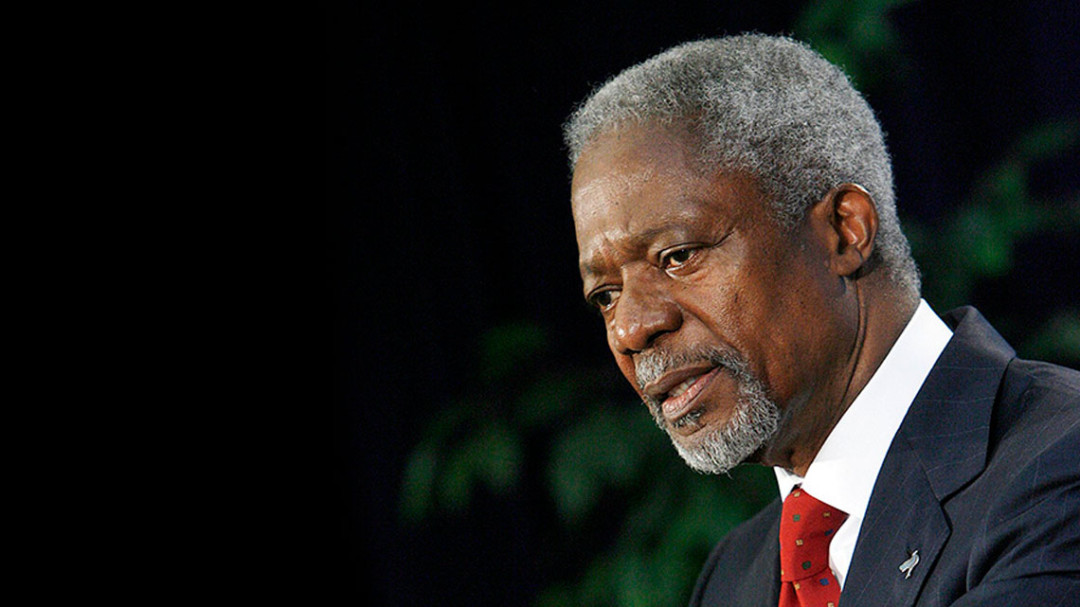

Q&A: Kofi Annan

Kofi Annan is chair of the Kofi Annan Foundation which works to promote better global governance and strengthen the capacities of people and countries to achieve a fairer, more secure world. He is a former Secretary General of the United Nations and Nobel Peace Prize laureate. Kofi Annan took time to answer questions from Matters of Substance about his role on the board of the Global Commission on Drug Policy.

Q. What is your position on the changes to law around cannabis in Colorado, Washington and Uruguay and the novel approach New Zealand is taking to new psychoactive substances? Do these herald an end to the War on Drugs?

A. A new policy approach is needed as the failure of the War on drugs has demonstrated that repressive approaches are not working. Despite vast expenditures, these approaches have clearly failed to effectively curtail supply or consumption. The outright and uniform criminalisation of drug use should be replaced by a public health approach.

The Global Commission on Drug Policy has called for governments to try new approaches, including the legal regulation of less harmful drugs such as cannabis, in order to undermine the power of organised crime and safeguard the health and security of their citizens. Countries should pursue an open debate and promote policies that effectively reduce consumption and which prevent and reduce harms related to drug use. A taxed and regulated market for currently illicit drugs is a policy option that should be explored with the same rigour and safeguards as any other. This option is now being tested in some countries, including New Zealand. By doing so, I believe that we can help break the endless cycle of violence, corruption and overcrowded prisons that has long characterised drug control regimes in many parts of the world.

Q. Like many other former world leaders, you started speaking openly about drug policy matters after you left office. What kind of pressures did you and other world leaders come under while in office, and do you think this will change with José Mujica’s openness and willingness to tackle drug policy issues head on?

A. For decades, public opinion supported a ‘tough on drugs’ approach. There was inertia in the drug policy debate, as policy makers understood that current policies and strategies were failing but did not know what to do instead. No elected leader wanted to touch this ‘third rail’. The work of the Global Commission on Drug Policy and others has helped break this taboo on drug policy. It is now possible to discuss alternative approaches. For the first time, a majority of Americans support regulating cannabis for adult consumption.

Leaders should take the opportunity presented by these shifts in public opinion to start implementing harm-reduction policies and public health strategies that can make a real and lasting impact on drug trafficking and consumption. All authorities – national and international – must recognise reality and move away from conventional measures of drug law enforcement ‘success’ (e.g. arrests, seizures, convictions), which do not translate into progress in communities.

There will be a special session of the United Nations General Assembly in 2016, which will provide a great opportunity for an honest and informed policy debate. Hopefully, from that debate will flow drug policies informed by evidence of what actually works in practice rather than what ideology dictates. The international conventions should be interpreted and/or revised to accommodate the robust testing of harm reduction, decriminalisation and legal regulatory policies.

Q. The strongest voices calling for reform of drug laws and policies are coming from the south, from nations most affected by the War on Drugs. What message would you give to those richer countries who continue to support the war on drugs approach, and is it time for them to take a back seat in this debate?

A. The wave of drug policy reform in Latin America is gaining further strength as leaders from countries like Colombia, Guatemala, Mexico and Uruguay have started implementing reforms. Since its creation, the Latin American Commission on Drugs and Democracy has called for the adoption of a new paradigm to deal with narcotics. This was taken further by the Global Commission on Drug Policy, which has advocated for an informed, science-based discussion about humane and effective ways to reduce the harm caused by drugs to people and societies.

The Organization of American States studied and evaluated current anti-drug policies in the hemisphere and explored new approaches and alternatives to strengthen and make them more effective. This resulted in a landmark report on drug policy in 2013, proposing different scenarios, including alternative forms of drug regulation.

As my own region, West Africa, has become a major transit and repackaging hub for cocaine following a strategic shift of Latin American drug syndicates towards the European market, I have convened the West Africa Commission on Drugs (WACD). The WACD is analysing the problems of trafficking and dependency in order to deliver an authoritative report and comprehensive policy recommendations on how to best tackle this growing menace to the region’s governance, security and development.

Drug trafficking is a global phenomenon. The development and implementation of drug policies should be a global shared responsibility. The UN drug control system is built on the idea that all governments should work together to tackle drug markets and related problems. This is a reasonable starting point, and there is certainly a responsibility to be shared between producing, transit and consuming countries (although the distinction is increasingly blurred, as many countries now experience elements of all three).

However, relatively rich ‘consumer’ countries need to acknowledge that their citizens’ demand for drugs is a direct cause of problems in transit countries. Many of these relatively wealthy countries have implemented progressive, health-oriented policies towards their own drug users. They should help to spread and fund evidence-based prevention, harm reduction and treatment to other, poorer countries that serve as transit corridors to their own drug markets.

Recent news

Reflections from the 2024 UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs

Executive Director Sarah Helm reflects on this year's global drug conference

What can we learn from Australia’s free naloxone scheme?

As harm reduction advocates in Aotearoa push for better naloxone access, we look for lessons across the ditch.

A new approach to reporting on drug data

We've launched a new tool to help you find the latest drug data and changed how we report throughout the year.