Reducing cannabis health harms

There is a wide spectrum of views on how much (or, in some cases, even whether) cannabis causes harm. The divergence of views is backed up by widely varying research, and it’s not hard for either cannabis proponents or opponents to find a good selection of studies supporting their view. Rob Zorn examines how harmful cannabis can really be and what can be done to reduce those harms.

Cannabis has a very low acute toxicity. In other words, you’d have to ingest massive amounts of the stuff to overdose. Because of this, it’s very hard to find any evidence of anyone dying as a direct result of taking it. Nevertheless, there is enough research to indicate that, when used in certain ways or by certain people, cannabis is associated with a variety of health and other harms, especially amongst regular long-term users.

There can be short-term negative psychological effects such as anxiety and paranoia, but these will usually pass; temporary psychomotor impairment that may get you (or someone else) killed if you get behind the wheel; disruption to your cognitive functions such as short-term memory loss and disruption to temporal processing and learning.

However, those with sustained use (daily or near daily over several years) expose themselves to much greater, long-term health risks.

There is solid evidence, for example, linking heavy use with respiratory disease. A succession of clinical studies show increased risk of chronic bronchitis, sore throat, inflammation, impaired immune function and pre-cancerous cell changes. There is also evidence linking prolonged cannabis use with increased risk of mental illnesses such as schizophrenia, at least for those who may be predisposed.

Most people seem able to quit cannabis, even after years of use, with very little withdrawal, but others will become more chronically dependent. The commonly accepted ratio is one in 10 cannabis users who are predisposed towards this, and that’s a lot of people considering the popularity of the drug.

There are a number of strategies and approaches aimed at reducing the harms associated with these adverse health outcomes, and they can involve a variety of media. The first challenge is getting the cannabis user to listen to harm reduction messages, and of course, there’s little research available so far about what works best.

NORML spokesperson Chris Fowlie suggests the best people to talk to cannabis users about reducing harm are cannabis users themselves. He would like to see harm-reduction education disseminated by trusted ‘peers’ in a similar way to needle exchanges. This could be information about the risks associated with excessive use or how to reduce respiratory harms through safer smoking techniques.

“The logical way to do this would be through head shops, but the current legal environment here makes this virtually impossible. Any information the shops start handing out about drug use puts their business at risk because it associates their ‘ornaments’ and ‘vases’ with cannabis smoking.”

NORML used to provide harm reduction material in every issue of its former publication NORML News. But other than word of mouth, there is not much in the public domain, unless you want to start engaging with treatment.

But even if we could find the perfect medium, what would our messages be?

The most obvious advice to avoid cannabis harm is not to smoke cannabis. This is especially important if you’re predisposed to psychosis or you have experienced negative psychotic effects when due to cannabis. But most people who smoke cannabis are not, and many just want to minimise the risks. And we should also not underestimate the benefits of cannabis, such as relaxation, which are powerful motivators for continued use. Some see their cannabis use as a form of harm reduction in itself because it creates fewer problems for them than other drugs like alcohol.

Knowledge is about the best weapon we have in the arsenal. It doesn’t ensure behaviour change, but it does mean people are better able to make informed decisions about whether their use is becoming a problem and how they can use more safely. Not combining it with alcohol or tobacco, not driving high, the possibility of dependence and where to get help might form the core messages.

These are all important but will affect only some users. Something that’s relevant to just about all cannabis users is respiratory harm. This is interesting and significant because myths abound about what constitutes safe smoking, and a number of new technologies are emerging that may reduce respiratory harm.

Most people would think (and it would seem to make sense) that smoking a filtered joint or a water bong would be easier on the lungs than smoking an unfiltered joint, but actually quite the opposite is true, and it all has to do with tar to THC ratios. The problem is THC molecules are ‘sticky’ and tend to adhere to other molecules such as those of the tar and particulates you’re filtering out. The end result of this is that you have to smoke more to get as high, and you actually ingest more tar per amount of THC.

Bongs can also harbour infectious germs if they’re not cleaned regularly (bacteria love a warm, moist environment), and bongs home-made out of plastic bottles are especially disastrous because of the extra toxins you can inhale from the heated plastic. If you are going to use a bong, make sure it’s a good one, preferably made of glass.

Meanwhile, vaporisers look like a promising alternative. A ‘vape’ heats the cannabis to a temperature high enough to release psychoactive cannabinoids but not high enough for combustion to occur, which is when most of the tar and other nasties are released.

A 2001 study led by Dale Gieringer of NORML California compared all four smoking methods (bongs, vaporisers and filtered/unfiltered joints and found only vaporisers improved the ratio of tars to cannabinoids. The filtered joints performed worse than the unfiltered joints (30 percent more tar per cannabinoids), and the bongs performed worst of all (up to 180 percent more tar).

Vaporisers have improved since 2001 and are now less bulky, but they can be difficult to find in New Zealand.

“Customs doesn’t tend to like them, and it can be very difficult to get them into the country, making them rare and expensive,” Fowlie says.

Many cannabis smokers here would probably use them if they were more cheaply and readily available. An Addiction Research and Theory study published in 2010 found using a vaporiser reduced the respiratory symptoms of all four participants in the study. Participants were asked to return to normal smoking for a month after 30 days of using only a vaporiser but were informed this was not a requirement of the research. All four participants refused and preferred to continue with the vaporiser. So though the high from a vaporiser takes longer (several minutes to peak as opposed to two minutes for smoked cannabis), it seems the effects are acceptably close to those of a combustible high.

Of course, another alternative is not to smoke the cannabis at all but to eat or drink it instead. Drinking cannabis in tea or eating it in cookies and cupcakes has been around for a long time but has not been all that widespread because the effects take longer with oral ingestion (up to an hour or more) and can be less predictable. But that may be about to change.

Fowlie recently attended the first World Cannabis Week (like a cannabis-themed trade show) in Colorado and says he was amazed at the amount of edible cannabis products available. These range from confectionery to THC-infused drinks to some sort of gaseous concoction that was “pretty amazing but hard to describe”.

“All the products had accurate content descriptions based on clinical research. There was a chocolate bar, for example, and the label told you how many and what sort of cannabinoids each square of chocolate contained. This is what can be achieved under a legally regulated system. You know exactly what you’re getting, and it’s much easier to titrate [regulate your own dose] in that situation.”

In Colorado, he says, there are up to 200 companies making edible products. And while these were originally mostly for medical cannabis users, they are becoming more popular with recreational users as there’s a growing demand for non-smoked alternatives.

There were also e-cigarettes available that deliver a standardised dose in terms of strain and potency. These might be ideal for those not yet ready to forsake smoking cannabis. E-cigarettes that deliver cannabinoids can still be passed around as part of sharing the ritual with your ‘fellow outlaw’ and mimic the pleasures of smoking cannabis in the same way they mimic the pleasures of tobacco smoking.

All well and good – but what do we do about chronic users who want to stop because cannabis is causing them harm but for whom withdrawal is now an issue?

Symptoms can include craving, irritability, insomnia, headaches and shakiness, and we should definitely see withdrawal as a harm, says David Allsop of the National Cannabis Prevention and Information Centre at the University of New South Wales.

“It increases demand on treatment providers and drives users back to a drug they don’t want to take any more.”

New Zealand treatment relies mainly on hybrids of motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioural therapy to manage withdrawal and help cannabis users who want to stop.

“It’s about getting them through those first couple of weeks of sleeplessness, craving and irritability,” says Ben Birks Ang of Odyssey House New Zealand.

“Helping with sleep is a big one, especially for teenagers who don’t tend to get a lot of sleep anyway and who used to rely on cannabis to nod off. While motivation is important, a lot of young people haven’t had the years of use to notice a build-up of harm. So with some young people, we work on building motivation and other protective factors, like their relationship with their family or school, so when they are ready to change, the foundations are set.”

Other countries are beginning to explore supplementing counselling with more pharmacologically based cannabinoid replacement therapies that would work similarly to methadone for opioid users. Sativex, a cannabis-based drug originally developed in the UK to treat the pain and symptoms of multiple sclerosis (MS), seems especially worth a look.

A recent University of New South Wales study found Sativex significantly reduced the overall severity of cannabis withdrawal symptoms and – always a good sign – that participants given the drug remained in treatment longer.

“What might give Sativex the edge,” Allsop explains, “is that it’s cannabis-based and much closer to what people were actually using. It’s administered as an oral spray, so it’s more akin to smoke, and has a more rapid impact because it doesn’t have to be digested.”

The ‘good’ cannabis harm-reduction arsenal of New Zealand’s future will surely include cannabinoid replacement therapy, but right now, withdrawal sufferers should not be holding their breath. Sativex is a Class B drug in New Zealand and currently only approved for MS sufferers who have not responded to other treatments. It is not funded by PHARMAC, and ministerial approval must be gained before it can be prescribed at all.

But perhaps the first thing we should do is consider treating cannabis use as a health issue instead of a legal one so we can have more open dialogue with cannabis users who don’t fear being treated like criminals. What’s happening overseas seems to indicate this isn’t anywhere near as scary as we once might have thought.

Reducing respiratory harms from smoking cannabis

From the Drugs Meter developed by Dr Adam R Winstock, Consultant Addiction Psychiatrist and Addiction Medicine Specialist, South London, and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust

- Don’t mix cannabis with tobacco.

- Don’t inhale too deeply or hold smoke in the lungs. This doesn’t get you more stoned but increases tar and carcinogen contact.

- Remove stalks, leaves etc.

- Don’t use a cigarette filter. Filters just reduce the cannabis/tar ratio.

- Don’t use too many papers.

- Clean bongs/pipes thoroughly.

- Don’t use plastic bottles/pipes as these can increase toxic fumes.

- Use a vaporiser.

Access the Drugs Meter and assess your personal drug use at www.drugsmeter.com

See also nzdrug.org/normladvice

Rob Zorn is a Wellington-based writer.

Recent news

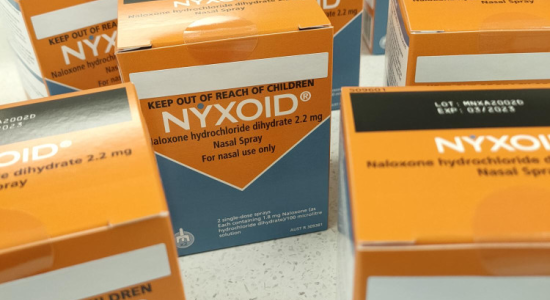

Expert Pharmac committee recommends funding for overdose reversal nasal spray

Public funding for a lifesaving opioid overdose reversal nasal spray is one step closer, with an expert committee saying that funding the medicine for use by non-paramedic first responders and people at high risk of an opioid overdose is a

Reflections from the 2024 UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs

Executive Director Sarah Helm reflects on this year's global drug conference

What can we learn from Australia’s free naloxone scheme?

As harm reduction advocates in Aotearoa push for better naloxone access, we look for lessons across the ditch.