Drug harm ranking study reveals alcohol, methamphetamine are most harmful in NZ

The University of Otago’s Dr Rose Crossin has just gotten her hands on a recent edition of the Upper Hutt Leader newspaper.

The edition in question features a story about her newly released drug harm ranking study she co-authored with Professor Joe Boden:, under the headline “Alcohol named NZ’s most harmful drug by university research paper.”

Ironically, the paper chose to place a half-page ad for Thirsty Liquor directly below the article.

“I’m laminating [the newspaper] and it’s going on my wall,” Dr Crossin says, smiling.

One of my students sent me this today - says it all really! pic.twitter.com/5OyyGdANaj

— Dr Fiona Hutton (@hutton_dr) July 5, 2023

How the drugs were ranked

Although similar ranking studies have been conducted overseas, Dr Crossin's study is a first for NZ. The study also includes two new criteria developed to better incorporate a Māori worldview: spiritual and intergenerational harm. It also assessed the harm drugs cause to rangatahi aged 12 to 17.

Study co-lead Dr Rose Crossin

Rather than look at the harm from drugs in absolute terms, the study aimed to find a ‘realistic middle ground’ of harms relevant to most people who use drugs. It was therefore assessing harms based on New Zealanders with "typical" usage patterns of the 23 substances assessed.

Executive Director of the New Zealand Drug Foundation, Sarah Helm, says it was highly useful to have drug harm data in a local context.

She says it is well-known that our most popular legal drug, alcohol, causes a significant amount of harm to individuals and communities in Aotearoa. “It might surprise some people, but this study shows that there’s no relationship between legality and lower harm. In fact, it’s our drug laws that are causing a lot of the harm.”

Helm says it is important people understand that the study takes a broad and long term view of harm, including community, economic and even environmental damage. "This is not just a ranking of intrinsic toxicity. When you look at mortality alone a drug like fentanyl, for example, ranks much more highly."

When it came to ranking the drugs, Dr Crossin says the ones that caused the most contentious discussion in the group were cocaine, tobacco and fentanyl.

Cocaine was ranked as causing less overall harm in New Zealand than it did to people in the UK and EU studies. “We’re saying it’s less harmful because the people who use it and the way in which they use it had all of these other protective factors packed in around them. [In New Zealand] they’re not a vulnerable drug user, typically.”

For Fentanyl, Dr Crossin says at present there is very little of it in Aotearoa. “We covered this ranking in caveats. If we had more it in NZ, it would likely move up the ranking very fast,” she says.

Youth ranking

Dr Crossin acknowledges the challenges inherent in assessing drug harm for young people. The expert panel that assessed drug harm consisted entirely of adults.

Identifying a 'typical' young person who uses drugs, such as opioids, was another significant challenge. "With a small number of people who use, it's hard to draw conclusions," she says. 'How can we truly understand what a young user of these substances looks like?'

Dr Crossin notes the difference in the nature of harm between youth and adults. For young people, the majority of assessed drug harms centred on harms to self. In contrast, adult use was viewed as causing greater levels of harm to others and society. Dr Crossin explains this by saying, “If an adult loses their job due to drug use, it could potentially have a more widespread impact than if a young person between 12-17 were in the same situation."

Helm suggests that if the drug landscape changes, the ranking of drug harms could change as well.

“In an unregulated black market, we're vulnerable to global supply changes, and potentially more harmful substances may emerge. If we were to witness an influx of fentanyl or cocaine, for instance, these drugs could likely shift up the harm ranking,” she says.

The study concludes that current drug laws have contributed to the harm associated with certain drugs. One such policy is the criminalisation of drug possession and use. Therefore, the harm score for cannabis in New Zealand is likely higher than it would be in countries where cannabis is legal and regulated.

The case for changing our drug laws

Dr Crossin believes that the study’s findings strengthen case for law reform. "There are a whole bunch of harms that come out of a drug's legal status. We are causing harm." She says the study results strengthen the call for decriminalisation “at the very minimum.”

“As Professor Boden rightly pointed out, a whole bunch of these harms would be removed by legalisation, along with some really decent regulation. I don’t want to see a cannabis market that looks like our alcohol market in New Zealand – that’s clearly not going to reduce harm.”

Helm agrees with the need for reform. “When we rank drugs by their harm, the compelling evidence for drug law reform is glaringly obvious. It's past time to overhaul our drug laws and shift towards regulating substances based on the harm they cause, rather than leaving it to the black market.”

“Just as we've seen with tobacco, regulatory tools can significantly reduce harm," she says.

You can find out more about the study on the University of Otago website.

Recent news

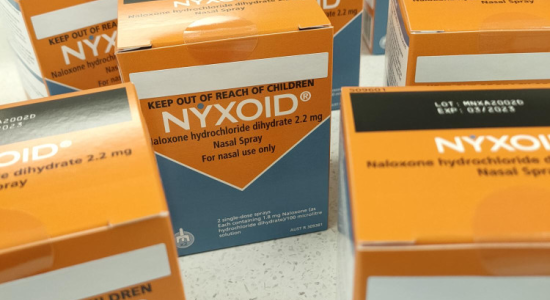

Expert Pharmac committee recommends funding for overdose reversal nasal spray

Public funding for a lifesaving opioid overdose reversal nasal spray is one step closer, with an expert committee saying that funding the medicine for use by non-paramedic first responders and people at high risk of an opioid overdose is a

Reflections from the 2024 UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs

Executive Director Sarah Helm reflects on this year's global drug conference

What can we learn from Australia’s free naloxone scheme?

As harm reduction advocates in Aotearoa push for better naloxone access, we look for lessons across the ditch.