Johann Hari on his film about Billie Holiday and the war on drugs

On the eve of the NZ release of The United States vs Billie Holiday, Russell Brown talks with Johann Hari about the movie, the global trend towards compassionate drug policy, and what's next for reformers.

'Black Hand', the second chapter in Johann Hari's 2015 book Chasing the Scream: The First and Last Days of the war on drugs, is the one that stays with most readers. Hari's gift for storytelling lights up an unfamiliar context for a beloved cultural figure, the jazz singer Billie Holiday – that of her problems with heroin, alcohol and other drugs.

He entwines Holiday's story with that the of the man who persecuted her until her early death, federal Narcotics Commissioner Harry Anslinger, in a way that sets out the key elements of the book: the connections between drug addiction and trauma, the drug war and racism, and the unfathomable cruelty that the dream of of a drug-free world can permit.

The chapter has now been adapted into a movie, The United States vs Billie Holiday, which opens in New Zealand cinemas on April 22. American reviewers have been as one in praising Andra Day's stunning performance in the lead role, but most have been less enthused with the film overall. Some seem affronted at its presentation of the more difficult side of a singer they have absorbed into their own cultural lives.

There are very few people who can hear the story of Billie Holiday and think, I don't care if she lived or died."

Old black and white photo showing Harry Anslinger during a drug bust - Federal Narcotics Commissioner Harry Anslinger. Photo courtesy of H J. Anslinger papers, 1835-1975 (bulk 1918-1963), HCLA 1875, Special Collections Library, University Libraries, Pennsylvania State University.

Hari, who was an executive producer but not a writer on the film, has no such doubts.

"I am totally thrilled with the film," he says. "I think Lee Daniels who directed, Susan Laurie Daniels who wrote it and the entire cast did an incredible job, all the way through the process.

"I've been really struck by how deep their intelligence was, their moral commitment to the story, their desire to get it right – their desire to honour Billie Holiday and what was done to her."

He's also more than happy that the film means he's talking about the drug war again. Hari has several books on the go, including "in the super long-term", one about a renowned linguist and dissident intellectual. But he does not mind a bit being the drug reform guy.

"I'm unbelievably proud to be a small part of this incredible movement all over the world," he says. "It's so important, it's one of the simplest things we could do to save the largest number of lives and some of the most vulnerable people.

I'm unbelievably proud to be a small part of this incredible movement."

"Also, just on a personal level with drug policy reform, I've been involved in various political movements in my life and drug policy reform has the highest calibre of people, the lowest level of sectarian bullshit and posturing and the highest level of moral commitment and intelligence of any political movement I've ever been part of."

Which does raise the question of why the war on drugs is still with us. If there are these organisations full of ethical, intelligent people doing good work and championing the evidence – why don't things change faster?

"It's a range of reasons. Why does the drug war continue when it's such a disaster, when the evidence shows it increases the number of people with addictions and the number of people who die of drug-related causes and releases an enormous amount of prohibition-related terror across the world?

Given that we know all this, and given that the evidence for that is as clear as the evidence that human behaviour is driving global warning or that vaccines work? This is very clear evidence. Why is it not changing?

"Firstly, it is changing unbelievably quickly. The day Bill Clinton left office, 15% of Americans were in favour of legalising cannabis. Today, most Americans live in a state where cannabis is legal. The whole of Canada has legalised cannabis.

I've been to lots of places around the world, from Colorado to Canada to Uruguay that have fully legalised cannabis. There's been huge movement on other issues. In fact, at the very heart of the country that imposed the drug war on the world, Oregon has now decriminalised all drug possession. We're seeing a wave of reform all over the world.

Oregon's state legislature with politicians talking at their desks. - In a wave of drug reform around the world, Oregon has decriminalised all drug possession.

"But you're absolutely right. Given how harmful this policy is and given how overwhelming the evidence to the alternative is, it's very important to ask, why is change not happening faster? There's an obvious reason, which is true but somewhat overstated and when people like me talk about it, we put too much weight on it – that there are vested interests in favour of the drug war because they benefit from it."

Those vested interests, he says, include police and prison unions and "the alcohol lobby". And yet, while a majority of the public believes the current drug war has failed, "people have yet to be persuaded of the alternatives. So people don't think what we have at the moment is good, but they fear that what would come after reform would be even worse."

There are, he thinks, several "jobs to be done" that could bridge the gap.

"One is explaining to people what actually happens when you reform – and too often this is talked about as if we're at a philosophy seminar and we're talking about a kind of abstract proposal.

"There's nothing abstract about alternatives to the drug war. I've been to the places that have done it. I've been to Switzerland where they legalised heroin for people with addiction problems – and ended heroin overdoses in the legal market.

"I've been to Portugal where they decriminalised all drugs and went from having one of the worst drug problems in the world to having almost the lowest level of drug problems in the entire European Union.

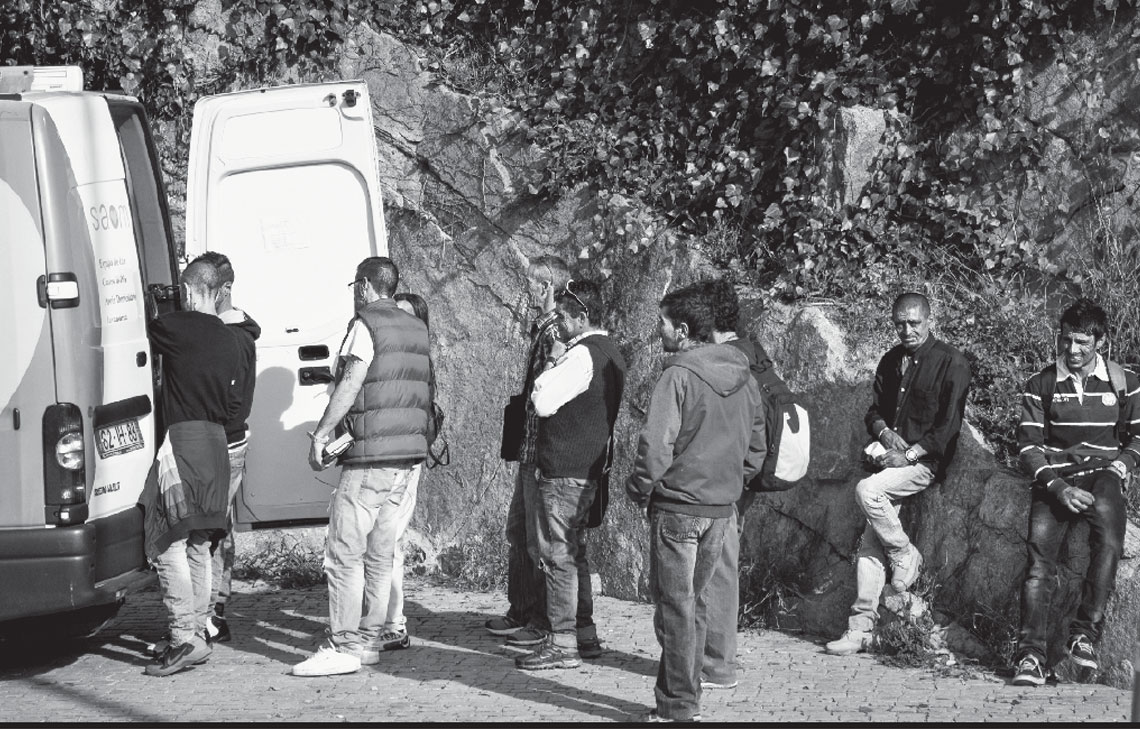

Mobile health workers in Portugal - Portugal has invested heavily in drug treatment and prevention. Photo credit: Neil Moralee, flickr

"It's important to explain to people what actually happens when you move to to decriminalisation or legalisation. We've seen the evidence that in Colorado, adolescent drug use fell after legalisation. Drug dealers don't check ID, licensed businesses do."

But local drug reform advocates learned in the course of last year's cannabis referendum campaign that simply shouting evidence at people has its limits. Hari believes drug reform needs the kind of movement that gradually made homosexual law reform, then marriage equality, tenable in many Western countries.

A part of the social shift behind that was the ability to see the issue on a human level: if two people love each other, why shouldn't they be able to be together? Will taking along the public on the road to drug reform need some of that?

"You're 100% right. One of the reasons why I wrote Chasing the Scream as the stories of people, the interconnected stories of lots of people at different moments in the drug war – from Billie Holiday to a trans crack dealer in Brooklyn, to a hitman for the deadliest Mexican drug cartel, to a homeless street addict in Vancouver who started an uprising there – is precisely that.

"There are very few people who can hear the story of Billie Holiday and think, I don't care if she lived or died."

It comes down, he believes, to three "moral principles". The first is that all people deserve to live and have good lives. The second is liberty: most drug use does not result in addiction or serious problems and there is no good reason to prevent the human pursuit of the "natural intoxication impulse", be it in a pub or somewhere less legal.

"The third moral issue is for me the biggest – the violence caused by prohibition, which is even bigger than addiction. Imagine that you go into a shop now and steal a bottle of vodka. The shop will catch you, they'll call the police, the police will come and take you away.

"The people who run that store don't need to be violent, they don't need to be intimidating, they've got the power of the law to uphold their property rights.

"Now imagine you want to steal a bag of cannabis or a bag of cocaine. If you did that, obviously the people who own it can't call the police – the police would come and arrest them! They have to fight you.

"But also, they don't want to be having a fight every day, so they have to establish a reputation for being so frightening that no one would be so foolish as to screw with them.

"So the war on drug creates a war for drugs. As [American journalist and early critic of the drug war at America's southern border] Charles Bowden said, to operate in a prohibited market, people who sell drugs have to be violent and intimidating.

"And if you want to know how much is due to prohibition rather than due to the drug itself, just ask yourself – where are all the violent alcohol dealers?"

People who sell drugs have to be violent and intimidating. ... just ask yourself – where are all the violent alcohol dealers?"

Hari is encouraged by the apparent shift in the rationale for cannabis reform in the US to a social equity framework ("The idea that when you legalise, the communities that have been most devastated by the drug war should be the first in line to benefit from the legalisation, I think that's really important") but also believes there are multiple valid motives for reform.

"The thing about the drug war is that it's such a bad policy that you can come from so many different perspectives and be in favour of ending it. Some of the people I most admired who I met were people with very different politics to me.

"You can be a conservative authoritarian who just doesn't like violent criminals and that can be your reason to want to end the drug war. You can be an economic libertarian who doesn't like the wasting of tax money. That can be your reason. You can be a social justice anti-racist who doesn't like the grossly racist outcomes of the drug war – and the grossly racist way it has always and will always be fought.

"That can be your reason to do it. One of the things I find exciting about this is that it's not a left-right issue."

Hari confesses to being "frustrated" by the result of New Zealand's cannabis referendum, both because "any break in the chain inspires other breaks in the chain" globally and because the referendum debate became needlessly politically polarised.

He hopes the issue can be revisited soon. On the other hand, he's delighted that our government delivered on a promise to legalise festival drug-checking ahead of the summer season – the more so after hearing about the way the dangerous cathinone eutylone flooded the party drug market during the summer.

Everyone in New Zealand should be really proud that ... you've made the choice to protect the lives of your young people."

"Everyone in New Zealand should be really proud that together as a country you've made the choice to protect the lives of your young people – and not needlessly surrender them in the name of an ideological cause.

"It's exactly like having seatbelts in cars. When seatbelts were introduced, some people said we shouldn't have seatbelts because it'll make people reckless, it'll make them drive faster. Now, no one says that.

"Every time there is pill-testing, they discover some pills that are contaminated – because, by the way, they're supplied by criminals in a system of prohibition, no one's buying poisoned alcohol in NZ. But given that we have prohibition, do you want to maximise safety, or do you want people to unnecessarily die?

"There would have been several people who died at music festivals this year in New Zealand and they're alive and they will go on to have good lives – because this sensible policy was introduced.

"And we should build on that and introduce other policies that save people's lives."

A message to our supporters from Johann Hari

Recent news

Reflections from the 2024 UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs

Executive Director Sarah Helm reflects on this year's global drug conference

What can we learn from Australia’s free naloxone scheme?

As harm reduction advocates in Aotearoa push for better naloxone access, we look for lessons across the ditch.

A new approach to reporting on drug data

We've launched a new tool to help you find the latest drug data and changed how we report throughout the year.