“We’re not here to judge.”

At Auckland’s Aorere College, it is rare for young people to be permanently kicked out of school for drug-related incidents. Instead, students are supported to change while remaining within the school community. Keri Welham explains.

Mark is 16 years old with a tidy uniform and a proud smile. The year 12 Aorere College student works part-time, plays rugby and tries to steer clear of trouble at school.

But there was a time earlier in his secondary education when he got into trouble for using “weed and alcohol”. He turned up to class stoned – “just for fun”.

The student believes other schools would have scratched him from their roll, but Aorere College stood him down for three days. As a condition of his return to school, he was made to attend a course run by Odyssey House. It educated him about issues with drug and alcohol use and offered him tools, such as strategies for resisting peer pressure situations.

The investment in him, and the school’s decision to keep him on the roll, illustrated to the student that he was valued. He believes his teachers truly want him to finish school, and he’s grateful his education wasn’t derailed by what turned out to be a fairly short-lived phase of experimental drug use.

Mark is one of 1,550 students at decile 2 Aorere College in Papatoetoe, Auckland. The school is close to the international airport and its motto, Virtus Caelum Recludit, translates to ’character opens the way to the heavens’.

While most Aorere students have home lives that are indistinguishable from those of Kiwi kids throughout the country, the school serves a community of particularly high social need.

A small number of students suffer acute financial, social and emotional deprivation. For this group, gambling addictions, hunger and poverty-related illness are common. Many weeks, at least one parent in the school community dies as a result of poor health.

And from 8.40am till 3.10pm… this is a place that they know that they can be safe and not worry about the concerns and the issues that are going on at home. The kids know we’re not here to judge them.

Helen Perez

There are 13-year-old students with babies and many families paying off school uniforms at $5 a fortnight. Some students live in households where three families cohabit under one roof – victims of Auckland’s rampant housing market and the crippling rents that follow – while others have been found sleeping in cars with their families.

A few are born into gang families and coached in crime from a young age. Some live in households where the proceeds of drug sales are the main source of income.

Counsellor Debbie Binney says it is “normal” for some students to smoke weed with their parents or grandparents or be tasked with selling it on behalf of their family.

“It’s normal. For so many of our kids, it’s normal.”

Social worker Helen Perez says, for those with the most dysfunctional home lives, Aorere College is their “safe haven”.

“And from 8.40am till 3.10pm… this is a place that they know that they can be safe and not worry about the concerns and the issues that are going on at home. The kids know we’re not here to judge them.”

Tom Brown is Director of the Aorere College Student Services and Engagement Centre. He says the school has worked hard at creating an atmosphere where young people feel supported – a philosophy consistent with the first goal of the Whole School approach – and Aorere staff now increasingly help students with difficult personal problems usually considered beyond the notice and capability of a school.

Young and experienced staff often need to be educated in the Aorere approach to discipline. Brown says new teachers can over-react to behaviour issues and quickly escalate a situation that, in the context of the issues the school faces, is fairly minor. Educating newer staff to pick their battles, with a view to helping shape well rounded students capable of making good choices, is key to maintaining the school’s culture of support.

Tom Brown

Brown says students respond to being trusted and treated as individuals. If a student breaks a rule, but it’s in the context of a small blip on a path of steady improvement, the school might opt to put them ’on notice’ rather than deliver more severe consequences. Many students will learn more from that support and forgiveness, and the opportunity to continue on a positive path, than if they’d been punished.

“Work with the kid,” Brown says, “not with the rules and regulations.”

Brown helps co-ordinate student access to a variety of community services, from mental health care to Police support. The school uses drug dogs to educate students and warn off the few that are tempted, but not urine testing, which the school’s nurses find unreliable and expensive. If a young person is found using drugs at school, they are generally stood down and a reintegration programme is drawn up to support them with their return to school.

Claire Ferguson has been a long-time counsellor at Aorere. She says, in the early 2000s, the school was as harsh in its discipline as any other school. Today, the climate within the school is one of support for young people falling short of expectations.

“I’m thinking of a couple of kids that, at any other school, they’d have been history.”

She says the move to a restorative approach at Aorere has coincided with an improvement in the school drug problem. She says there are noticeably fewer drug problems than during times of more punishing consequences.

A year 12 student called Richie has often been in trouble for fighting but never for drugs. If he ever had a problem with drugs, he says he’d talk to the school counsellors. He says he trusts them.

Another year 12 student, Samuel, is engaging, bright and a little shy.

In year 9, his first year of secondary school, Samuel attracted attention for using cannabis.

“I got snapped taking it, and [I was] stoned in class.”

He wasn’t expelled; in fact, he didn’t even appear in front of the school board.

“They just like sat me in one of the counsellor’s rooms and waited for me to sober up and then they had a talk with me.”

Samuel’s previous misdemeanours range from violence to wagging, but this year, he’s turned a corner and is keeping out of trouble. When asked to imagine his life if he’d attended a school with a ’zero tolerance’ policy towards alcohol and other drugs, he’s quick to reply.

“I’d probably be like one of those people that quits, eh, that are like struggling with life and that.”

Samuel wears a black school jacket, short hair and a giant smile. He is well known to school staff – it’s clear the absence of punitive measures in the school hasn’t enabled him to escape notice. Teachers and support staff keep a close eye on him. He laughs: “They won’t leave me alone, eh.”

Photo credit: Peter Meecham

Recent news

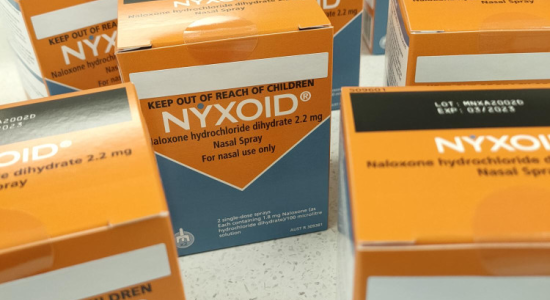

Expert Pharmac committee recommends funding for overdose reversal nasal spray

Public funding for a lifesaving opioid overdose reversal nasal spray is one step closer, with an expert committee saying that funding the medicine for use by non-paramedic first responders and people at high risk of an opioid overdose is a

Reflections from the 2024 UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs

Executive Director Sarah Helm reflects on this year's global drug conference

What can we learn from Australia’s free naloxone scheme?

As harm reduction advocates in Aotearoa push for better naloxone access, we look for lessons across the ditch.