Students skip suspension, get support instead

It’s in the playgrounds, on the sports field and in the dean’s office where many teenagers learn about making good choices, asking for help and the consequences of their actions. Over the next few issues of Matters of Substance, we will look into new approaches to protecting young people from drug-related harm being adopted by New Zealand schools. In this issue, Keri Welham outlines the Whole School approach and, on page 24, shares what is happening at Aorere College in Auckland.

Ben Birks Ang says schools have three clear opportunities to signal their approach to alcohol and other drug use.

The first is in educating young people about the effects of substance use and good decision making, as required by the national curriculum. The second is in the establishment of a school climate that focuses on student wellbeing. The third is in a school’s response to a breach of its rules.

Birks Ang is National Youth Services Adviser at the New Zealand Drug Foundation and Odyssey House. He says students should only be removed from school because of behaviour related to drugs or alcohol as a “last resort”.

Education Ministry figures released in 2014 show “drugs (including substance abuse)” was the most common reason for a young person to be expelled from a New Zealand secondary school.

“Removing a student from school can have a large negative impact on a young person’s life trajectory, because there are multiple benefits associated with remaining engaged with education,” Birks Ang says.

Unsurprisingly, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development data clearly links educational attainment to higher employment rates, longer life expectancy and enhanced skills.

Keeping young people at school doesn’t mean they avoid consequences for unacceptable behaviour, but it does mean the school approaches the alcohol or drug use as a health issue and seeks appropriate care and treatment for the young person.

Half of the people in New Zealand who experience alcohol dependence would have developed it by the time they were 19 years of age.

Schools favouring alternatives to exclusion from school are increasingly working to philosophies consistent with the Whole School approach (see sidebar). The first aim of the approach is creating a school environment that promotes wellbeing and positive social interactions. Supportive school environments are recognised as a vital tool in creating protective forces for young people.

Birks Ang says young people recognise their school as supportive when it encourages them to seek help, when it is clear there will be consequences for unacceptable behaviour but mistakes are seen as learning opportunities rather than opportunities for punishment and when they can have balanced discussions with adults at school about the pros and cons of risk-taking behaviours, such as lingering tension from fighting at a weekend party, and receive sound advice.

Birks Ang’s role with Odyssey House takes him into various New Zealand secondary schools to help address the needs of young people battling problematic substance use or dependence. He says students in schools with punitive or zero-tolerance regimes have to work much harder to overcome problem drug or alcohol use. By comparison, students at schools with restorative practice models view teachers as key support people and are empowered for the work ahead.

The signals to move towards restorative practices may seem clear, but Birks Ang says he still sees ambivalence towards the first plank of the framework: the challenge of creating a supportive culture in a school.

Many schools appear to be focusing on the last plank, accessing professional treatment for high-needs students, “and slowly working backwards”.

Martin Henry is an advisory officer with responsibility for pastoral issues with the New Zealand Post Primary Teachers’ Association (PPTA).

Henry says Birks Ang is right about schools focusing disproportionate energy on crisis response rather than school culture.

“The first step is always to flail your arms.”

Wellbeing is a state of mind – a continuous journey – and there is no specific resourcing available to help a school develop it. Instead, many schools tend to invest resources into crisis response – even though Australian research has shown a focus on school climate and student connectedness may be “equally, if not more effective in addressing health and problem behaviours than specific, single issue focused education packages”.

Henry says most schools are moving in a positive direction. Positive Behaviour for Learning, an Education Ministry programme available to all schools, is helping show schools how to build positive environments. Meanwhile, a PPTA and Teachers’ Refresher Course Committee conference on Wellbeing in Schools is scheduled for 6–8 October in Auckland. It will include a workshop on Whole School approaches.

Henry says the media’s fixation with bullying, and society’s warranted concern about its impact on young people, has drawn attention away from the significant impact of drug and alcohol use among teenagers.

“Drug and alcohol use and its impact on learning is arguably the biggest issue in the pastoral realm,” Henry says.

Recent research shows 24 percent of those surveyed meet the criteria for binge drinking, 23 percent have tried cannabis, and 11 percent use drugs to very high levels and are therefore predisposed to other health risks such as unsafe sex and obesity.

The Education Review Office (ERO) has shown a sharp interest in wellbeing. It released a report in February this year, titled Wellbeing for Young People’s Success at Secondary School, which says the most effective schools understand students need opportunities to learn and take risks in a safe environment.

In a 2014 report, ERO assessed the culture of nine schools ranked decile 5 or below. The schools explored alternatives to punitive measures.

The report says: “Once students are excluded or expelled it is often extremely difficult for them to re-engage with their education, have a sense of self-worth, and achieve the skills and qualifications that will help them in the future.”

In 2013, ERO released draft evaluation indicators for student wellbeing. One of the indicators reads: “All staff integrate a focus on student wellbeing alongside a focus on student achievement.”

Henry says this sentiment is key.

“Success is not just about the academic results,” Henry says.

“It might just be about keeping the kid in school or the kid not going to jail [in] the next 40 years.”

University of Auckland research has shown the main barriers to young people accessing health are hoping that the problem will go away not wanting to make a fuss and lack of transport.

Schools are increasingly overcoming these barriers by acting as unofficial community hubs, bringing highly skilled professionals into the school to work with young people in an environment where the young person feels safe. This takes hours of liaison and co-ordination on top of a dean or deputy principal’s existing workload.

Schools are keen to do the work, says PPTA Executive member Jack Boyle, but need effective policy to direct their well meaning efforts and funding to ensure support of high-risk students doesn’t come at the expense of their peers’ needs.

Despite these frustrations, Boyle says there is a lot of optimism in secondary education, and the ERO’s focus on wellbeing is a welcome development.

The teaching of wellbeing issues, such as developing skills to think critically and self-manage, is generally limited to the health and physical education curriculum, which is not compulsory after year 10. However, Birks Ang says it’s generally beyond year 10 (13- and 14-year-olds) that many young people begin to encounter the situations for which they need the resilience and strategies taught through health education.

The mid-teens are not only a vital time for building up the skills and reserves of young people but also for intervention.

Birks Ang says dependencies, which could cause a lifetime of pain, are often developed during this time.

“Half of the people in New Zealand who experience alcohol dependence would have developed it by the time they were 19 years of age. Supporting those young people to make changes now would make a significant difference in the coming years.

“To be able to respond, each school needs to have prepared in advance and be resourced to support students with alcohol problems.”

Recent news

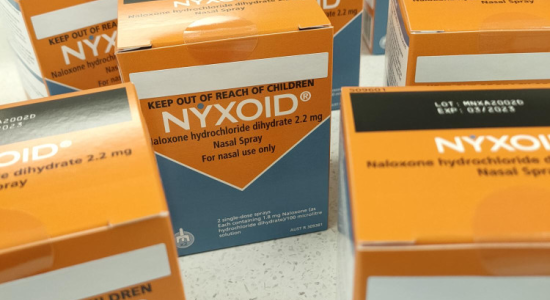

Expert Pharmac committee recommends funding for overdose reversal nasal spray

Public funding for a lifesaving opioid overdose reversal nasal spray is one step closer, with an expert committee saying that funding the medicine for use by non-paramedic first responders and people at high risk of an opioid overdose is a

Reflections from the 2024 UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs

Executive Director Sarah Helm reflects on this year's global drug conference

What can we learn from Australia’s free naloxone scheme?

As harm reduction advocates in Aotearoa push for better naloxone access, we look for lessons across the ditch.