The Retreat

On a leafy Ōtāhuhu street just off Auckland’s Southern Motorway is a new recovery centre called The Retreat. Utilising a ground-breaking residential treatment model developed in the United States, The Retreat harnesses the will and experience of volunteers from the recovery community to deliver its programme. Keri Welham reports.

At the end of an otherwise plain little street, a gap in the trees offers a view of the Tāmaki Estuary and the factories of East Tāmaki. This is Avenue Road East in Ōtāhuhu, and Craig LaSeur thinks it’s the perfect location for his suburban sanctuary.

The American clinician has relocated Down Under to run the New Zealand version of The Retreat. The 10-bed facility opened in April, and by early June, it had five graduates and two clients in residence. Each client checks in for 30 days at a cost of $5,850 plus GST. The substantial saving, compared with many other residential treatment options, comes courtesy of The Retreat’s major point of difference – its programme is delivered wholly by volunteers from the recovery community.

The volunteers are hand-picked for their message of hope, their own solid recovery and their ability to connect with guests. While clinicians oversee the programme and control induction, the volunteers run workshops, chapel, music nights and onsite fellowship meetings. This model saves money, making treatment more accessible for those with limited financial means, and allows guests to see what long-term sobriety looks like up close.

In the women’s wing is a guest who is in her 30s. Her bed is made, a book from the vast body of 12-step literature lies on her quilt, and two gorgeous girls beam out of a photograph propped up on a wall.

The bathrooms here look every bit like they belong in the rest home this once was. The doorways are wide, the fixtures are reminiscent of a 1980s school ablution block, and there’s an excess of beige. But the bedrooms have particularly plush looking single beds – a comfort factor the trustees refused to scrimp on – and are decorated in modern, welcoming tones.

There are 10 guest beds, with the capacity to add another 16 eventually. In the reception area is a photograph of the 1958 Junior All Blacks. Next to Sir Colin Meads, in the row behind captain Sir Wilson Whineray, is Roger Green. The well-known and respected addiction practitioner has worked tirelessly over many years to make this centre a reality, and despite being in his 70s, he joins LaSeur as the other clinician on The Retreat’s team.

The kitchen is a simple set-up where guests prepare their own breakfast. The chef, himself in recovery, makes lunch and dinner, and the guests, staff, volunteers and occasionally trustees eat together.

LaSeur says guests are nervous on their first day. The 12-step culture comes wrapped in a new language of terms and ideas. Often, the only sounds are feet padding down a hallway or pans clanging in the distant kitchen. The television is only turned on one night a week. The goal is a quiet, meditative atmosphere.

In the men’s wing is a guest in his 50s. Laid out on his bed are neat piles of reading material.

At one stage, he passes LaSeur’s office, and the two bounce off each other.

“What are you up to,” LaSeur says, with a warm, exuberant smile.

“Trying to get better,” the man calls out, as he strides on by.

LaSeur has been sober 15 years. He went to his first 12-step meeting, on a beach in Hawaii, when he returned from serving in Desert Storm with the US Marines.

“You’re not allowed to do crack in the Marine Corps,” he says, deadpan. He was facing drug charges in a military court, the collapse of his marriage and the crumbling of his career, but he wasn’t ready to change. He spent 28 days in jail, his wife left him, and he exited the Marine Corps before he could be kicked out.

Six years later, he was 28, working as a cook in Chicago and addicted to crack and alcohol. He had been sleeping in a park with his rottweiler Magnum. One night, he called his mother and she said, “I love you” and hung up. On a Wednesday afternoon soon after that phone call, he woke up on a cocktail waitress’s couch, saw the paraphernalia of another night of drugs and drink, realised it was 2pm, called his stepfather and said he was ready.

His parents had been waiting for that phone call a long time. They had a bed waiting for him, a phone assessment booked with the famed Hazelden addiction treatment centre, and he was on a plane to Minnesota 48 hours later.

Today, LaSeur is 43, married to Patricia and they have two sons. Once sober, LaSeur gained a sociology degree and studied at the Hazelden Graduate School of Addiction Studies. He worked in detox, then at Hazelden as a clinician, then at a sanctuary in the Washington State rainforest where he ran a programme for 16- to 24-year-olds with chemical addictions. The challenge of building a recovery centre from scratch was enough to lure him to New Zealand.

LaSeur follows the Blues rugby team, is an enthusiastic new recruit to Facebook and walks around with a colleague’s tiny mutt Froggy tucked under his arm. He has the height of a basketballer, a youthful face, a strong handshake and a deep enthusiasm for catering to those who can’t afford expensive treatment.

“Having something that’s affordable, there’s something about that that plucks my spirit.”

LaSeur says The Retreat doesn’t offer counselling.

“We are not an expert-driven model.

“It’s a practical programme of action rather than reflection and self-pity.”

He makes sure the guests are safe, well fed and having a good time (by which he means, getting sober).

“I kind of think of myself as a bed and breakfast manager.”

LaSeur says the volunteer-led model of treatment on offer at The Retreat is not for everyone. He believes it would never work for teenage males with chemical addictions as they need much more structure and discipline. It wouldn’t have worked for him, LaSeur says, as his crack addiction necessitated a complex detox and clinical expertise.

And so, every week, LaSeur refers some potential guests to other facilities.

“There are those individuals who need that clinical environment, and there are also those who don’t. We are not a hardcore programme.”

The Retreat is run as a charitable trust. If there is ever a surplus of funds, it will be used on scholarships to further discount the fee.

LaSeur says recent independent outcome studies of guests at The Retreat in Minnesota have shown long-term sobriety results as good as – and sometimes better than – those seen in much more expensive programmes.

LaSeur used to volunteer at The Retreat in Minnesota, which is situated in the cathedral-like Wayzata Big Woods just west of Minneapolis. And so, the suburban setting for New Zealand’s version of The Retreat concerned him when he first looked up the address on Google’s Street View. What if the neighbours had regular parties and the sounds echoing over the fence upset the sanctuary-like atmosphere of The Retreat? What if passers-by were forever trying to get a gawk at the latest arrivals?

As it happens, Avenue Road East is quiet, and the neighbours are a non-event. The beige and brown blocks of the former rest home and children’s hospital nestle in between modest homes and a plant nursery. There is no Betty Ford-style glitz, no high hedge, no exclusive address or sense of isolation from the world – and to LaSeur’s mind, that’s part of the magic.

With its unexceptional appearance, geography and atmosphere, The Retreat offers a picture of everyday suburban sobriety.

“Here’s this little gem in South Auckland,” LaSeur says. Froggy scuttles around his feet. Wheelie bins line the curb for rubbish day. Autumn leaves create perfect circles of colour at the feet of smooth grey trunks. And for two people sitting down to lunch within the safety of these walls, a rebirth is under way.

Keri Welham is a Tauranga-based writer.

Recent news

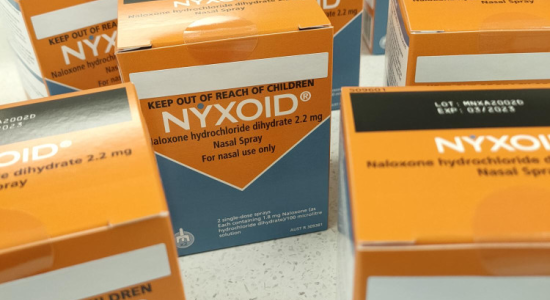

Expert Pharmac committee recommends funding for overdose reversal nasal spray

Public funding for a lifesaving opioid overdose reversal nasal spray is one step closer, with an expert committee saying that funding the medicine for use by non-paramedic first responders and people at high risk of an opioid overdose is a

Reflections from the 2024 UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs

Executive Director Sarah Helm reflects on this year's global drug conference

What can we learn from Australia’s free naloxone scheme?

As harm reduction advocates in Aotearoa push for better naloxone access, we look for lessons across the ditch.