Viewpoints: Looking back to 1975 law reform

Four decades ago, the Bill that would become the Misuse of Drugs Act 1975 was making its way through Parliament. Politicians, experts, commentators and the public were all fervently debating the merits of drug policy and enforcement.

A lot has changed since then. New substances have come and gone, jurisdictions overseas have moved to legalise some drugs, research has changed the way we think about addiction and treatment and a Law Commission report has recommended sweeping changes to the law.

Cameron Price trawled through Hansard at the Parliamentary Library and delved into back issues of student rags and the Evening Post at the National Library to shed light on the arguments for and against the Misuse of Drugs Act all those years ago. Have they stood the test of time?

Aye

UPDATING OUTDATED LAW

The aim of the Bill, according to Health Minister Hon Bob Tizard, was to “consolidate and amend the law relating to narcotics”. The legislation replaced the Narcotics Act 1965, in part because the old law was outdated and didn’t allow for appropriate responses to the changes. The Bill extended the controls on narcotics to new psychotropic drugs. ’Narcotics’ was changed to ’controlled drugs’ to reflect the widened scope of the new law.

The Bill also brought New Zealand into line with international treaties. “The Bill also fully implements this country’s obligations under the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs and the Convention on Psychotropic Substances to which New Zealand is a party.” The two United Nations conventions, passed in 1961 and 1971 respectively, governed the production and distribution of dependence-producing drugs both nationally and internationally. These conventions were not self-executing, so New Zealand had to change its law to comply.

IMPLEMENTING RECOMMENDATIONS

The law was based on the Blake-Palmer report, which was the culmination of a review by the Board of Health to examine drug abuse in New Zealand. The review ran from 1968 to 1973 and was headed by Deputy Director-General of Health Geoffrey Blake-Palmer.

Among other things, it recommended a “single new Act to control all drugs and similar substances (apart from alcohol and tobacco) that had significant potential for misuse”. There were three main recommendations. One was that the relative potential for harm of individual drugs should be taken into consideration in prosecuting and sentencing offenders. This formed the basis of the ’ABC’ class system of drugs, where different penalties apply according to how the drug in question is scheduled.

The report warned of the futility of drug laws operating in isolation from comprehensive treatment programmes and a robust multi-sectoral approach. It contained progressive recommendations concerning prevention, treatment and options for diversion of young offenders away from the criminal justice system. These recommendations weren’t adopted in the law.

Another recommendation was that punitive measures be focused on the supply of drugs and not on possession. The report argued that addiction and drug misuse was primarily a psychological and health issue rather than one of criminal justice.

CULTURE WAR

The cultural and socio-political context in which the Bill was debated was far removed from that which we have today. Illicit drug use was associated with the ’hippie’ counter culture and was concentrated almost exclusively among those living at society’s margins. Unlike today, where most people have tried cannabis or other drugs themselves, many got their information from inflammatory media articles. The main drugs used at the time (cannabis, cocaine, opiates, LSD) were relatively novel: aside from cannabis, the drugs in circulation had only been synthesised in the preceding century.

Hon Frank Marshall, Leader of the Opposition, claimed that “the upsurge in the use of drugs is something we have not been accustomed to in this country”. For instance, in 1966, there were only 28 drug offences recorded, while in 1974, there were 1,500. Information was scant. Originally, there was to be a clause that reduced the penalties specifically for cannabis, but the government wasn’t able to assess a report claiming that it was harmful in time to vote on the Bill, so it was left out. Addiction, both chemical and psychological, was poorly understood. Data on drug use was insufficient, and therefore, many relied on anecdotal accounts of the problem.

Internationally, the mood was prohibitionist and punitive. Richard Nixon had declared the War on Drugs just four years previously. This mood is evident in the language used in the debates in the House: drug use is “a cancer” and a “social disease”; the problem needs to be “attacked”.

CRACKING DOWN ON DEALING

According to speeches made in the House, “the Bill places the emphasis on action against the pedlar, the pusher or the traffickers”. In the opinion of many MPs, “it is the source of supply that must be attacked now, and it must be the subject of sustained attack in the future”. Penalties for those who dealt in drugs reflected the magnitude of operations: the quantity sold, the risk profile of the drug, its source (importation or home-grown) and the terms of the transaction (cash transfer or gifting) were all factored in to sentencing.

The law also reversed the onus or burden of proof for possession with intent to supply if an individual was caught with a certain minimum quantity of the drug. Police were also granted powers of search without warrant of property and of person. These two measures were supported strongly by politicians at the time but have since come under scrutiny.

YOUNG PEOPLE

The major theme of speeches was that “we need to protect our young from this social disease”. Mention was made of media reports that claimed huge increases in drug use by high school children. Youth were portrayed as victims of the counter culture, with its absence of morals and sense of decorum.

Intertwined with this argument was the assertion that cannabis is a ’gateway’ drug. “The idea that marijuana is harmless is its greatest danger, because the users of soft drugs tend to graduate to hard drugs.”

Noes

ALL AYES

There was surprisingly little opposition to the Bill. It was introduced and supported by the liberal Labour Government. Opposition National Party MPs were clear in their support for the Bill from the beginning.

Criticism mostly came from those who made submissions to the Select Committee, as well as selected interest groups and commentators, so the bulk of the debate in the House of Representatives focused on the minor details of the law rather than whether there should be a law at all or whether a drastically different approach should be taken.

In fact, the National Party often argued that the law should go further. Hon Lance Adams-Schneider said, “My colleagues and I see a question mark about any reductions in penalties.”

There were minor quibbles: the title of the Bill, which was originally the Drugs (Prevention of Misuse) Bill, was changed halfway through its progression to the Misuse of Drugs Bill. This new name echoed the UK’s Bill, which had recently passed. National was also disappointed it didn’t get to co-draft the Bill; Labour drafted and introduced the Bill itself.

TREATMENT

The Blake-Palmer report stressed the importance of treatment in dealing with the issue of drugs. In the House, MPs said that, without treatment, “there is little, if any, chance of halting, let alone reversing, the steady escalation in the misuse of drugs”.

As a result of this focus, a rider was attached to the Select Committee’s report that read: “We are concerned at the need for increased facilities for the prevention, treatment and rehabilitation of people misusing not only drugs controlled under this Bill but also alcohol and tobacco.”

After considering the report, one MP remarked that “to accept the rider and do nothing about it would be grossly wrong”. Unfortunately, warnings about the futility of drug laws operating in isolation from comprehensive treatment programmes and a robust multi-sectoral approach were well founded.

TOO PUNITIVE

Some of the most vocal opponents to the law were students. The New Zealand Union of Students’ Associations (NZUSA) was particularly against it. In its submission, it referred to the “malicious hoodlums masquerading under the guise of the Drug Squad” and said it was “very concerned at the manner in which the Police sometimes go about apprehending drug offenders, especially in their use of paid informers and undercover policemen”.

NOT SUPPORTIVE ENOUGH

The Blake-Palmer report posited that “drug abuse is more a psychiatric than a pharmacological problem” and recommended a psychiatric assessment of every drug offender coming before the court. Although support for this idea was expressed by politicians – It is agreed that punitive law alone cannot succeed in countering the problem, and long-term results can best be obtained through education, treatment and rehabilitation” – this was not adopted in the law.

The NZUSA expressed concern that too much focus on supply and continued prohibition meant users would be stigmatised. “A more humane attitude should be shown towards individuals addicted to any drug. They should be regarded as sick people in need of treatment. The stigma of criminality can interfere with rehabilitation.”

SMOKING AND DRINKING IMMUNE

Much was made of the fact that tobacco and alcohol were not covered by the law. The Member for Hawke’s Bay lamented media distortions in portrayal of illicit drugs, leading the public to believe that cannabis, heroin and cocaine were causing the most harm. “Whereas in new Zealand the major problem is the misuse of alcohol which is by far our greatest health and social problem.” The NZUSA agreed with this sentiment, saying “NZUSA finds it hypocritical for society to treat marijuana, alcohol and tobacco and the respective people who use them, as differently as they have done in the past.”

Recent news

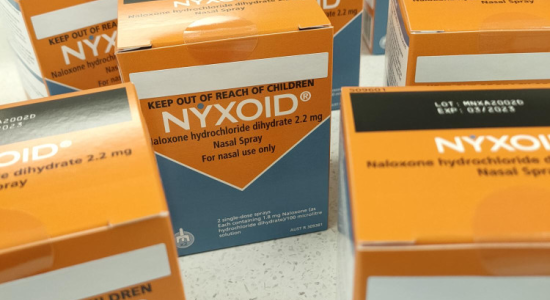

Expert Pharmac committee recommends funding for overdose reversal nasal spray

Public funding for a lifesaving opioid overdose reversal nasal spray is one step closer, with an expert committee saying that funding the medicine for use by non-paramedic first responders and people at high risk of an opioid overdose is a

Reflections from the 2024 UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs

Executive Director Sarah Helm reflects on this year's global drug conference

What can we learn from Australia’s free naloxone scheme?

As harm reduction advocates in Aotearoa push for better naloxone access, we look for lessons across the ditch.