New options to avert North American opioid crisis

Despite some valiant efforts to reduce drug harm, such as by safe-injection facilities, the body count is still growing in North America. Are new approaches and more resources needed? What form should they take? David Young investigates.

With one of North America’s densest populations of injecting drug users, Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside has the grisly distinction of being the Canadian epicentre of the opioid crisis. Young men here die 17 years earlier than men living in the city’s more prosperous west side.

But if Downtown Eastside is Canada’s crisis epicentre, it has also been ground zero of efforts to ensure that the response is evidence-based and focused on harm reduction. It was here that Sarah Blyth and volunteers from the Downtown Eastside market set up a tent, and a table in an alley behind their market in 2016, administering the overdose reversal drug naloxone. At first, they were breaking the law.

“I said I didn’t really care what the city [officials] or anyone else said because it just made sense,” says Blyth, now Executive Director of Vancouver’s Overdose Prevention Society. “There’s no way they could argue with it. People were dying here, in front of us. That’s just not something we can let happen.”

Perhaps surprisingly, today, those working with the epidemic in Downtown Eastside are calling for a brand-new approach, arguing that even an expanded harm-reduction response cannot resolve this crisis.

The North American opioid epidemic is so lethal that life expectancy in Canada has flatlined for the first time in 40 years, and in the US, it has actually fallen. It has its roots in the 1990s when Big Pharma aggressively lobbied doctors to dish out drugs like OxyContin that they wrongly claimed had no real addiction risk.

North American opioid prescriptions rose suddenly and rapidly. Opioid-based painkillers became a common remedy for conditions such as back pain and arthritis. Across North America, medical opioid consumption has more than tripled over three decades.

In 2010, OxyContin was reformulated to make it more difficult to abuse. The US and Canada issued guidelines for doctors to restrict opioid prescriptions.

These actions did little to stop the crisis in places like Downtown Eastside, because foreign-based drug cartels flooded North America with cheap heroin and synthetic opioids including fentanyl, a drug 50–100 times more potent than morphine. If getting hold of legal painkillers became more difficult, users were able to turn to cheap, readily available and far more dangerous street drugs.

Today, illegal narcotics are more readily available than ever before, and illegal drug distribution networks have expanded from inner cities into rural and suburban areas.

The reality that the drug market is so toxic is the biggest obstacle to overcome,"

says Donald MacPherson of the Canadian Drug Policy Coalition. Federal and state governments in the US and Canada have struggled.

In October 2017, President Trump declared the epidemic a US public health emergency, freeing federal funds and loosening some restrictions on treatment access. Millions of doses of naloxone have been distributed in the US, but the federal response otherwise has largely been based around law and order.

British Columbia declared a public health emergency a year before the US. With eventual support from the Canadian federal government – and playing catch-up with community actions like those from Blyth and other volunteers – British Columbia put harm reduction at the heart of its response to the epidemic.

“I would say that the response in British Columbia has probably been better than anywhere else in the country,” says MacPherson. He credits the momentum to a politically supportive government, a strong public health chief medical officer who declared the emergency and a history of grassroots mobilisation. “Most of what has been achieved was initiated by the community, by people organising.”

British Columbia eventually led the way in opening overdose prevention sites, also known as supervised consumption or injection sites, following the one set up in a back alley by Blyth, which was funded by online donations. Not a single person has died in the overdose prevention sites.

The province was also fast at distributing naloxone and moved to scale up substitution treatment (getting people on opioid replacement therapies like methadone and Suboxone) and to allow drug toxicity testing.

Still, MacPherson says that the response has now stalled. “It became patently obvious to everyone that this is not a situation where harm reduction, while important, is going to be a really major part of the answer to the crisis.”

That’s a view shared by Professor Mark Tyndall of the University of British Columbia, a Harvard-trained doctor of infectious disease and epidemiology. Tyndall has worked with drug addiction in Downtown Eastside ever since moving to Vancouver in the late 1990s after treating HIV patients in Kenya.

From 2014 until January 2019, he served as Executive Director of the British Columbia Centre for Disease Control (BCCDC). As head of the BCCDC, Tyndall once urged a local community group to set up a ‘pop-up’ overdose prevention site inside a tent and invite the press. He has co-authored dozens of peer-reviewed studies on the benefits of supervised injection sites.

More than anyone, he was at the forefront of advocating for evidence-based harm reduction. But today, based on his experiences in Downtown Eastside, he says that giving people safe spaces to use drugs is not going to turn the tide.

Protesters hold a sign reading "Stop prefentable deaths, safe supply now" and "No more drug war" - Marchers in a parade through downtown Vancouver in April called for “safe supply”. Photo credit: Peter Kim

“I’ve been working in harm reduction for 20 years or more in Vancouver, and what’s happened to us in the last three-and-a-half to four years with the disappearance of diverted pharmaceuticals and the appearance of fentanyl in my mind really changed the equation entirely. The harm-reduction work that we’ve been able to support and expand is really no match for people consistently injecting toxic drugs.”

It’s not that harm reduction hasn’t worked – Tyndall credits approaches like naloxone distribution and supervised injection sites with saving at least 1,000 lives each year in British Columbia. But he, MacPherson and many other campaigners in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside say even expanded harm reduction can do little more because the drug supply is so toxic. They say this requires far more expansive responses that actually focus on the supply.

“We’ve done the natural experiment of harm reduction in Downtown Eastside,” says Tyndall. “There’s supervised injection sites, everyone has naloxone, paramedics are all over the place reviving people, there are [clean] needles everywhere, but it just doesn’t help the fact that people are buying toxic drugs from back alleys, and it’s just a matter of time until they overdose.”

He says there is a need for a “delicate balance” between continuing to support evidence-based harm reduction, which continues to face a backlash (especially in the US), and “starting a new dialogue about the fact that we have to actually supply people with safer drugs”.

Blyth agrees that it is time for a rethink of the response to the epidemic – and for safer supply measures to be at the heart of the response. “I think we need to look at who this epidemic is really affecting and try and change the way we think about things, and we have got to be more compassionate.”

What would a more compassionate approach based around ensuring safety of supply actually look like? Various measures are promoted by campaigners. All are controversial.

One idea is for British Columbia to enact de facto decriminalisation of drug possession. This has the backing of the province’s current top health officer, Dr Bonnie Henry, who issued a 50-page report in April called Stopping the Harm: Decriminalization of People Who Use Drugs in BC.

The current criminal justice-based framework keeps people at home, not talking about their drug use, using alone and dying,"

Henry told a press conference. She outlined two ways the Police Act could allow the province to effectively choose not to prosecute drug possession. It would still be illegal to make and traffic drugs.

“What we’re talking about is alternative pathways for people who are caught with small amounts of drugs for personal use, where there are alternatives to incarceration.”

The problem, MacPherson says, is that “there is no consensus at the provincial level” on whether to take her advice.

In the meantime, advocates argue for other approaches to make sure injecting drug users have access to safer drugs. The Pivot Legal Society, based in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, went to court to fight for heroin-assisted treatment – a medical intervention in which prescription pharmaceutical-grade heroin is prescribed to people with long-term opioid dependency who have not responded to traditional treatments.

When the federal government banned heroin addiction therapy in 2013, Pivot took legal action on behalf of five patients from the 200-person SALOME study, which gave some drug users heroin. Pivot won an injunction protecting the research participants’ access to the therapy until trial. In 2016, the federal government gave up and repealed the law.

Elsewhere in Downtown Eastside, the Providence Crosstown Clinic has been providing chronic injecting drug users with injections of medical-grade heroin for years as part of two landmark longitudinal research projects.

Blyth thinks that she and her team should be able to provide opiates to users. “Ideally now that overdose prevention sites are set up, we could hold onto prescriptions and give them out to people. I can hold people’s medications – and meds also include opiates.”

For Tyndall, it’s important that heroin distribution is moved out of the medical realm. “In Canada at least, we’ve trained all our physicians that these drugs are bad. To reverse that idea now is difficult. We need to get it out of medical hands and also give up the idea that we can somehow get enough doctors to undertake one-on-one assessments” every single time someone injects. He adds that many people who use drugs would prefer not to be observed and supervised so avoid clinical settings.

A reporter interviews Donald MacPherson, who is wearing sunglasses and a t-shirt reading "Raise shit!" - Donald MacPherson, Executive Director of the Canadian Drug Policy Coalition, advocates for a full range of harm reduction responses. Photo credit: Peter Kim

Tyndall is leading a pilot programme, which grew out of the SALOME study. In the study, he is giving Downtown Eastside’s most at-risk drug users a regular allotment of hydromorphone pills (a powerful prescription opioid), which they can use elsewhere instead of buying potentially toxic street drugs.

“We need something that is cheap and easily accessible and people can take with them,” says Tyndall. He wants to go further. Right now, in the first stage of his study, patients are still required to come to a clinic to pick up their drugs from medical staff.

Tyndall’s idea – not yet fully approved and funded – for the trial’s second stage is to do away with the clinic environment and with the medical staff altogether. He gained international attention for his proposal to distribute the drugs in opioid vending machines.

A Canadian tech company, Dispension Industries, which had been working on vending machines to distribute cannabis, has designed a prototype: a 350-kilogram kiosk that uses biometric scanning to identify approved users.

But the challenges are less technical and more political. Organisations representing both pharmacists and doctors have expressed concern. Tyndall unexpectedly lost his BCCDC leadership role in January in a move that created press speculation that he had been too outspoken. (He continues to lead the research.)

In the meantime, some activists in Downtown Eastside are reportedly considering engaging in civil disobedience to illegally buy and provide safe supplies of heroin – an approach that MacPherson describes as “very, very high risk”.

“In harm reduction, people started handing out syringes when that was illegal; people set up supervised injection sites when that was illegal. The precedent globally is that people break the law to provide life-saving health services, and governments follow.”

Tyndall says he knows many doctors who “stray” outside rules on opioid prescription in order to ensure users aren’t forced to rely on potentially lethal street drugs.

In April, hundreds marched through downtown Vancouver calling on the government to offer pharmaceutical alternatives to unknown substances purchased on the street. The march for safer supply attracted drug users, advocates and community organisers.

“We’ve been talking about this for years,” Dean Wilson, former President of the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users, told a journalist. “For the last four years, we’ve been dying in numbers like we were dying of HIV. The solution is really simple: prescribe.” He accused politicians of not caring.

I just don’t believe in government any more. They all lie. And they’re all full of shit."

For Blyth, ensuring users have safer supply would be good for all of society. “I hear the argument, ‘Why would we do this with taxpayer money?’ Because it would save money in the long run. If you give people money, it’s not going to cost as much in break-and-enters, in survival sex trade, in trauma, in all the things that people do in a desperate situation.”

Wherever British Columbia goes next, it is entering uncharted territory. “The fentanyl epidemic is largely a North American thing,” says Tyndall. “Other countries have had it a little but nothing like here. As we stumble along pushing harm reduction, the toxic drug supply and the high numbers of overdoses have changed the equation for us, and people who understand that jump on the bandwagon of safer supply.”

MacPherson worries that the crisis could get even worse. “It depends on what is going on in the unregulated drug market. It’s really hard to draw a line, because even with all of the harm-reduction work going on, it’s still only covering a minority of the population. The people who are dying, they are dying alone.” Alone and in great numbers.

- Main image photo credit: Travis Lupic

Recent news

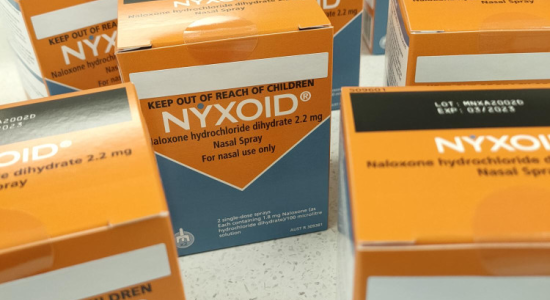

Expert Pharmac committee recommends funding for overdose reversal nasal spray

Public funding for a lifesaving opioid overdose reversal nasal spray is one step closer, with an expert committee saying that funding the medicine for use by non-paramedic first responders and people at high risk of an opioid overdose is a

Reflections from the 2024 UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs

Executive Director Sarah Helm reflects on this year's global drug conference

What can we learn from Australia’s free naloxone scheme?

As harm reduction advocates in Aotearoa push for better naloxone access, we look for lessons across the ditch.